Melissa Yeo

Ontario, Canada

|

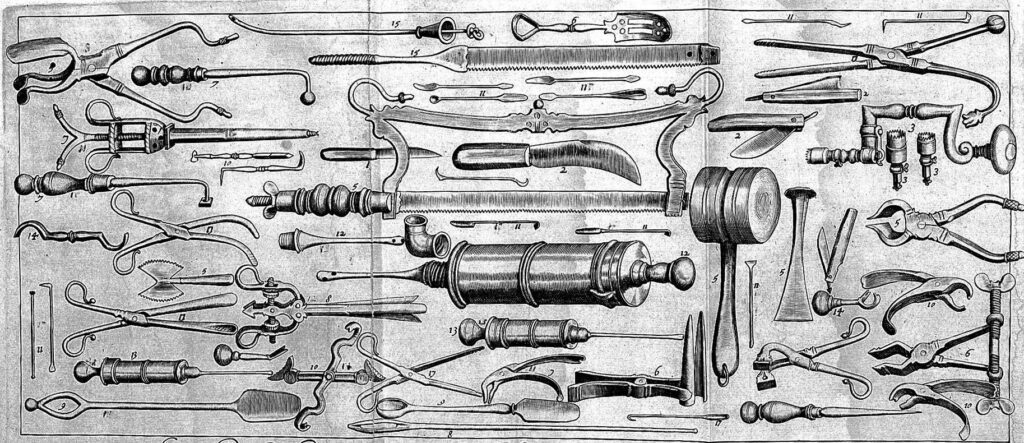

| Instruments in a Surgeon’s Chest (click to enlarge). From The surgeons mate or military and domestique surgery, John Woodall, 1639. Wellcome Collection. Public domain. |

Scurvy, yellow fever, and typhus were considered “the three Great Killers of seamen.”1 Hygiene and diet were very poor aboard eighteenth-century sailing vessels, as ships were often overstocked with men to account for ensuing losses while at sea.2 The sanitation on board these ships was considered as bad or worse than the slums of England and Paris. The lower decks of ships where the crew boarded smelled of sweat and rot, and men wore the same damp clothes for months at a time. Live animals often stayed on board to be used for slaughter, and food supplies were ravaged by mold or larvae. The only method of sanitation involved vinegar or fumigation; diseases quickly spread among the crew.3 The usual diet of a sailor was made up of biscuits, beer, a ration of salted beef or pork, cheese, butter, oatmeal, and dried beans.4

Medical treatment was dangerous and often extreme. In 1608, the Royal Navy began commissioning hospital ships to travel with their fleet for the sick and wounded.5 Aboard a vessel, a barber-surgeon was responsible for the care and treatment of the wounded and ill.2 Barber-surgeons let blood, lanced boils, pulled teeth, and “amputation was the most common operation, along with sewing up abdominal wounds.”2 Most surgeons began their careers on the sea to gain experience and credentials, and often had an apprentice to assist them. Their tools were wrapped in oiled rags to prevent rust and their supplies stored in a surgeon’s chest.2 At sea, surgeons were also permitted to prescribe medications.

John Woodall was considered the “father of sea surgery,” having an impressive career in naval medicine. He began apprenticing at the age of sixteen and eventually became the Surgeon General of the East India Company, in charge of appointing surgeons to vessels and keeping surgeons’ chests well stocked.2 Woodall published the first textbook in any language for surgeons at sea, The Surgeons Mate, in 1617. His book listed the instruments and medicines in the surgeon’s chest, described wounds, gave instructions for amputation, identified various medical ailments, and included “a lengthy discourse on scurvy, the first ever published in English.”2 Woodall’s text was revolutionary for the time, as it described treatment so compassionately and simply that the crew of a ship could follow along if a surgeon was not present.2

The Sick and Hurt Board was a division of the Royal Navy’s civil administration from the 1740s until 1806 and marked the beginning of a uniform health system in Britain. In the early days of the Board, it was only operational during wartime. But as seamen’s health became a greater financial concern for the Navy, a more permanent organization was established as “trained seamen, sick, or even worse dead, were literally a ‘dead loss’ to the service and very difficult to replace.”6 The Sick and Hurt Board commissioners were not medically qualified in the early years of the organization, so they partnered with the College of Physicians to discuss diseases among seamen. By 1796, however, most of the Sick and Hurt Board commissioners were doctors, with better testing and care options available to sailors.7

As new naval hospitals like Haslar and Stonehouse began to appear in Britain, more seamen were available on land for the Board to test medical treatments. New hygiene regulations were put in place to prevent sailors from deserting the hospitals. Hospitals were to be kept clean and not overcrowded. Each man was to be given his own bed, with clean linen changed every three weeks. Alcohol was not permitted, and the men were required to be separated by ailment. The Sick and Hurt Board also paired with the Victualling Board to arrange the transport of more vegetables on vessels to North America, to preserve the health of crewmen.7 Although fresh food did seem to decrease the number of scurvy cases, the Sick and Hurt Board also conducted trials to find more concrete cures.7

Abolished in 1806, the Sick and Hurt Board was one of the first public health organizations. Advancements in naval medicine during the eighteenth century are evident at sea and on land through the development of medical texts for barber-surgeons, improved sanitation practices in naval hospitals, trials of new remedies for disease, and the beginning of a uniform healthcare system in Britain.7

End notes

- James Lind, “Means of preventing sickness from being introduced into a Ship or Fleet,” in The Health of Seamen: Selections from the works of Dr. James Lind, Sir Gilbert Blaine and Dr. Thomas Trotter, ed. Christopher Lloyd (London: Navy Records Society, 1965), 28-32.

- Joan Druett, Rough Medicine: Surgeons at Sea in the Age of Sail (New York: Routledge, 2001), 50-65.

- Stephen Bown, Scurvy: How a surgeon, a mariner, and a gentleman solved the greatest medical mystery of the age of sail (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2003), 22-35.

- Kenneth Carpenter, The History of Scurvy and Vitamin C (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 10-27.

- Jessica Clark, “Risk and Reward on the Seas” (lecture, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON, February 1, 2017).

- Pat Crimmin, “The Sick and Hurt Board and the problem of scurvy,” Journal for Maritime Research, no. 1 (2013): 47-53.

- Pat Crimmin, “The Sick and Hurt Board and the health of seamen, C. 1700-1806,” Journal for Maritime Research, no. 1 (1999): 48-65.

Bibliography

- Baron, Jeremy. “Sailors’ scurvy before and after James Lind—A reassessment.” Nutritional Reviews 67, no. 6 (2009): 315-322.

- Bartholomew, Michael. “James Lind and scurvy: A revaluation.” Journal for Maritime Research 4, no. 1 (2002): 1-14.

- Bown, Stephen. Scurvy: How a surgeon, a mariner, and a gentleman solved the greatest medical mystery of the age of sail. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2003.

- Carpenter, Kenneth. The History of Scurvy and Vitamin C. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Clark, Jessica. “Risk and Reward on the Sea.” Lecture at Brock University, St. Catharines, ON, February 1st, 2017.

- Crimmin, Pat. “The Sick and Hurt Board and the health of seamen C. 1700–1806.” Journal for Maritime Research 1, no.1 (1999): 48-65.

- Crimmin, Pat. “The Sick and Hurt Board and the problem of scurvy.” Journal for Maritime Research 15, no. 1 (2013): 47-53.

- Druett, Joan. Rough Medicine: Surgeons at Sea in the Age of Sail. New York: Routledge, 2001.

- Lind, James. A treatise of the scurvy: In three parts. Containing an inquiry into the nature, causes, and cure, of that disease together with a critical and chronological view of what has been published on the subject By James Lind, M.D. Edinburgh: Printed by Sands, Murray, and Cochran for A. Kincaid & A. Donaldson, 1753.

- Lind, James. “Means of preventing sickness from being introduced into a Ship or Fleet.” In The Health of Seamen: selections from the works of Dr. James Lind, Sir Gilbert Blane and Dr. Thomas Trotter, edited byChristopher Lloyd, 28-32 London: Navy Records Society, 1965.

- Magiorkinis, Emmanuil, Apostolos Beloukas, and Aristidis Diamantis. “Scurvy: Past, Present, Future.” European Journal of Internal Medicine 22, no. 2 (2011): 147-152.

- Sutton, Graham. “Putrid gums and ‘Dead Men’s Cloaths’: James Lind aboard the Salisbury.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 96, no. 12 (2003): 605-608.

MELISSA YEO is a first-year medical student at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine in Sudbury, Ontario, Canada. She has a Master of Clinical Science in pathology from Western University and a Bachelor of Science from Brock University. Her career interests include pathology, surgery, and the history of medicine.

Submitted for the 2022–23 Medical Student Essay Contest

Winter 2023 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply