Ira D. Glick

Danielle Kamis

Stanford, California, United States

Neil Eisenberg

San Francisco, California, United States

|

| With permission of the Int Society of Sport Psychiatry |

Religion has always had a powerful effect on culture. As such, it is surprising that there has been scant literature on the effect of religious beliefs and teachings on participation in sports and the subsequent effect on individual health. The beliefs, guidelines, advice, suggestions, and sermons shared orally and in religious texts have had positive and negative effects on the physical and mental health of men and, perhaps more crucially, women. The Jewish religion is used here to make the argument, but others such as Islam or Christianity could also demonstrate this point.

History

The first half of the Bible depicts the Jewish nation as fierce and warlike. Jews were aggressive, courageous warriors and even strong mercenaries. However, the Jewish problem with sports first arose during the last part of the fourth century BC. Greek athletes embraced nudity, and nudity exposed Jews to ridicule of circumcision, which led to a rather unusual disguise through crude attempts at plastic surgery. Over time, the situation came to the attention of the rabbis, who eventually provoked a crisis by prohibiting participation. Some Jews had built a gymnasium in Jerusalem in the heathen fashion, i.e., nude athletics, a practice which deeply violated the rabbis’ sense of modesty. In addition to circumcision ridicule, the Greeks treated the winners of their sporting events as godlike, which also irritated the rabbis, who felt that this was akin to the worship of “false Gods.”1

From 167 to 160 B.C. the Maccabees revolted and ousted the Seleucid Greeks from the Jewish homeland. Greek athletics were completely banned. Unlike the Jews, the Greeks prioritized the body’s physical esthetic over its role as a “house for the soul.” The Maccabee rabbis would have none of it and they banned sports with a vengeance that endured for the next 1,800 years.2 Being “the People of the Book,” the rabbis scoured the traditional writings and created a rabbinical body of literature that vastly overstated the argument and athletics were strongly prohibited. The argument, however, was so forceful that it survived for centuries, sadly reducing the Greek concept of a sound mind and a sound body to the Jewish view that “if a Jew had a sound mind, God would take care of the rest.”

During the Middle Ages the Jews were subjected to persecution in almost every country they lived in. Throughout this entire time, Jewish communities generally followed strict Rabbinic teachings with little exceptional variation. If, as in the case of Spinoza in the seventeenth century, they strayed from religious orthodoxy, they could be excommunicated and ostracized from the community. This meant that sports were still not part of Jewish life. But interestingly there were some exceptions, in that athletics were not viewed as a monolithic entity. Physical activity was allowed in certain circumstances; the critical factor was whether or not the activity was dangerous.3

Earlier, the brilliant doctor, philosopher, and rabbi Maimonides, born in 1135 in Spain, became the first rabbi to rationalize Jewish law into a body of literature that was understandable and rational.4 But he was not just a rabbi; he was the finest doctor of the day, and actually understood the absolute necessity of physical activity as a prerequisite for good health. His writings, which are the most authoritative commentary on Jewish law ever written, were quite explicit about the necessity of both a sound mind and a sound body.

These and other teachings galvanized individuals from passivity to active participation—and thus, to better mental and physical health. Boxing had been a popular sport amongst the Greeks and Romans, but had virtually become unknown during the Middle Ages, only to resurface in England around the turn of the eighteenth century. Daniel Mendoza, born in 1764 to Spanish and Portuguese Jews, would soon change the face of Jewish athletics. From 1780 until 1790 he revolutionized English boxing, turning it from a staid, boring sport of two men standing their ground and punching each other, into a scientific match of brawn and brains. Boxing changed attitudes towards active participation in sport and fitness to improve health.

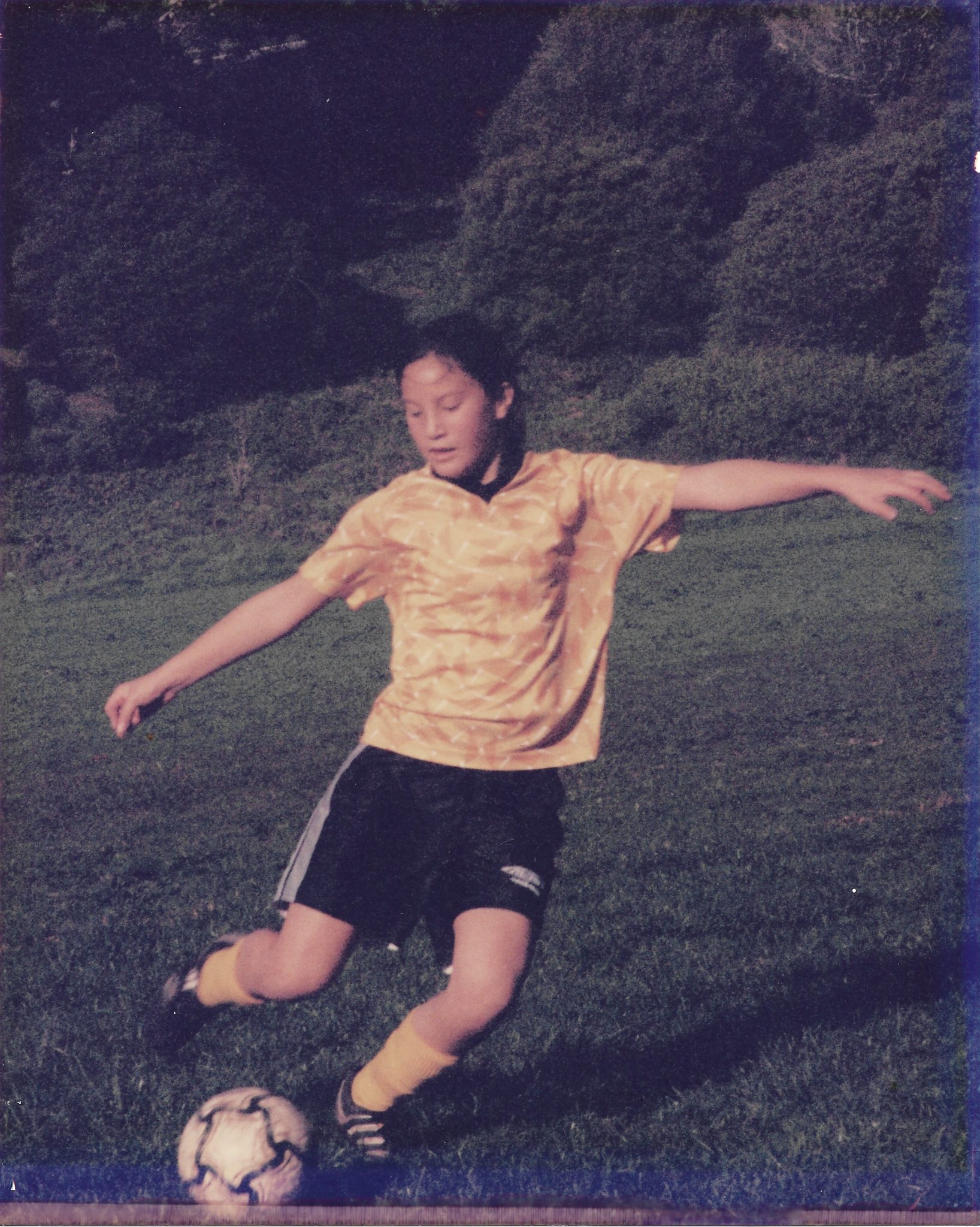

|

| Photo by Ira Glick. |

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, millions of Jews came to the United States. As these Jews were assimilated into the American system of athletics, women were also encouraged to be active and men started to excel in American boxing. The Jewish love of boxing manifested in the immigrant community because boxers were admired for their accomplishments rather than as violating outdated rabbinic restrictions. The next sport was swimming. While it took a long time for Jews to obtain swimming supremacy, the success of Mark Spitz in the Olympics opened another avenue. By 1930, the game of basketball also became known as a Jewish sport. It was probably not an accident that Jewish teenagers were encouraged to participate in basketball as opposed to the more dangerous and violent sport of football. Jewish kids took to both basketball and baseball with a passion, and soon Jewish superstars emerged in both sports.

Women and sports5

Females throughout history have been steered away from competitive athletics. Thankfully, the notion that “competitive athletes with its concomitant tough physical contact is inappropriate” is no longer considered wise advice.5 As mentioned previously for men, but even more so for women, were concerns about modesty. Women were essentially prohibited from competing and denied opportunities to excel in sport. Over time, laws such as Title IX have improved funding and given women the opportunity to flourish as student-athletes. In fact, competitive collegiate women athletes achieve a higher grade point average than the general student body.6,7 Women are now actively encouraged by their families to participate in sports, improving their health and life expectancy. They are active in diverse sports such as fencing, gymnastics, basketball, swimming, track, and wrestling.8

Sports provide physical and mental satisfaction and fulfillment for women athletes. Participation in sport meets psychological needs such as “being accepted as a member of the group” and the drive to maintain cognitive, psychological, and physiological homeostasis in the brain and the body.9,10 There is a feeling that the “mind and the body are in balance.” Women also now make up a majority of physicians in training, gaining equal terrain not just in sport, but professionally. Young women are now encouraged to take an active role in improving their own health and the health of others.

Sports and health10,11

Exercise not only increases mental and physical health but decreases illness. During exercise, brain chemicals increase and memory function improves. Physical activity stimulates neurons in the hippocampus, decreases loss of brain volume, increases synchronized activity in the temporal lobe, and protects against neurodegeneration. There is even good data that regular exercise decreases the risk of some cancers, prevents their recurrence, and delays cancer-related deaths. Participation in athletics also improves mental health, is associated with decreased stress and anxiety, and is an important factor in the treatment of schizophrenia and mood disorders.11

Conclusion

Throughout history, the influence of religion on sports participation has been powerful. The absence of sport had a negative impact on Jewish communities and individual health. In the last 140 years, sports participation has served as a marvelous racial, ethnic, religious, and cultural pathway to improve health, saving and extending lives and enriching the field of medicine.

References

- Ganzfried, Solomno. Code of Jewish Law, Volume I. New York: Rabbis Hebrew Publishing Company, 1961.

- Segal, Eliezer: “Why the Olympic Spirit Lacks a Jewish Neshama.” UCalgary. Last modified September 1, 1987. https://people.ucalgary.ca/~elsegal/Shokel/870901_Olympic.html

- Shurpin, Yehuda: “Are Dangerous Sport Like Football and Wrestling Kosher?” Chabad. Accessed August 25, 2020. https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/4271261/jewish/Are-Dangerous-Sports-Like-Football-and-Wrestling-Kosher.htm

- Brown, Jeremy. “Kidushin 29a – Swimming and Drowning.” Talmudology. Last modified April 8, 2016. http://www.talmudology.com/jeremybrownmdgmailcom/2016/3/23/kiddushin-29a-swimming-and-drowning

- Galily, Yair, Jaim Kaufman, and Ilan Tamir: “She got game?! Women Sport and Society from an Israeli Perspective.” Israel Affiars 21, no. 4 (2015): 559-584.

- Bednarsh, Joe: “Jews in Sports: Something to Think About and Appreciate” Yu Ideas. Last modified January 2020. http://yeshiva.imodules.com/s/1739/images/gid28/editor_documents/Jews_sports_society.pdf?sessionid=e10174e8-3e4c-4dba-b6b6-39667ff211de&cc=1

- Fleming, Kara: “A Comparison of Athletes vs Non Athletes Grade Point Average.” NW Missouri. Accessed August 25, 2020. https://www.nwmissouri.edu/library/researchpapers/2015/Fleming,%20Kara.pdf

- Kamis D, Morgan M: Fencing, ISSP Manual of Sports Psychiatry. New York, Routledge 2018, pp 197-206.

- Glick ID, Kamis D, Stull T: Basketball, ISSP Manual of Sports Psychiatry. New York, Routledge Press, 2018, pp 104-112.

- Stein DJ, Collins M, Daniels W et al: Mind and muscle: The cognitive-affective neuroscience of exercise. CNS Spectrums, 2007; 12:19-22.

- Noordsy DL, Borgess J, Hardy KV: Therapeutic potential of physical exercise in early psychosis. Am J Psychiatry, 2018; 175:209-213.

IRA D. GLICK, M.D., Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, at Stanford University School of Medicine, has an extensive background in research, education, and academic medicine. He was the Senior Science Advisor to the Director of the National Institute of Health (NIMH) from 1986-88. He has written over 200 articles and chapters on academic psychiatric and medical topics. As a leader in the field of Sport Psychiatry, he has written an overview of the field, on psychiatric treatment of elite athletes, and the psychiatric aspects of basketball.

DANIELLE KAMIS, MD, completed her residency at the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Stanford University School of Medicine, where she is now an Adjunct Clinical Assistant Professor. In her collegiate career, she excelled in the sport of fencing at the University of Pennsylvania where she was an All-American, Academic All-Ivy honoree, and competed in the 2013 Maccabiah Games earning a silver medal. She has been published in multiple scientific journals in the field of sports psychiatry and on the role of the female athletes, as well as co-edited the first book of its kind, Manual of Sports Psychiatry.

NEIL EISENBERG, JD, is a San Francisco attorney who specializes in administrative law. At the age of sixteen while serving as the statewide president of a Jewish youth organization in Wisconsin, he attended a national Jewish seminar and received a copy of the Shulchan Aruch (Code of Jewish Law) as a prize for diligence in Jewish studies. Since that time, he has been a lifelong student of Jewish law.

Summer 2021 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply