Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

|

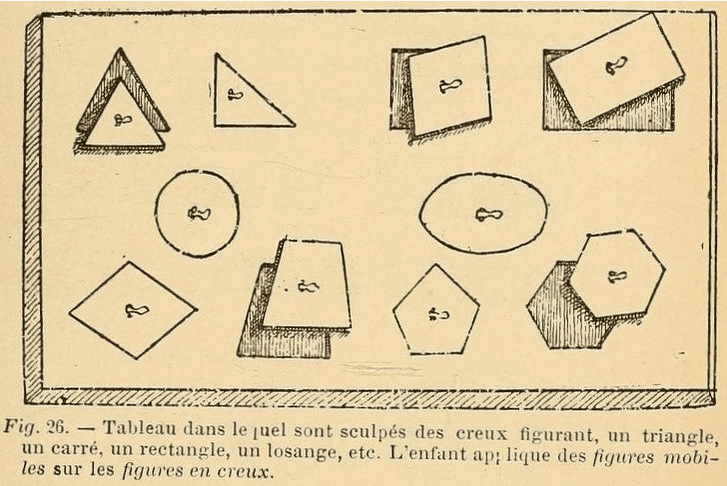

| Drawing of a children’s puzzle with different shaped pieces and holes. From Assistance, traitement et éducation des enfants idiots et dégénérés: rapport fait au Congrès National d’assistance publique (session de Lyon, juin 1894) by Bourneville (Paris: Aux bureaux du Progrès médical [etc.], 1895), p. 233. Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine via Internet Archive. |

“Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale.”

– Rudolf Virchow, M.D.

Désiré-Magloire Bourneville, M.D. (1840–1909), was born into a family of modest means. He earned his medical degree in 1865 in Paris. He is known today, if he is remembered at all, as the physician who first described tuberous sclerosis, originally called Bourneville’s disease. In an 1880 paper, he described a fifteen-year-old girl with seizures, developmental delay, and a persistent papular eruption on her nose, cheeks, and forehead. Autopsy revealed hard masses (“tubers”) in the cerebral cortex. We know today that this is an autosomal dominant condition with mutations of chromosomes nine and sixteen. In addition to central nervous system and skin lesions, tubers are also present in the heart and kidneys. The prevalence is 1/5,000–1/10,000 live births.1

Bourneville’s other achievements dwarf his discovery of tuberous sclerosis. He was considered the “leading continental authority on all that concerned mentally abnormal children.”2 It has been said that he “ought to be thought of as the father of pediatric neurology because of his significant contributions to the field.”3 Lagerkvist writes that Bourneville was a pediatric neurologist and physical medicine specialist before these terms existed.4

He was also a writer, journal editor, and politician, having served in Parliament as a representative of the extreme left from 1883–1889, where he strongly advocated for reform of the French health system.5,6 Most of his medical career was spent at the Bicêtre Hospital in Paris (1879–1905). The Bicêtre had opened in 1642 as an orphanage. Later it became, in succession, a prison, an asylum, and finally, a hospital.7 The “appalling children’s ward”8 at Bicêtre was described by a journalist in 1882 as lacking air, light, linens, and cleanliness.9 Bourneville had a heterogenous group of patients under his care. It included children with developmental disabilities (“idiots”), epilepsy, cerebral palsy, hydrocephalus, congenital and acquired neurologic disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (retrospectively10), and tuberous sclerosis.

Bourneville pushed for reforms in the country’s medical system as well as for the Bicêtre. He was a Mason and intolerant of religion when it delayed progress in health care. Nursing was done (much to his dismay) by untrained nuns and friars. He said they engaged in “archaic practices” and were more interested in having patients enter the Church than in giving care.11 He started the first French secular nursing school and wrote a textbook for nurses. He also helped “his” nurses obtain better living quarters and salaries.12

Obstetric care was haphazard in Bourneville’s day. He convinced the authorities to approve the concept of “childbirth centers,” which were to be staffed by physicians who had successfully completed a course in obstetrics. Midwives were required to be certified via a licensing examination.13

He transformed his unit in the Bicêtre into a “department governed by a unique and groundbreaking model.”14 His guiding principles were, firstly, to fight incessantly for the dignity of these children,15 and secondly, that all children with any type of disability should receive an education.16 To put these ideas into effect was to swim alone against the current. The problem was the incompatibility of ideas of incurability versus educability. The majority thinking was that these children needed to be kept away from society (the “arrièré de l’asile – the retarded person who should be in an asylum”). They were considered impulsive, instinctive, and ready to “perform reprehensible acts.” If they were not already criminals, they were ready to “join the army of crime,” defective children who were delinquent to some degree.17 Against this rigid approach, Bourneville proposed the idea of the educability of many of his patients (the “arrièré de l’école – the retarded individual who will benefit from school”). Forging an unheard-of cooperation between physicians, nurses, educators, and paramedical personnel,18 a “medico-pedagogical” approach was used, based on adapting an educational plan to each child’s needs. These revolutionary innovations produced “violent attacks”19 from Bourneville’s contemporaries.

The children—the unit had both boys and girls together, up to age ten years—were taught, as needed, self-feeding, sphincter control, speech, balance, and walking. They practiced buttoning buttons and closing a hook-and-eye. They used parallel bars, stepstools, blocks, and puzzles for hand-eye coordination.20 The children had playtimes, walks, excursions, and visits from family.

Many of Bourneville’s reforms have been “inexplicably and unfairly forgotten.” After his death, France reverted to a system of institutionalizing (not educating) these “defective” children. The Children’s Department at Bicêtre was closed in 1929, a decade after Bourneville’s death.21 “It [then] took about fifty years for pediatricians and orthopedists in several countries to start getting interested in handicapped people.”22

For now, “silence envelopes the name of Bourneville.”23

References

- Mariana Gómez-López and Leonardo Palacios-Sánchez. “Désiré-Magloire Bourneville and his contributions to pediatric neurology,” Arquivosde Neuro-psiquiatria, 77(4), 2019.

- NA. “Obituary. D.M. Bourneville, M.D.,” BMJ, 1909.

- Gómez-López, “Contributions.”

- Bengt Lagerkvist. “Tillförde medicinsk kunskap om intellektuell nedsättning,” Läkartidningen, 119, 2022.

- Désiré-Magloire Bourneville. Wikipedia.

- Juan Zarranz. “Bourneville: a neurologist in action,” Neurosciences and History, 3(3), 2015.

- Bicêtre Hospital. Wikipedia.

- Zarranz, “Neurologist.”

- Yves Jeanne. “Désiré Magloire Bourneville, rendre leur humanité aux enfants “idiots,” Reliance 7(24), 2007.

- Michel Bader and Philippe Mazet. “Le concept de TDA et la France de 1890-1980: l’instabilité ou le village gaulois d’Asterix,” La Psychiatrie de l’Enfant, 58(2), 2015.

- Jacqueline Gateaux-Mennencier. “L’oeuvre médico-sociale de Bourneville,” Histoire des Sciences Médicales, 37(1), 2003.

- Jacqueline Gateaux-Mennencier. “Réprésentation psychologique et regulation sociale au XIXe siècle. L’ “arrieration” de l’ asile à l’institution scolaire/Ninteenth century notions of psychology and social order: ‘backwardness,’ from asylum to educational institution,” Sociétés Contemporaines, 13, 1993.

- Zarranz, “Neurologist.”

- Ibid.

- Jeanne, “Humanité.”

- Gómez-López, “Contributions.”

- Ibid.

- Lagerkvist, “Funktionsnedsaättning.”

- Jeanne, “Humanité.”

- [Désiré-Magloire] Bourneville. “Assistance, traitment et éducation des enfants idiots et dégénérés,” In Traitment Médico-pedagogique, Paris: Progrès Médical, 1895.

- Zarranz, “Neurologist.”

- Lagerkvist, “Funktionsnedsättning.”

- Gateaux-Mercier, “Répresentation.”

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Leave a Reply