Matthew Turner

McChord, Washington, United States

The icy November wind cut like a knife through his dress uniform, down to his very bones, but the young doctor did not move a muscle. Like a statue, he stared ahead with the other men in the column at the podium before them. There was a speaker up there, giving a speech on patriotism and loyalty, but the young doctor did not hear a word. His heart pounded in his ears like a drum. Five years working on his MD and PhD, three months of basic training, even more time spent working his way up the ranks of the Institute—but finally he was where he was meant to be. He was finally ready to protect the people, defend the culture, serve the nation—and even now, he could see that his grateful country would grant him the prestige and opportunities that he had always dreamed of. A bright future was blooming ahead. And to think that he had once wanted to be a dentist!

The speech concluded, the speaker at the podium took a step back and suddenly snapped up his arm in a crisp salute. “Heil Hitler!” he shouted.

As one, a thousand men returned the salute. “HEIL HITLER!”

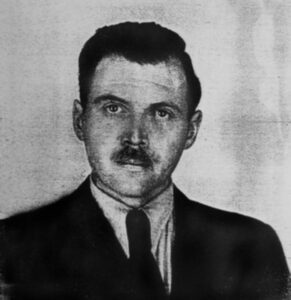

Dr. Josef Mengele, age twenty-seven, shouted as loudly as the rest of them. The year was 1938, and the ambitious young physician had just joined the ranks of the Nazi SS. The Angel of Death’s career was just beginning.

While Dr. Mengele—the infamous “Angel of Death” of Auschwitz1—remains the most infamous of the Nazi physicians, he was far from the only one. “Only a good person can be a good physician,” claimed Rudolf Ramm, the leading Nazi medical ethicist, in 1942.2 By that year, over 38,000 doctors—half of all German physicians—had joined the ranks of the Nazi party.2 Even before Hitler seized power, the Nazi cause was disturbingly appealing to doctors—from 1929 to 1933, the National Socialist Physicians’ League swiftly grew to include 3,000 doctors, 6% of the entire country’s physician workforce.2 Doctors like young Josef Mengele were seven times more likely to join the SS than other male professions.2 Fueled by unscientific theories of “racial hygiene” and a fixation upon ensuring the health of the “German people,” German physicians were an integral part in the Holocaust and numerous other Nazi atrocities.3 Other examples of physicians participating in human rights abuses can be found across history, including the American Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment,4 Imperial Japan’s Unit 731, South African apartheid, Soviet psychiatry, and countless examples of medical torture.5

The lesson is clear: physicians are positioned to cause unspeakable atrocities in the hands of destructive ideologies. Education alone is not an effective vaccine against fascism: at the time of the Nazis’ ascent to power, the German medical system was “exceptionally advanced” with an educational system that was the “model system for the world.”6 Germany even had regulations for human experimentation and informed consent as early as 1900, following an experiment that may sound uncomfortably familiar to American physicians—in which marginalized groups were deliberately infected with syphilis in an 1892 experiment.6 The Nazis never bothered to repeal these regulations. They simply ignored them.6 Laws only make a difference when there is someone who will enforce them.

This becomes even more concerning when one considers the rising levels of political polarization in the United States. Given this, the American medical establishment must not let itself be infected with hateful ideologies the way the German medical establishment was. So how can we do this? How can we keep the next Josef Mengele from rising in the United States? Like most difficult questions in medicine, there are many strategies that we can employ. However, the most effective change would be a bottom-up approach, a cultural shift within the ranks of physicians. Just as many German physicians were primed to accept fascism and the atrocities it brought,3 American physicians need to forge a culture that firmly rejects political extremism. There will always be men like Josef Mengele in the world. It is our duty to ensure that they never find an environment in which they can flourish.

References

- Curran WJ. The forensic investigation of the death of Josef Mengele. New England Journal of Medicine Oct 23, 1986;315(17):1071-3.

- Utley GJ, editor. The Nazi doctors and the Nuremberg Code: human rights in human experimentation: human rights in human experimentation. Oxford University Press, USA; May 7, 1992.

- Ernst E. Commentary: The Third Reich—German physicians between resistance and participation. International Journal of Epidemiology Feb 1, 2001;30(1):37-42.

- Brandt AM. Racism and research: the case of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Hastings Center Report Dec 1, 1978:21-9.

- Bloche MG. Caretakers and collaborators. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics Jul 2001;10(3):275-84.

- Cohen Jr MM. Overview of German, Nazi, and holocaust medicine. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. Mar 1, 2010;152(3):687-707.

DR. MATTHEW TURNER is currently an intern at Madigan Army Medical Center. He has always been fascinated by the intersection of medicine and history, and the stories that can be found there.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this work are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Madigan Army Medical Center, or the US Government.

Leave a Reply