JMS Pearce

Hull, England

Among the remedies which it has pleased almighty God to give to man to relieve his sufferings, none is so universal and so efficacious as opium.

– Thomas Sydenham, 1680

The controversial pharmaceutical company Farbenfabriken Bayer AG* had an important role in the development of morphine, heroin, and aspirin, the most effective and widely used pain-relieving drugs.

Opium

Opium is a crude extract from the milky latex of the annual poppy Papaver somniferum whose powerful narcotic effects were known and used by Theophrastus (373–287 BC) and later by Dioscorides (AD c. 40–c. 90). In the Odyssey Book 4, Homer mentions a drug νηπενθές (nepenthe: thought to have contained cannabis or opium), which Helen gave to Telemachus and his comrade:

Then Helen, daughter of Zeus, took other counsel. Straightway she cast into the wine of which they were drinking a drug [nēpenthés phármakon] to quiet all pain and strife, and bring forgetfulness of every ill.

Celsus (AD 14–37) in De Medicina advised opium analgesia to lessen the pain of surgery. Opium was used throughout ancient Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, Persia, and India.1

Osler described opium as “God’s own medicine.” It was long established for relief of many sources of pain, notably by Thomas Sydenham (1624–1689) who used laudanum (tincture of opium) for dysentery and pain relief. It was used for postoperative pain relief in the eighteenth century by surgeons Benjamin Bell and James Moore.

Morphine and heroin

Morphine

Friedrich Wilhelm Adam Sertürner, born near Paderborn, Germany in 1783, was a pharmacist’s assistant who around 1805 first isolated a narcotic substance from the milky exudate of the seed capsule of the poppy, Papaver somniferum.2 He first named it “principium somniferum” and later “morphium” after Ovid’s name for the god of dreams, the son of Somnus (Sleep). The poppy contains many alkaloids, including morphine, codeine, thebaine, and papaverine. Morphine was the first plant alkaloid isolated, but eventually, many opium alkaloids were synthesized and used as analgesics.3 Not until the development of the hypodermic needle and syringe by Alexander Wood in I853 was morphine given systemically by injection.

Heroin (diacetylmorphine)†

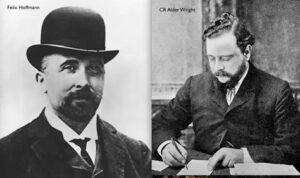

Felix Hoffmann (1868–1946) and Heinrich Dreser, both chemists at Bayer Laboratories, are often credited with the synthesis of diacetylmorphine (heroin) by a process of morphine acetylation. Priority for its synthesis, however, does not rest with Hoffmann and Bayer.

Diacetylmorphine had already been synthesized by C.R. Wright in 1874 (vide infra).4 The Bayer Company commercialized it, and the use of Heroin as its name was registered as a trademark in 1898. The name reflected the German word heroisch referring to the mythological Hero, a priestess of the goddess Aphrodite. Dreser published his paper on heroin and other morphine derivatives in Archiv für die gesammte Physiologie des Menschen und der Thiere in the same year.

The 1898 patent recorded its use as a sedative, and The Lancet of that year described it as a hypnotic. It was a useful cough suppressant, more effective than codeine (C18H21NO3 methylmoprphine) but considered not to be addictive. In 1898 at the Congress of German Naturalists and Physicians, Dreser claimed that heroin was ten times as effective as codeine in the treatment of respiratory diseases; he inaccurately estimated that it had only one-tenth of the toxic effects.5 In 1906, the American Medical Association approved Heroin for general use in place of morphine. When its addictive properties were realized5 Bayer stopped its production in 1913.

Heroin is three to five times more potent than morphine. Similar to the natural neurotransmitter endorphins—the analgesics produced in response to stress or pain—morphine and diacetylmorphine, being highly lipophilic, easily cross the blood-brain barrier to act on opiate receptors. Morphine and opiates are now known as phenanthrene alkaloids acting as agonists at mu, kappa, and delta opioid receptors,6 distributed throughout the central and peripheral nervous systems.

Although not initially regarded as addictive, the common experiences of euphoria and ecstasy quickly became apparent, particularly with intravenous use, causing addiction and recreational abuse, despite only partly effective legal restrictions.

Charles Romley Alder Wright FCS, FRS (1844–1894)

|

| Fig 1. Felix Hoffmann & CR Alder Wright. |

Twenty-three years before Bayer marketed heroin, Charles Alder Wright of St. Mary’s and St. Bartholomew’s Hospitals synthesized diacetylmorphine (C21H23NO5 heroin) in 1874. (Fig 1)

With his colleague FM Pierce, seeking a drug less addictive than morphine, he boiled anhydrous morphine alkaloid with acetic anhydride and produced a more potent, acetylated form of morphine he called “Tetra-acetylmorphine,” or more correctly, diacetylmorphine.4 Though powerful as an analgesic, Wright recognized its addictive properties and ceased further studies. There was sparse medical interest in diacetylmorphine until Hoffmann and Heinrich Dreser at Bayer Laboratories marketed it as Heroin in 1898. The complications of opiate addiction, abuse, and their dire social effects were soon to become well known.

Wright was born in Southend, Essex and trained at Owens College Manchester.7 During 1866–67, he worked as a chemist at the Runcorn Soap and Alkali Co. Cheshire. In 1867 he came to London as an assistant, first to Dr. A. Bernay of St. Thomas’ Hospital, and subsequently to Dr. A. Matthiesen of St. Mary’s and St. Bartholomew’s Hospitals, with whom he published many scientific articles. His prolific and diverse research included investigations of the metallurgy of iron, aluminum, and various alloys; the manufacture of alkali and soap; and the preparation of waterproof paper and canvas goods.

He graduated B.Sc. in 1865 and D.Sc. London in 1870.7 During this time he published his research on diamorphine, alkali manufacturing, and on iron smelting. He was a founder of the Royal Institute of Chemistry and in 1881 was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS). He was an examiner for the University of Durham, the Royal College of Physicians, and the City and Guilds of London.

Aspirin

Interestingly, Felix Hoffmann is also linked to the preparation of acetylsalicylic acid to replace salicylic acid on August 10, 1897. Bayer marketed it as Aspirin in 1899 and in 2022 continued to give8 Hoffmann and Dreser credit:

Aspirin®, which was developed by Felix Hoffmann and launched onto the market in 1899.

Arthur Eichengrün, who also worked at Bayer, later revealed10 that Dreser had not recognized its therapeutic potential and discarded it for nearly eighteen months. Acetylsalicylic acid was synthesized under Eichengrün’s direction‡ and without him the drug would not have been introduced. Indeed, at a management meeting it was Eichengrün who called for clinical studies to be initiated, but Dreser used his right of veto.8 Convinced of the potential of acetylsalicylic acid, Eichengrün tested it on himself, experiencing no ill effects. He surreptitiously gave a supply of it to his colleague Dr. Felix Goldmann, who then recruited physicians to evaluate the drug with encouraging results.

Although synthetic opioids were later developed, morphine was and remains the most valued means of alleviating pain. The problems of opiate addiction, abuse, and illicit trading were soon recognized worldwide. In 1914, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Harrison Narcotic Act that declared narcotic use illegal except for medical purposes. Heroin was placed under international control of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. In the United Kingdom, diamorphine can be provided under the management of a physician with listed precaution about dependence and addiction.

With the frailties of human nature, abuses of opium were inevitable. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the trade in Chinese tea, silks, and porcelain was extremely lucrative for British merchants. The East India Company smuggled Indian opium into China, for which they demanded payment in silver, which was then used to buy tea and other goods. The Opium War (or First China War) was partly a trade dispute between the British and the Chinese Qing Dynasty. By 1839, opium sales to China paid for the entire tea trade. During the next three years, there were several naval skirmishes and British invasions. A truce was reached in August 1842 with the Treaty of Nanking, in which China paid the British an indemnity, ceded Hong Kong, agreed to a reasonable fair tariff, and permitted trade at treaty ports, including Canton and Shanghai. Further trading disputes led to a Second Opium War in the 1850s until Britain, France, The United States, and Russia signed treaties with China at Tianjin in 1858 and Beijing in 1860.

In literature

|

|

| Fig 2. ST Coleridge. The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Pogány’s illustrated edition, 1910. Source | Fig 3. Thomas De Quincey. Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. 1822. Source |

Poets and writers through the ages have described the oblivion and appeasement of sufferings of body and mind afforded by the poppy. Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Dickens’s friend, the writer Wilkie Collins, were well known laudanum addicts. John Keats in Endymion wrote: “Through the dancing poppies stole A breeze, most softly lulling to my soul.”

But they also warn of dangers. “Who is the man who can take his leave of the realms of opium?” asked the French poet Charles Baudelaire. Oscar Wilde in Dorian Gray tells how: “There were opium-dens, where one could buy oblivion, dens of horror where the memory of old sins could be destroyed by the madness of sins that were new.”

Coleridge’s “bondage of opium” probably inspired the wonderfully imaginative ideation of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798) (Fig 2), but it destroyed his life and his kinship with Wordsworth.10,11

Thomas de Quincey publicized his addiction in the notorious Confessions of an English Opium Eater (1822). His use of the drug defied medical advice, but he recognized its dangers: “Indeed, the fascinating powers of opium are admitted even by medical writers, who are its greatest enemies.” “Nobody,” he says candidly, “will laugh long who deals much with opium: its pleasures even are of a grave and solemn complexion.”

Sadly, despite legislation, worldwide drug trading, recreational abuse, and addiction continue.

Notes

* From Wikipedia: “In 1925 Bayer merged with five other German companies to form IG Farben. Following World War II, the Allied Control Council seized IG Farben’s assets because of its role in the Nazi war effort and involvement in the Holocaust including using slave labor from concentration camps and humans for dangerous medical testing, and production of Zyklon B, used in gas chambers. In 1951…Bayer was reincorporated as Farbenfabriken Bayer AG.”

Wikipedia further records that Fritz ter Meer, Bayer chairman, was sentenced to seven years in prison in 1948 during the Nuremberg Trials for “plunder and spoliation” and for “mass murder and enslavement.” After release in 1951, he was selected as chairman of the board of directors for Bayer AG.

† Also called by addicts and traders dynamite, H, horse, junk, scag, or smack.

‡ Sneader records that Eichengrün did not boast of his prime role in the discovery until 1944, while incarcerated in Theresienstadt concentration camp he described events in a letter to Bayer (in the Bayer archives).8

References

- Hamarneh S. Pharmacy in medieval Islam and the history of drug addiction. Med Hist. 1972;16(3):226-37.

- Sertürner FW. Ueber das Morphium, eine neue salz– fahige Grundlage, und die Mekonsaure, als Hauptbestandtheile des Opiums. Gilbert’s Annalen der Physik 1817;55:56-89.

- Macht DI. The history of opium and some of its preparations and alkaloids. JAMA 1915;64(6):477-81.

- Wright CRA. On the action of organic acids and their anhydrides on the natural alkaloids. Part I. J Chem. Soc. 1874;27:1031-43.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. History of Heroin 1953:3-16. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/bulletin/bulletin_1953-01-01_2_page004.html.

- Devereaux AL, Mercer SL, Cunningham CW. DARK Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: Morphine. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2018;17;9(10):2395-407.

- Charles Romley Alder Wright. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Romley_Alder_Wright.

- Sneader W. The discovery of aspirin: a reappraisal. BMJ 2000;321:1591-4.

- Eichengrün A. 50 Jahre Aspirin. Pharmazie 1949;4:582-4.

- Lefebure M. Samuel Taylor Coleridge: A bondage of opium. London: Gollancz, 1974.

- Pearce JMS. Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s bondage of opium. Hektoen International Journal Spring 2022.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.

Spring 2023 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply