JMS Pearce

Hull, England, United Kingdom

|

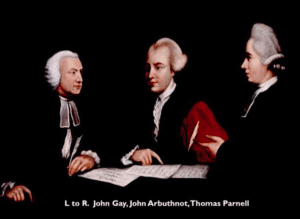

| Fig 1. John Gay, John Arbuthnot, and Thomas Parnell. |

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when transport was by horse and carriage, the opportunities for scholars and inventors to exchange ideas was limited. Consequently, there arose a number of small private gentlemen’s clubs, where members gathered for congenial or intellectual intercourse. Most were based in London. They were often viewed as icons of the power of old money and privileged connections. Starting in seventeenth-century coffeehouses, clubs developed devoted to business, the military, publishing, politics, and the professions, each with its own distinctive ethos1 but almost all wholly male-dominated.2

Many thrived on an exclusive class distinction, channels for self-promotion, and social prestige. Members could enjoy good dining, a haven of rest from domestic chores, luxurious premises, billiards, and libraries. Subscriptions were expensive and there were strict selection procedures. Amongst the most exclusive clubs were White’s (the oldest), Brooks’s, the Athenaeum, and Boodle’s.* Some became defunct. Perhaps the Athenaeum is the archetype, declaring that its members were elected for their achievements rather than their class, background, or political affiliation. It was a meeting place for artists, writers, and scientists, along with cabinet ministers, bishops, and judges.

However, within this veil of exclusivity was often concealed a group of brilliant men, anxious by sharpening their wits against each other to foster arts and science in an unstable but burgeoning industrialized England. Clubs could be valuable sources of exchange of ideas, knowledge, and socially beneficial forces. One such eccentric group was the Scriblerus Club.3

|

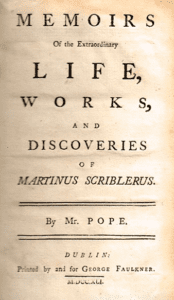

| Fig 2. Memoirs Of the Extraordinary Life, Works, and Discoveries of Martinus Scriblerus by Alexander Pope. |

Scriblerus Club

In 1714, a literary gentleman’s club was formed which included some of the most extraordinary and vivid satirists to have written in the English language. Under the name Scriblerus, they wrote varied and often humorous articles and essays, individually or in collaboration. They satirically reviled and poked fun at pompous people and their pompous utterings for excessively literal approaches to academic subjects, ranging from medicine to philosophy. They satirized the portentous abuses of learning wherever they occurred in an attempt to show a world they considered to be in terrible decline. In that vein, Alexander Pope described his melancholic view of an immoral, uncreative world of chaos in The Triumph of Dullness, closing lines of The Dunciad:

Religion, blushing, veils her sacred fires,

And unawares Morality expires.

Nor public flame, nor private, dares to shine;

Nor human spark is left, nor glimpse divine!

Lo! thy dread empire, Chaos! is restored;

Light dies before thy uncreating word:

Thy hand, great Anarch! lets the curtain fall;

And universal darkness buries all.

The Scriblerus wrote mocking caricatures with risible giants and midgets, diving competitions into the open sewer of Fleet-ditch, and Olympic-style pissing competitions: “Who best can send on high the salient spout, far-streaming to the sky; His be yon Juno of majestic size, With cow-like udders … (Pope’s Goddess in “Dunciad”).

Doctors too don’t escape their mockery. Swift in “A Consultation of Four Physicians upon a Lord that was dying” uses worthless jargon dressed as fake Latin:

First Doctor. Is his Honor sic? Præ lætus felis Puls. It do es beat veris loto de. Second Doctor. No notis as qui cassi e ver fel tu metri it. Inde edit is as fastas an alarum, ora fire bellat nite.Third Doctor. It is veri hei. (First line translates as: “Is his Honour sick? Pray let us feel his pulse. It does beat very slow today…”)

Its illustrious members (Fig 2) were:

Alexander Pope (1688–1744) was most influential in shaping the club’s image. He was the most epigrammatic of all English satirical authors, a brilliant wit, best known for An Essay on Criticism (1711), The Rape of the Lock (1712–14), and An Essay on Man (1733–34). In The Dunciad (1728) Pope pilloried a host of “hacks, scribblers and dunces” that provoked huge hostility and acrimonious abuse.

Jonathan Swift (1667–1745), Irish author, was another foremost satirist.4 He was Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, hence his sobriquet, “Dean Swift.” Besides the celebrated Gulliver’s Travels (1726), he wrote works such as Journal to Stella, and A Tale of a Tub. (1704). Swift and Arbuthnot were the principal productive contributors to the Scriblerus publications.

John Gay (1685–1732), a kindly poet and dramatist5 and master of satirical farce, is chiefly remembered as the author of The Beggar’s Opera, a work distinguished by good-humored satire.

Thomas Parnell (1679–1718) was a respected Irish poet and essayist whose scholarship Pope sought in his acclaimed (and lucrative) translation of Homer’s Iliad.

John Arbuthnot (1667–1735) (Fig 1), a man of brilliance and wit, was physician to Queen Anne and a mathematician. He created John Bull, the lasting symbol of Englishness, in his Law is a Bottom-less Pit; or, The History of John Bull,6 and was a principal active contributor in the club.

The prominent Tories Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford, and Henry St. John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke, were occasional members.

They fabricated a literary hack, Martinus Scriblerus. The name Martin was taken from John Dryden’s comic character Sir Martin Mar-all, (taken from L’Étourdi by Molière) a name that implied absurd errors. Scriblerus referred to scribbler or scrivener, then fashionable terms of disdain for a writer whose work was regarded as worthless or poorly composed. A scribbler was described in Samuel Johnson’s dictionary as a petty author; a writer without worth.

The collaboration of the five writers began in the Spring of 1714 when it provided the perfect satirical character for the informal group to parody current trends in hifalutin scholarship and learning. They had frequent, lively, witty meetings, usually at Arbuthnot’s house. Not surprisingly, this collection of mercurial talents led to disputes that sounded the death knell for the club.

However, the memoirs of Martinus Scriblerus were published in 1741 (Fig 2) by Alexander Pope, though much had been written by Arbuthnot. Pope and Jonathan Swift were the only surviving members.

The Scriblerians clearly stimulated each other to good effect. Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera arose from a suggestion of Jonathan Swift; their discussions are thought to have played important parts in Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. Pope’s The Dunciad contained work attributed to Martinus Scriblerus. Henry Fielding’s The Welsh Opera was a tribute to the Scriblerians and he chose his pen name, “Scriblerus Secundus.”

The Scriblerus came to an end in 1745. It is currently commemorated in The Scriblerian and the Kit-Cats, a biannual journal reviewing scholarly English literature and authors from the Restoration through to the late eighteenth century.

The Scriblerus Club, by skillfully insinuating political subversiveness and pessimism about human nature as subsequently identified by Goldsmith and Johnson, has often been invoked as the pinnacle of eighteenth-century satire.7

Other clubs

Several reputable clubs were devoted to the arts or theater: The Garrick, Savage, The Arts, Savile, Chelsea Arts, and the London Sketch Clubs. Fifty years after the start of the Scriblerus Club, the artist Joshua Reynolds and lexicographer and essayist Samuel Johnson, with Edmund Burke, the Anglo-Irish philosopher and politician, founded The Club or Literary Club in 1764. Dr. Johnson wanted a group “composed of the heads of every liberal and literary profession” to “have somebody to refer to in our doubts and discussions, by whose Science we might be enlightened.” Driven mainly by Edmund Burke, it evolved as a political organ. It still meets at the exclusive Brooks’s in St James Street.

The Kit-cat Club met in Christopher Cat’s tavern near Temple Bar and took its name from his mutton pies known as “Kit-cats.” It was a distinguished, influential club composed of republican Whig politicians.

The Other Club was another British political dining society founded in 1911 by Winston Churchill and the eminent barrister F. E. Smith; the Literary Club had rejected them both, because they were considered too controversial. Members met fortnightly at the Savoy Hotel until it ceased in the 1970s.

The Lunar Society8 and the X Club were immensely productive and influential scientifically orientated groups. They were gradually subsumed but not replaced by the Royal Society, Society of Antiquaries, Geological Society, and Linnaean Society. Their exclusivity was disdained and elitism has become an inverted snobbish and pejorative term that conceals its principal purpose, the quest for high standards of invention and discovery.

By the end of the nineteenth century, as the population grew, universities took a major role in widening education and research. University staff and student numbers dramatically increased. This often dictated more structured and formalized learning. Conferences and symposia expanded hugely in frequency and size. Inevitably, universities forfeited the personal intimacy, ingenuity, academic liberalism, and unrestricted candor of the smaller, more exclusive gatherings and societies of times past.

End note

*Scores of similar private clubs were established in European cities. There are also many in the US, including the Knickerbocker Club, New York; Union Club, New York; Algonquin Club, Boston; University Club of Washington, D.C.; and The Cliff Dwellers Club, Chicago.

References

- Black BA. Room of His Own: A Literary-Cultural Study of Victorian Clubland. Athens: Ohio University Press. 2012.

- Milne-Smith A. London Clubland: A Cultural History of Gender and Class in late-Victorian Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. 2011.

- Hay C. The Club and the Drawing-Room Being Pictures of Modern Life: Social, Political, and Professional. London: Robert Hardwicke. 1870.

- Pearce JMS. The legacy and maladies of Jonathan Swift. Hektoen Int. Fall 2019

- Lewis P, Wood N. John Gay and the Scriblerians. London: Vision, 1989.

- Pearce JMS. John Arbuthnot: physician, wit, and creator of John Bull. Hektoen Int. Winter 2020.

- Rumbold Valerie. Scriblerus Club [Scriblerians]. In Dictionary of National Biography, OUP 2008. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/71160

- Pearce JMS. The Lunar Society Legacy. Hektoen International. Summer 2014.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.

Spring 2022 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply