Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

“A strange story indeed, almost too good to be true.”1

Until the end of the nineteenth century, a cesarean section to deliver an infant was considered to be an operation with much risk and little success. In England, some physicians “doubted if a cesarean section was ever justified.”2 The first successful cesarean section in Europe in which both mother and child survived was performed in Padua in 1876 by Edouardo Porro. By 1882, this operation was done with increasing success in Germany.3

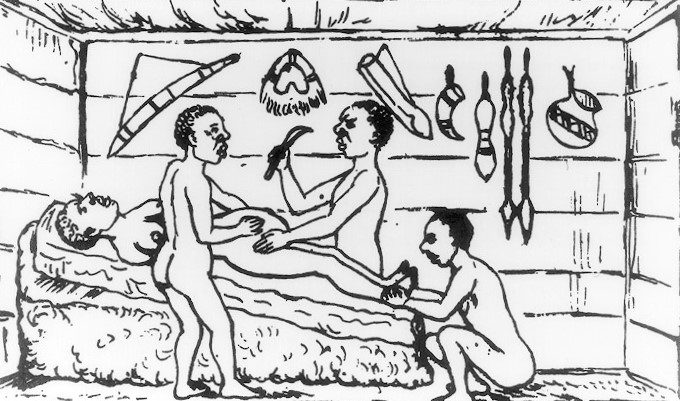

Robert Felkin (1853–1926) was in 1879 a Scottish medical student on a missionary expedition to Africa. There, he had the opportunity to observe a cesarean section done by a local healer in Uganda. The patient was a woman of about twenty and it was her first pregnancy. After a period of unsuccessful labor, her healer decided to resort to a cesarean section. The naked patient was fastened to a board by cloth strips around her chest and thighs. An assistant held her ankles. She was semi-conscious from the banana wine she was given to drink. The operator washed his hands and the patient’s abdomen with wine and made a midline vertical incision that began “just below the umbilicus.” This incision cut through the abdominal wall and partway through the uterine wall. Bleeding vessels in the abdominal incision’s edges were cauterized with a red-hot iron. The incision in the uterine wall was deepened, an assistant separated the incision’s edges, the infant was taken out, and the cord was cut. No sutures were placed in the uterus. The abdominal incision was closed with seven thin iron pins and fastened with string. A paste made of two different roots was applied to the wound, and a dressing was placed.4 Some pins were removed on the third post-operative day, and the rest by the sixth day. There were no signs of any systemic infection.5 By the eleventh day, the wound was healed completely.6

Felkin wrote that Uganda was the only country in Central Africa where an “abdominal section” was being done. There, it was a well-established procedure, not a rarity.7 Medicine in the Bunyoro Kingdom, where Felkin observed this surgery, was more advanced than in other sub-Saharan cultures, and in this respect more advanced than Western medicine. The doctors of the isolated Bunyoro Kingdom did not learn this surgical technique from outsiders. The first foreigners they met, in 1852, came from Zanzibar, and the first Europeans (Englishmen), in 1862.8,9 In 1877, Joseph Lister moved to London to “spread his gospel of antisepsis,”10 and in 1879 there was “still widespread scepticism about the practices of antisepsis and asepsis” in Europe and North America.11

Felkin was never thought to be a “hoaxer.”12 He had described a surgical procedure involving anesthesia (banana wine), asepsis (hand washing), hemostasis (a hot iron), and wound care.13 It was more than many of his British colleagues would believe.14

References

- Jack Davies. “The development of ‘scientific’ medicine in the African kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara,” Medical History, 3(1), 1959.

- Davies, “Scientific.”

- Caroline deCosta. “Banana wine and cross dressing,” O&G Magazine, 15(2), 2013.

- Robert Felkin. “Notes on labour in Central Africa,” Edinburgh Med Journ, 29(10), 1884.

- Sylvain Diop. “Overview of surgical and anaesthesia practice in sub-Saharan Africa during the 19th century: The example of the people of Bunyoro,” Pan African Medical Journal, 40(120), 2021. https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/40/120/full/.

- Felkin, “Notes.”

- Bo Lindberg. “Kejsarsnitt I myt och bild,” Svensk Medicinhistorisk Tidskrift, 26(1), 2022.

- Diop, “Overview.”

- deCosta, “Banana wine.”

- Davies, “Scientific.”

- deCosta, “Banana wine.”

- Davies, “Scientific.”

- Diop, “Overview.”

- Dr. Y. “Quick note on successful C-section Pre-Colonial Africa, in Bunyoro kingdom,” African Heritage, August 18 and August 23, 2021. afrolegends.com.

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Leave a Reply