Luisa Alanís Sáenz

Mexico City, Mexico

|

|

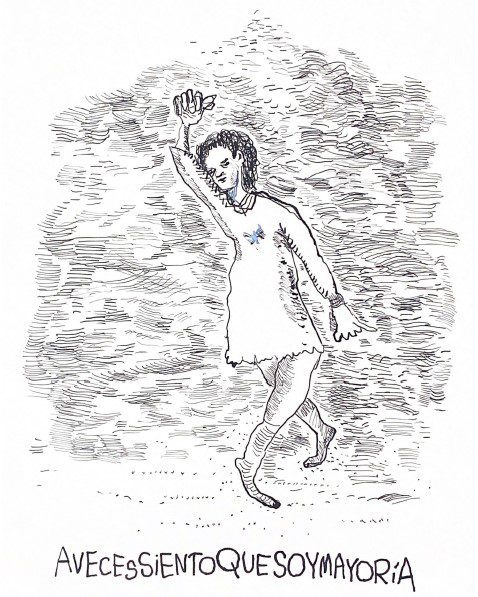

A veces siento que soy mayoría (Sometimes I feel like I am the majority). Artwork by Diane Wilke. Used with permission. |

“Shoot, they told me. I obeyed.

I’ve always been obedient. By obedience

I conquered my high rank

…

I’m not a good man or a bad man

I just follow orders”1

– José Emilio Pacheco (my translation)

In 1942, a man designed efficient plans to transport hundreds of thousands of people. Never meeting them, Adolf Eichmann ensured that they all boarded trains and were taken from point A to point B on time: a master of logistics. Those trains led to extermination camps, and hundreds of thousands of Jews were pushed into them.2

Decades later, Eichmann was tried. On the stand, he had one thing to say: “I just obeyed.” He had never thought about consequences. He did as he was told and was rewarded accordingly.

Fast forward seventy years. Amidst the nightly obstetric chaos in a northeastern Mexico hospital, a woman was about to give birth. After hours of pain, the head of the baby was almost out—everything progressing normally.

“Pass me the scissors,” my senior ordered.

I had learned that episiotomies (cutting the vaginal opening) should be done only if necessary.3 However, at this hospital, this was routine. I thought about challenging him, but I did not.

“Of course,” I answered as I gave him the scissors, aware of my participation in malpractice.

There were no complications—at least in the short term.

Going over this scenario in my head, I repeated, as reassurance, “She is going to be okay,” “It’s not that bad,” and “I just obeyed.”

Unfortunately, obeying for the sake of obeying is not uncommon in medical training. Questioning authority is not well received. Obedience—even blind—is often rewarded.

I am not comparing episiotomies to genocide but analyzing the symmetries between Eichmann’s logic and mine. I question a system which enables noncompliance to the detriment of safety. I ask: What pushed me into participating? What stopped me from speaking up? Is obedience necessary? To what extent?

We trainees like to feel like part of the team. After years of learning about diseases and bioethical principles such as beneficence, non-malfeasance and autonomy,4 we arrive at the hospital excited to put this knowledge into practice. But confronted by a dissonance between learnt ethics and a hidden etiquette, we comply with substandard care. We keep silent for fear of retaliation.5 We realize we must adapt to survive—even to being complicit. As stated by Andrew H. Brainard et al,6 “students become ‘professional’ and ‘ethical’ chameleons because it is the only way to navigate the minefield of an unprofessional medical school or hospital culture.”

Passing through moments of guilt, I discovered that others also feel this way.7,8 Auschwitz Ethics Fellow Sarah van der Lely discussed a classmate’s testimony in which their superior had requested a vaginal examination on an anesthetized woman without consent.9 Although all in their medical ethics class agreed the examination would be unethical, when asked who would refuse to do it, none spoke. We often learn that silently obeying is the smartest way to avoid conflicts and succeed.

In a field where many decisions mean life or death, structure is necessary. The person with the most knowledge and experience has the final say, and in emergencies, there is often no time for debate. But medicine is also tied to ethics. How can obedience and ethics intersect?

I concluded that blind obedience and ethics cannot coincide, but then I had more questions. Should strict obedience depend on the scenario: emergencies or non-emergencies? How can we protect whistleblowers? Is it more ethical to express my doubts publicly on paper than by talking to superiors or peers? Is it possible or feasible to have time for discussion when everyday practice makes almost no room for reflection?

I hope that exploring these dilemmas will encourage meaningful conversations. Perhaps my doubts could catalyze change towards a more open dialogue.

End notes

- José Emilio Pacheco, Obediencia Debida: Irás y no volverás, 2nd ed. (México: Joaquín Mortiz, 1975), 34.

- M. Berenbaum, “Adolf Eichmann,” Encyclopedia Britannica, August 17, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Adolf-Eichmann.

- “Episiotomy: What you can expect,” Mayo Clinic, last modified July 9, 2021, accessed March 14, 2023, https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/labor-and-delivery/in-depth/episiotomy/art-20047282.

- Bindu Varkey, “Principles of Clinical Ethics and Their Application to Practice,” Med Princ Pract 30, no. 1 (2021): 17-28, doi:10.1159/000509119.

- Eric Cassell, “Consent or Obedience? Power and Authority in Medicine,” New England Journal of Medicine 352, no. 4 (2005): 328-330, doi:10.1056/NEJMp048188.

- Andrew Brainard and Heather Brislen, “Viewpoint: Learning Professionalism: A View from the Trenches,” Academic Medicine 82, no. 11 (2007): 1010-4, doi:10.1097/01.ACM.0000285343.95826.94.

- Catherine Caldicott and Kirsten Faber-Langendoen, “Deception, Discrimination, and Fear of Reprisal: Lessons in Ethics from Third-Year Medical Students,” Academic Medicine 80, no. 9 (2005): 866-73, doi:10.1097/00001888-200509000-00018.

- Chris Feudtner, Dimitri Christakis, and Nicholas Christakis, “Do Clinical Clerks Suffer Ethical Erosion? Students’ Perceptions of Their Ethical Environment and Personal Development,” Academic Medicine 69, no. 8 (1994): 670-679. doi:10.1097/00001888-199408000-00017.

- “The Journal: Teaching Obedience,” FASPE (Fellowships at Auschwitz for the Study of Professional Ethics), accessed March 14, 2023, https://www.faspe-ethics.org/2019-journal-teaching-obedience/.

Bibliography

- Berenbaum, M. “Adolf Eichmann.” Encyclopedia Britannica, August 17, 2022. https://britannica.com/biography/Adolf-Eichmann.

- Brainard, Andrew, and Heather Brislen. “Viewpoint: Learning Professionalism: AView from the Trenches.” Academic Medicine 82, no. 11 (2007): 1010-4. doi:10.1097/01.ACM.0000285343.95826.94.

- Caldicott, Catherine, and Kirsten Faber-Langendoen. “Deception, Discrimination, and Fear of Reprisal: Lessons in Ethics from Third-Year Medical Students.” Academic Medicine 80, no. 9 (2005): 866-73. doi:10.1097/00001888-200509000-00018.

- Cassell, Eric. “Consent or Obedience? Power and Authority in Medicine.” New EnglandJournal of Medicine 352, no. 4 (2005): 328-330. doi:10.1056/NEJMp048188. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15673798/.

- “Episiotomy: What you can expect.” Mayo Clinic. Last modified July 9, 2021. Accessed March 14, 2023. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/labor-and-delivery/in-depth/episiotomy/art-20047282.

- Feudtner, Chris, Dimitri Christakis, and Nicholas Christakis. “Do Clinical ClerksSuffer Ethical Erosion? Students’ Perceptions of Their Ethical Environment and Personal Development.” Academic Medicine 69, no. 8 (1994): 670-679. doi:10.1097/00001888-199408000-00017.

- Pacheco, José Emilio. Obediencia Debida: Irás y no volverás, 2nd ed. (México: Joaquín Mortiz), 1975.

- “The Journal: Teaching Obedience.” FASPE (Fellowships at Auschwitz for the Study of Professional Ethics). Accessed March 14, 2023. https://www.faspe-ethics.org/2019-journal-teaching-obedience/.

- Varkey, Bindu. “Principles of Clinical Ethics and Their Application to Practice.” Med PrincPract 30, no. 1 (2021): 17-28. doi:10.1159/000509119.

LUISA ALANÍS SÁENZ, a medical student (’23) at the Instituto Tecnológico de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, is currently completing her Social Service year as a research assistant at the Rheumatology and Immunology Department of the Instituto de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán in Mexico City. She aspires to become a hematologist.

Submitted for the 2022–23 Medical Student Essay Contest

Leave a Reply