Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

|

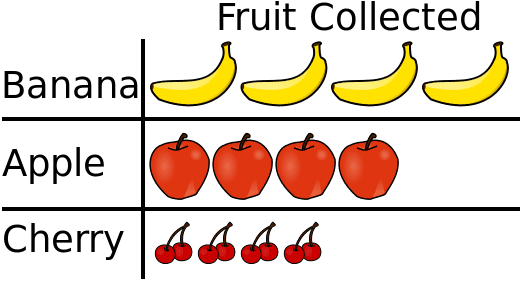

| A misleadingly scaled pictogram, in which there seem to be more bananas collected than the other fruits. “Pictograph not aligned and different size” by Smallman12q on Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 3.0. |

|

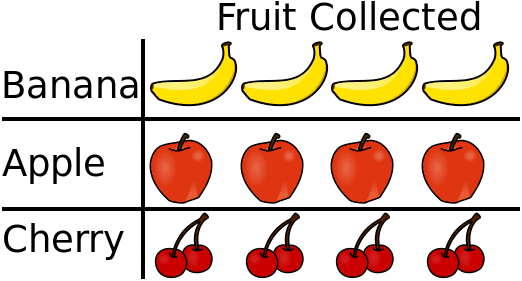

| A correctly scaled pictogram, in which the fruit icons are of nearly equal size. “Pictograph aligned and similar size” by Smallman12q on Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 3.0. Image descriptions adapted from Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 3.0. |

“Ninety percent of everything is crap.”– Sturgeon’s law1

“Garbage in, garbage out.” – Early computer-speak for “nonsense input produces nonsense output”

The publishing of studies in medical journals is based on trust. When journal editors receive a manuscript, they first look at the title to determine if the subject may be appropriate for their journal. They may quickly look at the study before sending it on to a “peer reviewer.” This reviewer, who is usually not paid for this task, is someone with expertise and experience in the subject treated in the manuscript. Neither the editor nor the reviewer in many cases stops to ask if the study has falsified data or was ever conducted at all.2 When a study is found to contain fabricated data, the journal that published it needs to print a “retraction notice,” telling its readers why the study is unreliable and was therefore retracted. Often these retraction notices are not seen or are ignored, and a retracted—and therefore invalid—study continues to be cited by other authors. These studies are “dead,” but are still cited as though they were “alive.” Thus, they are “zombie articles.”3 Some authors use this term too broadly, to describe any article that lacks credibility.4

Physicians in academic settings are judged and promoted, in part, by the number of articles they publish. They may then engage in research that they are not equipped to perform or may even produce fake articles.5 More publications lead to a better chance of promotion.6 Fraudulent research may also make recommendations for treatment dangerous. Physicians are taught to believe in “systematic reviews.” In these reviews, many articles on one aspect of treatment (or diagnosis) are analyzed in order to come to some conclusion. However, if “fatally flawed or untrustworthy” studies are included in systematic reviews, the reviews become worthless. “If trials are biased, systematic reviews based on them are biased…The literature is awash with low quality, [statistically] underpowered, single centre trials.”7

Some abuses are flagrant. Several came from an author who claimed to work at a research institution that did not exist.8 Some of his co-authors did not know they were listed as co-authors, and they did not contribute to the studies. These articles were published in prestigious (“high impact”) journals, but were all fabricated. Even after it became known that this was fraud, none of the articles were retracted. Only 4,844 biomedical studies were retracted between 2009–2020, and thirty countries accounted for about 95% of them.9 Among the leaders were China (33%), the US (19%), India (7%), and Italy and Japan (4% each). Among the reasons for retraction were mistakes and inconsistent data (32%), manipulated images (22%), plagiarism (14%), and 12% had “multiple” reasons. These articles had been cited over 140,000 times on Google Scholar (96,000 in Dimensions).

A detailed study reported in Smith10 looked at 153 trials submitted to Anaesthesia for which the study author was able to obtain individual patient data. He found a little under half of these trials, 44%, to contain “untrustworthy data.” Many of the manuscripts were submitted by authors from Egypt, Iran, India, China, Japan, Turkey, and South Korea. Further analysis by Joan Ioannidis of a year’s worth of submissions from these countries to Anaesthesia showed the proportion of suspect articles to range from 18% (Japan) to 100% (Egypt).11 These investigations clearly show a need to ask manuscript authors for individual patient data.12,13 The countries named above may account for more than 200,000 fraudulent clinical trials every year, while it is simultaneously possible that data fraudsters and manipulators in the US and Europe are more skilled at hiding fraud from reviewers than are authors from these countries.14

The “zombie” status of some retracted papers is evident.15 Twenty-seven articles from one author were retracted by the journal that published them. Later, these retracted articles were found to be cited in eighty-eight different articles. The authors and the editors of journals allowing the citation of retracted articles were, with some exceptions, uninterested in publishing the fact that retracted articles were cited. An investigation in 1998 (discussed in Brainard16) showed that 281 of 299 citations of retracted articles in the MEDLINE database did not note that the articles had been retracted.

The ambition for promotion and recognition, and the desire of pharmaceutical companies to profit from medications that produce positive results, distort and pollute the system of medical communication. In the 1980s, “research authorities insisted that fraud was rare.”17 Today, there are fears that 20% of published studies are dishonestly reported.18 Patients are the ultimate victims of this deceit.

References

- “Sturgeon’s law.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sturgeon%27s_law.

Theodore Sturgeon was an American science fiction author. Upon observing that 90% of science fiction was of low quality, he pronounced his law. - Richard Smith. “Time to assume that health research is fraudulent until proven otherwise?” BMJOpinion, July 5, 2021. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2021/07/05/time-to-assume-that-health-research-is-fraudulent-until-proved-otherwise/.

- May Berenbaum. “On zombies, struldbrugs, and other horrors of the scientific literature,” PNAS, 18(32), 2021.

- John Ioannidis. “Hundreds of thousands of zombie randomised trials circulate among us,” Anaesthesia, 76(4), 2021.

- David Altman. “The scandal of poor medical research,” BMJ, 308(6924), 1994.

- Smith, “Time to assume?”

- Ian Roberts et al. “The knowledge system underpinning healthcare is not fit for purpose and must change,” BMJ, 350. 2015.

- Smith, “Time to assume?”

- Catalin Toma and Liliana Pandureanu. “An exploratory analysis of 4844 withdrawn articles and their retraction rates.” bioRxiv, October 18, 2021. doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.30.462625.

- Smith, “Time to assume?”

- Ioannidis, “Hundreds.”

- Roberts et al, “Knowledge system.”

- Ioannidis, “Hundreds.”

- Ioannidis, “Hundreds.”

- Jeffrey Brainard. “‘Zombie papers’ just won’t die. Retracted papers by notorious fraudster still cited years later,” Science, June 27, 2022.

- Brainard, “Zombie papers.”

- Smith, “Time to assume?”

- Smith, “Time to assume?”

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Leave a Reply