Nicolas Roberto Robles

Badajoz, Spain

Je suis comme le roi d’un pays pluvieux,

Riche, mais impuissant, jeune et pourtant très-vieux,

Qui, de ses précepteurs méprisant les courbettes,

S’ennuie avec ses chiens comme avec d’autres bêtes.

Rien ne peut l’égayer, ni gibier, ni faucon,

Ni son peuple mourant en face du balcon.

I am like the king of a rainy country, rich

but helpless, still young but already decrepit,

scorning his fawning tutors, wasting his time

on dogs and other beasts and having no fun.

Nothing amuses him, neither hawk nor hound

nor subjects dying at the palace gate.

– From “Spleen” (III) by Baudelaire, Les Fleurs du Mal

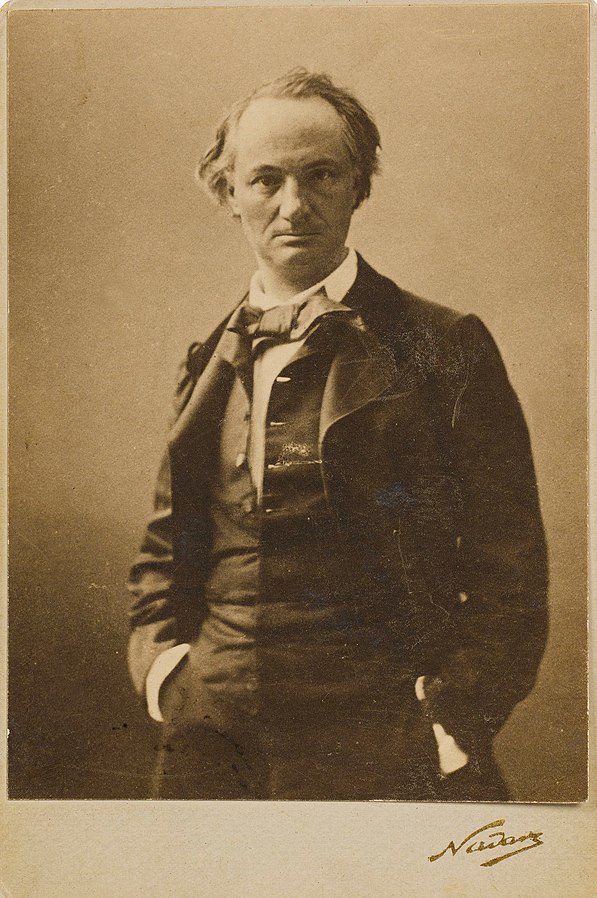

In colloquial speech, the word “spleen” can also refer to a state of mind. The definition was popularized by the French poet Charles-Pierre Baudelaire as meaning a state of melancholy, boredom, and dissatisfaction with life that lacks a definite cause. The connection between “spleen” and melancholy comes from Greek medicine and from the concept of humors, beginning with Hippocrates and later developed extensively by Galen. The humors included black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood. The Greeks thought that the spleen secreted black bile, which was associated with melancholy.1

Charles Baudelaire, son of a former priest, was born in Paris in 1821. After his father died in 1827, his mother married a military man. Baudelaire never accepted his stepfather, and family conflicts became constant. In 1839 Baudelaire was expelled from the lycée for lack of discipline. Later, he enrolled in the Faculty of Law at the University of Paris, and he began to lead a bohemian lifestyle. In that period, he knew Sarah (nicknamed “Louchette”), a prostitute who inspired some of his poems and also infected him with syphilis. To get him away from this life, his adoptive father sent him in 1841 to India, but after a stopover in Mauritius, Baudelaire returned to Paris and to his old disorderly ways. He continued to frequent literary and artistic circles and scandalized all of Paris with his relations with Jeanne Duval, a “mulatre,” who would inspire some of his most brilliant and controversial poetry.

As he was of age, he claimed his father’s inheritance, but his life as a dandy drove him to squander half of his inheritance. In response, his parents convened a family council and appointed a legal guardian to control his assets. In 1844, the family also appointed a notary to administer his estate and assigned him a small monthly income, a situation that deepened the familial strife.

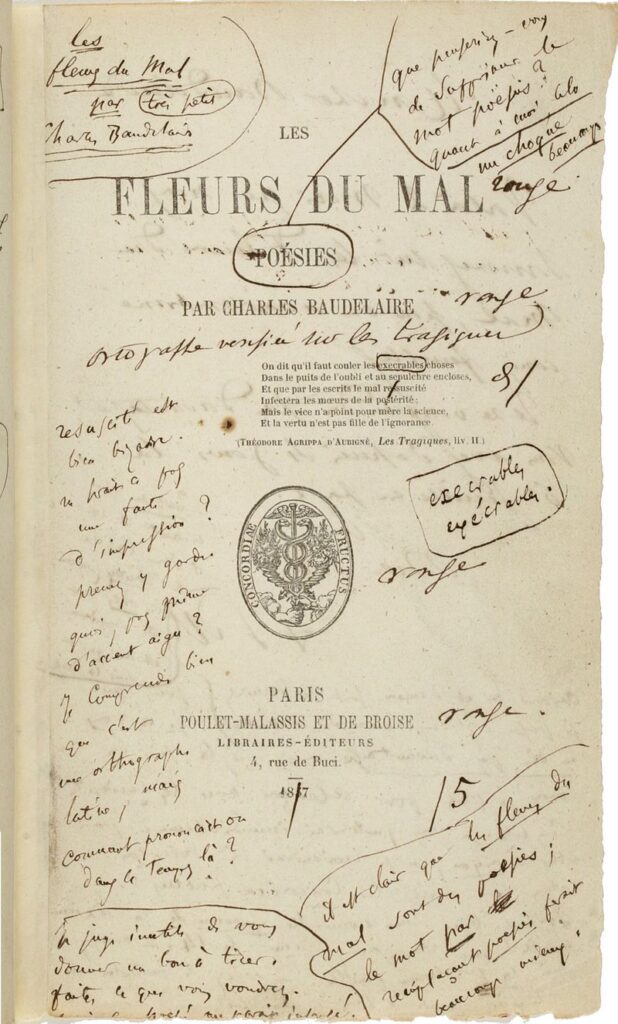

In early 1845, he began to consume hashish and devote himself to art criticism. Faced with the first symptoms of syphilis and amid a strong emotional crisis, he attempted suicide in June of that year. The publication of Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil) in 1857 by Poulet-Malassis caused the violent controversies around him to explode. This collection of poems, meticulously worked on for eight years, constituted his main work and marked a milestone in French poetry. Gustave Bourdin, in the July 5 edition of Le Figaro, considered his work “full of monstrosities,” and eleven days later, the court ordered a seizure of the collection and a trial of both the author and publisher. The resulting sentence was the removal of six poems from the volume and a fine to Baudelaire of three hundred francs.2

In January 1860, Baudelaire experienced an attack of dizziness, intense nausea, and difficulty walking upright. He recovered, but similar attacks would follow, and furthermore, there were periods of headaches. The syphilis had reached its tertiary stage. He became depressed, and the first episode of paralysis occurred in 1865, with aphasia and hemiplegia persisting until his death. In March 1866, an attack in a church in Namur, Belgium caused his mother to urgently transfer him to a clinic near the Arc de Triomphe, Dr. Emile Duval’s the “Établissement hydrothérapique de Chaillot.” Baudelaire remained speechless but lucid until his death in August of the following year. One of the characteristics of Baudelaire’s aphasia was that when asked about different things, he would always reply with a repetitious, blasphemous expression.2

Melancholy is a frequent topic in Baudelaire’s poetry. There are four poems about “spleen” in Les Fleurs du Mal; moreover, he published a collection of short prose poems entitled Spleen de Paris. The spleen thus became the fundamental category of his aesthetics and view of the world. He sees melancholy as deriving from the irremediable “tragedy” of human desire.3 For the poet, “spleen” is a pain of the soul, an existential concern, and an inexplicable anguish. It is not only about an exasperated form of the evil of the century of its romantic precursors, but a pathological state sometimes so absolute that it even takes on “the proportions of immortality.”4

Et de longs corbillards, sans tambours ni musique,

Défilent lentement dans mon âme ; l’Espoir,

Vaincu, pleure, et l’Angoisse atroce, despotique,

Sur mon crâne incliné plante son drapeau noir.

And giant hearses, without dirge or drums,

parade at half-step in my soul, where Hope

defeated weeps, and the oppressor Dread

plants his black flag on my assenting skull.

– From “Spleen” (IV), Les Fleurs du Mal

References

- Laín Entralgo, Pedro. Historia de la Medicina. Barcelona: Salvat, 1978.

- Dieguez, Sebastian, and Julien Bogousslavsky. Baudelaire’s aphasia: from poetry to cursing. Front Neurol Neurosci 2007;22:121-149.

- Pearson, Roger. “Melancholy and Satan.” In The Beauty of Baudelaire: The Poet as Alternative Lawgiver, Oxford Academic, September 2021, 108-126. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192843319.003.0006.

- Vendula Sochorcová. “L’ennemi de Baudelaire – Le Temps Comme une des Composantes du Spleen Baudelairien.” Études Romanes De Brno 2011;32(1).

NICOLAS ROBERTO ROBLES is professor of Nephrology at the University of Extremadura (Badajoz) and member of the Academy of Medicine of Extremadura.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 15, Issue 2 – Spring 2023

Leave a Reply