Srilakshmi Chidambaram

Manila, Philippines

|

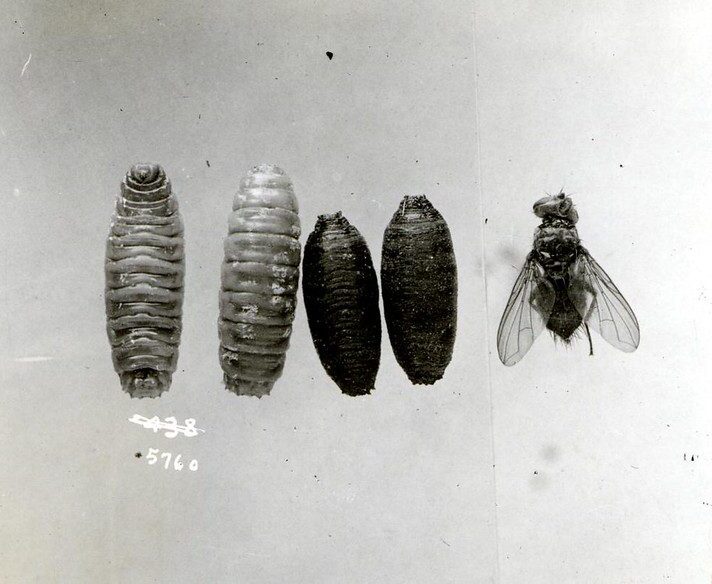

| Transformation of large cone maggot from larvae to adult. USDA Forest Service via Flickr. |

Picture the scene: A body, blue with bloat, sprawled across the floor. The skin is sloughed off and peeling; fat drips through the carpet. The room is warm with the sickly-sweet stench of decay. A living, seething mass of flesh-eating maggots swarms the body. Blowflies. Your boot touches a hardened pupa casing.

Stifle the urge to squirm and think of the larger picture. Insects have been associated with the deceased for millennia. In AD 1247, Sung Tz’u authored The Washing Away of Wrongs, a pioneering forensic manual which described how flies are attracted to the scent of blood, even in trace quantities. This work is one of the oldest documented evidences of insects being used for judicial procedures.1

Though other scientists were aware of the curious relationship between corpse and insect, it was not until the late 19th century that the idea became a popular one. This was largely due to the efforts of French veterinarian Jean Megnin, who published Fauna of Tombs and Fauna of Corpses, revolutionary texts in forensic entomology.1

In 1898, Murray Motter examined 150 disinterred remains that had been exhumed for the relocation of a cemetery. He observed that a wide variety of insects inhabited the bodies at different developmental stages, and he accordingly published these results in the Journal of the New York Entomological Society.2

Though the paper did not gain much traction, it spurred entomologist H.B. Reed to consider how a corpse influences the environment in which it decomposes, an ecosystem known as the necrobiome. He observed the insects that flocked to a series of dog carcasses over a one-year period and found that their numbers were greater in the warmer months, though a few individual species peaked reproductively independent of the weather.3

In 1965, Jerry A. Payne published his watershed paper on a carrion study of a baby pig in the journal Ecology. His experiments revealed a definitive range of ecological succession in the fauna of a necrobiome, each taphonomic stage defined by a particular niche of arthropod. He went on to conduct many more studies on decomposing pig carcasses, eventually coming to list more than 500 species of insects associated with decay.4

Though these observations were intriguing, a study of the same scope had yet to be done in humans. This changed with the establishment of the Body Farm in 1981, a research institute for forensic anthropology at the University of Tennessee. Under the guidance of director William Bass, Bill Rodriguez undertook seminal research on insect species that colonized human corpses.1

What he observed was this: the first insects found on fresh bodies were blowflies, mostly bluebottles and greenbottles. These are large bristly flies with iridescent coloring on their abdomens that possess an uncanny sense of smell for decaying flesh. They usually lay eggs in daylight, preferring damp orifices such as the eyes, lips, mouth, and groin. Some even oviposit in the living (a phenomenon known as myiasis).5

Upon hatching, blowfly maggots penetrate the body’s soft tissues with the aid of powerful proteolytic enzymes. They feed in a teeming crowd known as a maggot mass, generating vast amounts of heat in the process. After their final moult, they migrate into a dark space nearby to pupate and metamorphose into adults. The entire process is well defined and takes around twelve days to complete, accelerated by warm ambient temperatures.5

The end of the body’s moist putrefaction stage is associated with other kinds of insects. Houseflies (Musca domestica) tend to prefer well decomposed flesh over fresh specimens. Cheese flies and coffin flies are usually next to arrive, followed by dermestid beetles three to six months after death. These beetles clear up whatever remains of dried and adipocerous corpses and are so efficient at their work that they used by museums to prepare taxidermy specimens. House moths finish off the job by working at hair and mummified tissue.5

Insect life demarcates each stage of the body, from fresh to bloat to disintegration. Forensic entomologists interpret their presence to establish post-mortem intervals in death investigation, as well as in abuse cases, detection of certain drugs, and incidents of stored-product contamination.

This niche field allied to forensic medicine has advanced in recent years with the incorporation of many modern techniques. Scanning electron microscopy and KMnO4 staining can help distinguish morphological features in insect eggs. Mitochondrial DNA differentiates between species in the same family. Developmental stages can now be further classified based on changes in gene expression, allowing for improvements in accuracy.

So, the next time you see a maggot or a bluebottle, shake off your instinctive revulsion. Think of the importance they serve as evidence in the law courts, determining the scales of justice, acting as a voice for the deceased and sentencing the condemned. Hopefully, there will be no corpses nearby.

References

- Bass, Bill and Jon Jefferson. Death’s Acre: Inside the legendary forensic lab the body farm where the dead do tell tales. New York: Berkley Books, 2004.

- Motter, Murray. “A Contribution to the Study of the Fauna of the Grave. A Study of on Hundred and Fifty Disinterments, with Some Additional Experimental Observations.” Journal of the New York Entomological Society 6, no. 4 (1898): 201-31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25002830.

- Reed, H.B. “A Study of Dog Carcass Communities in Tennessee, with Special Reference to the Insects.” The American Midland Naturalist 59, no. 1 (1958): 213-45. https://doi.org/10.2307/2422385.

- Payne, Jerry. “A Summer Carrion Study of the Baby Pig Sus Scrofa Linnaeus.” Ecology 46, no. 5 (1965): 592-602. https://doi.org/10.2307/1934999

- Knight, Bernard and Pekka Saukko. “The Pathophysiology of Death.” In Knight’s Forensic Pathology, 76-9. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2016.

SRILAKSHMI CHIDAMBARAM is a 20-year-old university student currently studying in the Philippines. She finished her pre-medical programme in psychology and statistics and recently started the second year of her MD. She aspires to work in the fields of pathology and public health and has been in love with microbes since performing her first gram stain.

Submitted for the 2022–23 Medical Student Essay Contest

Leave a Reply