JMS Pearce

Hull, England, United Kingdom

|

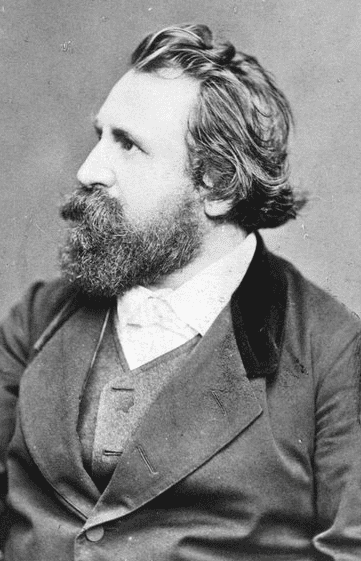

| Fig 1. Theodor Meynert. Photo by Ludwig Angerer. Before 1880. Via Wikimedia. |

Theodor Meynert (1833-1892) (Fig 1) was an eminent if eccentric neuropathologist and psychiatrist. His original work had an impact not just on medicine but on the philosophy of the mind and the “history of materialism.”1 Modern brain research attempts to unravel the intricacies of human brain-mind relationships, much of which was foreshadowed by Meynert’s important anatomical observations and his remarkable foresight into brain mechanisms.2 He gave the first accounts of several neural structures and developed theories correlating neuroanatomical and mental processes.

Meynert3,4,5 was born in Dresden on June 14, 1833. His father was a historian, his mother an opera singer. When he was eight, the family moved to Vienna and the influence of artistic, Bohemian living never quite left him.

As a student he worked with Carl Wedl and the great pathologist Carl von Rokitansky (1804–1878), who stimulated his ideas and future research. After a rambunctious student life,6 he received his MD in 1861. Based on his thesis “Structure and function of the brain and spinal cord and their significance in disease,” he was appointed “Privatdozent” in 1865 and became director of the prosectorium of the State Psychiatric Hospital in Vienna in 1870. Regarded as a prophet of scientific progress, he rapidly published several pioneering discoveries based on his skills as a neuropathologist.6 In 1873, he became Professor of Neurology and Psychiatry in Vienna. His original ideas drew many visitors to Vienna, yet he was considered a poor teacher and his writings are often unclear. Forel, his pupil, related that his department was disorderly and filthy.

The aim of his work was the anatomy and histology of cerebrum and brainstem, the topography and functional relations of the connecting fiber systems. These he exposed using precise anatomical observations. He developed new techniques using thin serial sections stained with carmine or gold with quantitative histological measurements. He sought to relate cortical function to varied cell types and to establish the neural association fibers (radiations of Meynert)7 within the brain. From these he searched for a definable and measurable “substance” for the human psyche. This was later developed by J. W. Papez’s proposed mechanism of emotion.8

Meynert first described the lamination and cellular diversity of the cerebral cortex in 1872. He showed that there were three kinds of nerve fibers comprising what he called the projection, callosal, and association fiber-systems. The cortex carried out the “life of ideas or mental representations” via specific fiber-like pathways that connected the cortex to the rest of the nervous system. When these fiber pathways were damaged, the fabric of the mind would be impaired with consequent mental symptoms.

For instance, he described a case of aphasia in a woman aged twenty-three who had trouble speaking as the “inhibition of verbal expression.”9 She had lost, he said, “memory-images” [Erinnerungsbilder] of the sounds of words. At autopsy he found discolored tissue near the Sylvian fissure that he called the “sound field” [Klangfeld], the cortical area where mental representations of sounds, including speech, were formed. This was very similar to Wernicke’s receptive aphasia.

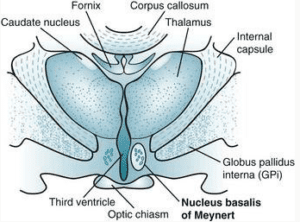

He described a ganglion, a new element in the substantia innominata, Ganglion der Hirnschenkelschlinge.

“. . . a flat extended ganglion that lays below the cerebral peduncular loop, a mass which represents the 2nd stratum of Reil’s Substantia innnominata, or Gratiolet’s Anse pédonculaire . . .”

Albert von Koelliker (1817-1905) called this the nucleus basalis of Meynert (Fig 2); it had cholinergic functions now thought important in memory loss and visual imperception in neurodegenerative diseases. Meynert’s powers of description were not the most lucid, and in 1896 Albert Köelliker renamed the Ansa-ganglion “Meynert’s Basalganglion.”

|

| Fig 2. Nucleus basalis of Meynert. Source. |

Eponymously he is also remembered in Meynert’s bundle, Meynert’s commissure, and the solitary cells of Meynert located in the region of the calcarine fissure in the visual cortex.

In his Diseases of the Forebrain (1884), he described insanity as a disease of the forebrain. In this book he disparaged the idea of mental illness per se, believing its symptomatology was founded on structural brain disease. His work rather than his personality inspired a generation of neurologists including Sachs, Starr, Putnam, van Strumpell, Forel, Flechsig, Wernicke, Arnold Pick, and Freud, who in 1882 was his clinical assistant in Vienna.

Meynert was a small, melancholic man with a massive head, a sprawling bushy beard, and mane-like hair. He showed little interest in students and colleagues, being brusque and at times dismissive; perhaps this reflected his son’s death at the age of seventeen and his wife’s death when young.

He was editor of the Wiener Jahrbücher für Psychiatrie and co-publisher of the Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten (Berlin), and of Vierteljahrsschrift fur Psychiatrie. He was president of the Wiener Verein für Psychiatrie und forensische Psychologie. His portrait appears on a set of Austrian postage stamps issued in 1937. His admirable drawings of the brain remain in the Neurological institute of Vienna. He was also an accomplished poet. Despite high civic honors, he died a rather sad, melancholic figure at Klosterburg on May 31, 1892.

References

- Phelps S. Brain Ways: Meynert, Bachelard and the Material Imagination of the Inner Life. Med Hist. 2016;60(3):388-406. doi:10.1017/mdh.2016.29.

- Seitelberger F. Meynert’s basal nucleus. In: Neurological Eponyms. edited by Peter J. Koehler, George W. Bruyn, John M. S. Pearce. Oxford, New York. OUP 2000, pp. 29-36.

- Mayer C. Obituary in Wiener klinische Wochenschrift, 1933, 46: 738-741.

- Jolly F. “Theodor Meynert”. Arch Psychiat Nervenkr 1892;24:3-7.

- Pearce JMS. The nucleus of Theodor Meynert (1833–1892)). Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 2003: 74, 1358.

- Papez JW. In: Webb Haymaker and Francis Schiller, Eds. The Founders of Neurology. Eds. 2nd edn. Springfield. Charles C Thomas pp. 57-62. 1970.

- Clarke E, and O’Malley CD. The Human Brain and Spinal Cord: A Historical Study. 2nd edn San Francisco, Norman. 1996, pp.432-7, and 602-3.

- Papez JW. A proposed mechanism of emotion, Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry, 1937;38: 725–743.

- Meynert T, Anatomische Begründung gewisser Arten von Sprachstörungen. Österreichische Zeitschrift für praktische Heilkunde 1866; 199–200.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of science and medicine.

Leave a Reply