Sally Metzler

Chicago, Illinois, United States

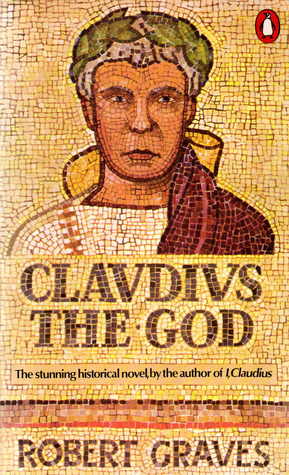

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Drusus Nero Germanicus, Emperor of Rome from 41 to 54 CE, though known to historians, became a household name in 1970 with the advent of the popular television series I, Claudius. But he had already gained attention several decades earlier, engendered by British author Robert Graves, who immortalized him in his books I, Claudius and the sequel, Claudius the God, published in 1934 and 1953 respectively. Tales of palace intrigue, war, tyranny, jealousy, and moral depravation fill the pages, making for fascinating reading. Graves fashioned his two volumes as “autobiographies” penned by Claudius and furnishes the reader with an “eyewitness” account of the vicissitudes of Claudius’ ancestors and kinsmen. Of curiosity and horror is the rule of the infamous Caligula, the nephew of Claudius and whom he succeeds as emperor. Claudius spares no details of Caligula’s cruelty. The countless incidents of murder and torture deliver chilling impressions.

Nestled among the pages describing the various adventures and conspiracies are sound bites that under current nomenclature would be considered health and wellness tips. For example, the flowering plant hellebore from the town of Anticyra in Thessaly alleviated mental weakness.1 Prayer, common sense, and cabbage leaves alleviated most common ailments.2 And if suffering from a cold, blowing one’s nose was to be avoided at all costs, as it exacerbated the symptoms by increasing the discharge and inflaming the membranes: “Better to let it run. Wipe, don’t blow.”3

Claudius expatiates on the sage advice of his physician Gaius Stertinius Xenophon, who cared for him across the decades. Born c. 10 BCE on the Greek Island of Kos, Xenophon was in good company. Hippocrates also hailed from Kos, and Tacitus recounted that Claudius averred Xenophon himself descended from Asclepius.4 Xenophon the physician is not to be confused with his much more famous namesake, Xenophon of Athens, the great military leader, philosopher, and historian, who lived centuries earlier (430 – ca. 355 BCE).

Xenophon appears to have come to the attention of Claudius through Herod II (also known as Herod Agrippa, 11 BCE – 44 CE), a confidant and dear friend of Claudius for many years. While visiting Rome, Herod advised Claudius that he should take better care of himself, his health was at risk, and he should acquire sound medical care. Discussing the virtues and vices of various physicians, Herod II recommended Xenophon, especially for his reasonable approach and adherence to the motto of Asclepius: Cure quickly, safely, pleasantly.5 Xenophon shunned violent purges and emetics in favor of diet, exercise, massage, and botanical remedies. He cured Herod II once of a violent fever, prescribing an elixir of the distilled leaves of a yellow flower called aconite. He had also advised Herod to be abstemious with drink and cautious with spices. Further, Herod had lavished praise on Xenophon for his surgical skills, noting he knew every bone and muscle in the body, thanks to his experience on the battlefield.6 He had accompanied Germanicus, the brother of Claudius, on his final campaign.7

Hereby convinced of Xenophon’s merits, Claudius sent for him. Describing their first encounter, he remarks that Xenophon appeared to be around fifty. Wasting little time with pleasantries, he begins the examination: “Your pulse. Thanks. Your tongue. Thanks… Eyes somewhat inflamed. Can cure that. I’ll give you a lotion to bathe them with. Stand up, please. Yes, infantile paralysis. Can’t cure that, naturally. Too late. Could have done so before you stopped growing.”8 Claudius walked with a limp and suffered from a formidable stammer, making him the subject of ridicule throughout his life. He enumerates for Xenophon other afflictions since birth: “Malaria, measle, colitis, scrofula, erysipelas…the whole battalion,” except “epilepsy, venereal disease and megalomania”!9

Xenophon displays complete confidence in his knowledge and abilities; he goes so far as to inform Claudius that he knows his dreams, and would have no hesitancy interpreting them, but the law forbids this. After he thoroughly examines Claudius, he assures him that he has many more years of life if he adheres to his advice: avoid reading too much so as to prevent fatigue; abstain from eating too much nor too fast so as to prevent stomach cramp and ensuing “cardiac passion”; and admit to twice-daily massages of twenty-minute duration.

This first meeting was most auspicious for both doctor and patient. Aside from the general lifestyle advice proffered Xenophon proffered, he nearly cured Claudius of his stammer and frequent tremors by prescribing bryony. After ingesting the concoction of bryony, a herbaceous vine related to the gourd family, Claudius remarked “For the first time in my life I knew what it was to be perfectly well. I followed Xenophon’s advice to the letter and have hardly had a day’s illness since.”10 This is high praise for any physician, let alone from a Roman emperor.

Not surprisingly, a fruitful life-long doctor-patient relationship ensued. Xenophon had many palliatives to recommend. Vermouth was a fine sedative, as well as being enjoyable with a fine meal.11 He also found time to engage in research and was said to have written a treatise on the muscles of the heart. Until the end of the emperor’s life, Xenophon appeared to do more good than harm despite the primitive medical knowledge of the era. Unfortunately, though he served Claudius honorably and loyally, he came under suspicion of poisoning him, and much conjecture suggests he was responsible for his death. According to Tacitus, Xenophon gave advice to Agrippina, the second wife of Claudius, on how to poison him.12 But the true cause of death remains cryptic, and thus the reputation of Xenophon will remain forever shrouded in rumor.

End notes

- See p. 50, Robert Graves, I, Claudius, New York: Vintage International, 1989.

- See p. 200, Robert Graves, Claudius the God, New York: Vintage Books, 1962.

- Graves, Claudius the God, p. 206.

- See Annals XII.61, Complete Works of Tacitus. Tacitus. Alfred John Church. William Jackson Brodribb. Sara Bryant. Edited for Perseus. New York: Random House, Inc., reprinted 1942.

- Graves, Claudius the God, p. 201.

- Ibid, p. 201.

- Xenophon’s father was also named Xenophon, and he is said to have served Drusus, the father of Claudius. See Graves, Claudius the God, p. 201.

- Graves, Claudius the God, p. 202.

- Ibid, p. 202.

- Ibid, p. 204.

- Ibid, p. 514.

- Aitor Blanco Pérez, “The doctor of Claudius honoured at Kos,” Judaism and Rome, 2018. https://judaism-and-rome.org/doctor-claudius-honoured-kos.

SALLY METZLER, PhD, is the director of the art collection at the Union League Club in Chicago.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 15, Issue 1 – Winter 2023

Leave a Reply