Matthew Turner

McChord, Washington, United States

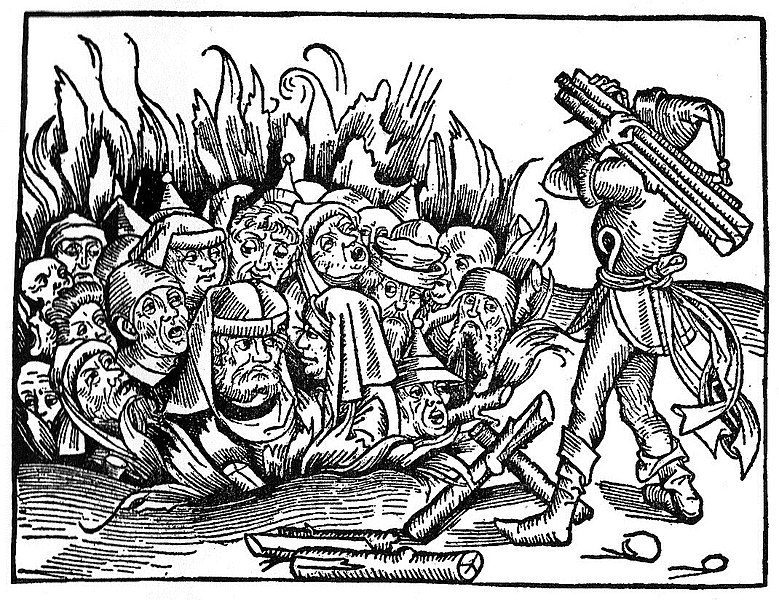

Massacre of Jews woodcut. 1493. From L. Golding, The Jewish Problem, Penguin, 1938. Via Wikimedia. Public domain.

Introduction

It is a story often repeated in medical textbooks: in 1492, Innocent VIII lay dying. His physician attempted the first recorded blood transfusion, transfusing the blood of three children into the deteriorating Pope. The treatment failed, and Innocent’s uneasy reign over Rome ended shortly afterwards. The story, set nearly 150 years before William Harvey published his theories on blood circulation,1 is probably apocryphal, and likely was intended to spread the anti-Semitic conspiracy theory of blood libel.

The origins of the story

Lindeboom traces the modern origins of the story to Pasquale Villari, an Italian author in the mid-nineteenth century. Villari writes of Innocent VIII’s decaying state, reduced to a “sort of stupor for some time… In vain [the court] had tried to revive [the Pope’s] exhausted energies. Then a Jewish physician proposed to try a blood transfusion by means of a new instrument… The difficult experiment was repeated three times, the result being that three boys lost their lives, without the Pope receiving any benefit for it.”2 Villari’s sources referred to the writings of Sismondi de Sismondi, a historian specializing in medieval Italian history. Writing a half-century earlier, Sismondi also spoke of a Jewish physician, the use of children’s blood, and the subsequent death of all the participants.2

It is from these nineteenth-century sources that modern iterations of the story originate. Although the details vary—some argue that the transfusion was in the form of a drink rather than a modern-style transfusion,1,3 with Maluf going so far as to describe the Pope’s treatment as “the sucking of blood from the arm veins of youths”4—a common theme is the clergyman’s Jewish physician. Duffin names him as Giacomo di San Genesia,5 while other sources name him as Abraham Meyre.3

Where do these stories originate? Brown traced the origins of the tale to Steven Infessura, a contemporary chronicler who wrote: “… three boys of ten years of age died because blood had been taken from their veins by a Jewish physician in an attempt to cure the Pope.”3

Lindeboom identifies a second primary source: Odorico Raynaldus, writing in the sixteenth century. Raynaldus describes: “… a Jew, a deceiver who promised cure, tapped blood from three ten-year-old boys, who died soon after it, to compound a potion for the Pope by a chemical process. When Innocent heard of it he cursed this atrocity, and ordered the Jew to be punished, but the latter soon escaped the torture by flight.”2

The scant evidence provided by Infessura and Raynaldus makes it doubtful that the episode took place. None of the other chroniclers of the period recorded this incident. Treatments involving blood existed solely in the domain of the barber-surgeon guilds of the day, not physicians, and Jewish doctors had been forbidden from treating Christians in a ruling renewed by the 1267 Vienna Synod.6

The propaganda piece

This story was likely meant to redirect focus from Innocent’s ineffective rule—a period marked by unrest—to a Jewish scapegoat.6 Innocent had shown some relative favor to Jewish physicians, allowing a man named Abram di Mayr de Balmes of Lecce to practice medicine without regard to person,7 thus contradicting the 1267 Council of Venice ruling. This individual may have been the inspiration for the mysterious Abraham Meyre3 mentioned in later stories. It may be that Raynaldus’s portrayal of the story—where Innocent rejects the physician’s treatment and attempts to punish him2—was an attempt by the chronicler to downplay the Pope’s sympathetic treatment of Jewish physicians.

Jews had long been a persecuted minority by medieval Europe and a scapegoat for horrors such as the Black Death,2 but Infessura’s and Raynaldus’s accounts touched upon an anti-Semitic conspiracy theory that had evolved over the prior centuries: blood libel.

This accusation, that Jews murdered Christians in order to obtain their blood for profane rituals, has a long history. An early case included the death of William of Norwich in 1144, when members of the local Jewish community were accused of ritually crucifying the child.8 The rumors of such rituals quickly spread across the continent; in 1171, thirty-two Jews were burned alive for the charge of ritual murder.8

Blood libel soon became an official policy of medieval institutions. Cardinal Odo, the Chancellor of the University of Paris, accused a rabbi that “you [Jews] eat the blood of the uncircumcised.”8 Further accusations quickly followed. One of the most infamous cases—the 1475 death of two-year-old Simon of Trent in Italy, for which fifteen Jews were convicted and at least the majority burned alive8-10—would have still been fresh in the public’s consciousness during Innocent VIII’s reign.

The tie between blood libel and medicine was established by Thomas of Cantimpre in 1258. He wrote of a mysterious illness suffered by Jewish men, curable only by Christian blood. Thomas believed that this ailment involved hemorrhages, itself a reference to Matthew 27:25, where the Jews tell Pontius Pilate, “His blood be on us and on our children.”8 The idea spread, and in the eyes of Christians, blood libel took on both a religious and a medicinal meaning.

Conclusion

With this undercurrent of blood libel in mind, when we re-examine the story of Innocent VIII’s purported transfusion, it becomes clear that the tale was just one in a long series of anti-Semitic stories that circulated through the medieval European consciousness.8 The original story may have been of some use to Innocent’s public image, portraying him as a victim of a profane experiment while distracting from his failures as a leader, but over the centuries the story evolved into a curious anecdote of medical history. It is important that we regard the original sources of the story and the atmosphere in which they circulated.

References

- Learoyd P. The history of blood transfusion prior to the 20th century – Part 1. Transfusion Medicine. 2012;22(5):308-314. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3148.2012.01180.x.

- Lindeboom GA. The Story of a Blood Transfusion to a Pope. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 1954;9(4):455-459. doi:10.2307/24619486.

- Brown HM. The Beginnings of Intravenous Medication. Annals of Medical History. 1917;1(2):177-197.

- Maluf NSR. History of Blood Transfusion. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 1954;9(1):59-107. doi:10.2307/24619834.

- Duffin J. History of Medicine: A Scandalously Short Introduction. University of Toronto Press; 2021.

- Gottlieb AM. History of the First Blood Transfusion but a Fable Agreed Upon: The Transfusion of Blood to a Pope. Transfusion Medicine Reviews. 1991;5(3):228-235.

- Friedenwald H. Jewish Physicians in Italy: Their Relation to the Papal and Italian States. vol 28. Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society; 1922.

- Ehrman A. The Origins of the Ritual Murder Accusation and Blood Libel. Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought. 1976;15(4):83-90. doi:10.2307/23258406.

- Dundes A. The Blood Libel Legend: A Casebook in Anti-Semitic Folklore. University of Wisconsin Press; 1991.

- Hsia RPC. (1992). Trent 1475: Stories of a Ritual Murder Trial. Yale University Press.

MATTHEW TURNER is a current transitional year intern at Madigan Army Medical Center. He is interested in the intersection of medicine and history.

Submitted for the 2022–23 Medical Student Essay Contest

Leave a Reply