Glenn Braunstein

Los Angeles, California, United States

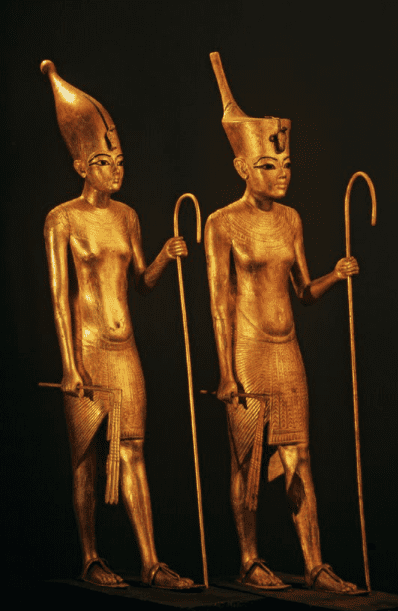

Among the artifacts uncovered in 1922 by the British archeologist Howard Carter from Egypt’s Valley of the Kings tomb of Tutankhamun (~1343-1324 BC) were gilded statues of the young pharaoh in various poses. These statues depict him with androgynous features including wide hips, a sagging belly, and prominent breasts which were felt to represent true gynecomastia rather than excessive mammary fat (pseudogynecomastia) (Figure).1,2 Based on these figures and other images, various authors have suggested that Tutankhamun, who died around age nineteen, may have suffered from Klinefelter syndrome, an adrenal tumor, liver dysfunction from Wilson disease or schistosomiasis, hypopituitarism, or pubertal gynecomastia.3

After examining images of the last four hereditary pharaohs of the Eighteenth Egyptian Dynasty (~1550-1295 BC), Bernadine Paulshock, MD, pointed out that Tutankhamun’s father, Akhenaten, his putative brother, Smenkhkare, and his paternal grandfather, Amenhotep III, all exhibited enlarged, feminine-appearing breasts. Dr. Paulshock raised the possibility that the feminine physique or gynecomastia shown in the various images represented familial gynecomastia, possibly due to an androgen receptor (AR) defect.3

Several mutations in the AR gene, located on the X-chromosome, have been described as causing absent or reduced responsiveness to testosterone and other androgens. Loss of androgen antagonism of estrogens leads to feminization. Complete inactivation of the AR receptor results in the syndrome of testicular feminization, in which genetic males look like females, while less deleterious mutations cause partial or mild androgen insensitivity. Persons with the mildest form may have gynecomastia alone and retain fertility.4 Being X-linked abnormalities, AR mutations are transmitted through the maternal line. Dr. Paulshock hypothesized that this was possible as there was much consanguinity among the members of the Eighteenth Dynasty.3

Braverman and colleagues found depictions of breast enlargement in other male members of the Eighteenth Dynasty, including in Tutankhamun’s possible paternal great grandfather Thutmose IV, and in his great-great grandfather Amenhotep II, suggesting that familial gynecomastia was present for at least five generations.5 They proposed that one possible explanation for the feminization of the men without obvious impairment of fertility is aromatase excess syndrome, which is predominately transmitted as an autosomal dominant disorder. First described by Hemsell, et al. in 1977, this syndrome results in a gain-of-function dysregulation of the widely distributed aromatase enzyme, due to a variety of different mutations in the aromatase gene.6,7 Aromatase catalyzes the conversion of testosterone to estradiol and the adrenal androgen androstenedione to estrone. The excessive estrogen levels result in prepubertal gynecomastia, rapid linear growth, and advanced bone age during childhood leading to premature fusion of the epiphysis of the long bones and relative short stature as adults. Females with the syndrome may exhibit markedly increased breast growth (macromastia), short stature as adults, and irregular menses. Of interest, Braverman et al. showed a relief of Akhenaten with his wife Nefertiti (not Tutankhamun’s mother) and three of their daughters. One of the daughters, Meketaten, estimated to be between the ages of five and seven years old has prominent breasts and wide hips, suggesting that she had isosexual precocious puberty, which would be compatible with the aromatase excess syndrome.5 However, imaging studies of Tutankhamun’s bones showed incomplete fusion of the epiphyseal plates of the long bones compatible with his chronological age, rather than the premature fusion expected with the aromatase excess syndrome.8,9

Using molecular analysis, the foremost Egyptian archeologist and former Minister of State for Antiquities, Egypt Affairs, Zahi Hawass, PhD, and co-workers published an extensive evaluation of the ancestry and pathology of Tutankhamun and members of his family.9 This study together with archeological evidence allowed them to establish that Tutankhamun fathered the two female fetuses found in his tomb, and that his father was most likely Akhenaten. They noted that Tutankamun had malaria and Kohler disease II (juvenile aseptic bone necrosis of the left second and third metatarsals); the latter along with congenital equinovarus deformity undoubtedly resulted in his needing to use the many walking sticks found in his tomb to ambulate.9 Although this study essentially ruled out that Tutankamun had Klinefelter syndrome, since he fathered two girl fetuses, it did not examine the possibility that he and the other male members of his family had either mild androgen insensitivity syndrome or aromatase excess syndrome. Both of these possibilities could be explored through additional DNA analysis.

Of course, the above discussion about the possible medical causes of the feminized appearance of the males of the Eighteenth Dynasty is all speculation based on the images of the pharaohs and their relatives. We have no autopsy data to substantiate that the men actually had gynecomastia or other manifestations of either excessive aromatase activity or a mild androgen receptor defect. Howard Carter did not describe the breast tissue during his examination of Tutankhamun, and in their study of the remains of Tutuankhamun in 1968, Harrison and Abdalla noted that the sternum and anterior aspect of the ribs had been removed and could not be evaluated.8 The putative enlarged breasts in Akhenaten could not be demonstrated because his remains were composed of a mummified skeleton.9

In the absence of anatomical evidence of gynecomastia or genetic analysis demonstrating mutations in the aromatase or androgen receptor genes, we must consider the alternative hypothesis favored by many experts of Egypt’s Eighteenth Dynasty including Professor Hawass: the figures of the pharaohs are symbolic representations and not true likenesses. Akhenaten broke with his predecessors who subscribed to polytheism, and proclaimed the sun god (Aten) to be the only true deity. He moved the capital from Thebes to Akhet-aten (“Horizon of the Sun-disc”; currently known as Amarna), and instituted a number of reforms including in art (Amarna style). It is possible that Akhenaten decreed that his images be androgynous to emphasize his representing all of his subjects, men and women, or to assume some of the characteristics of the earlier Nile gods that had prominent breasts representing fertility.1, 3 However, it is difficult to reconcile this explanation with the fact that statues and other images of his paternal predecessors also showed breast enlargement. Also, Tutankhamun, whose original name was Tutankhaten broke with Akhenaten’s monotheism, changed his name, moved the capital back to Thebes, and restored polytheism. Conceivably his rejection of his father’s changes may well have included Akhenaten’s demands for a symbolic representation of the pharaohs’ appearance rather than a realistic depiction of their true physique.

The discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb sparked world-wide interest in Egyptian archeology. In the ensuing years, we have learned a great deal about the pharaohs and other members of the royal families of Eighteenth Dynasty. As over 3,300 years have elapsed since the end of the dynasty, it is not surprising that many details about the pharaohs’ physical appearance and health remain shrouded in mystery. Among them is the question whether the physical likenesses of Tutankhamun and his paternal ancestors are true representations of their appearance or merely symbolic artistic license.

References

- Hawass Z, Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs. Washington, D.C., National Geographic, 2005.

- Braunstein, GD. Gynecomastia. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:1229-1237.

- Paulshock BZ, Tutankhamun and his brothers. Familial gynecomastia in the Eighteenth Dynasty. JAMA. 1980; 244:160-164.

- Hornig NC, Holterhus P-M. Molecular basis of androgen insensitivity syndromes. Molecular Cellular Endocrinol. 2021; https://doi.org/10.1016?j.mce.2020.111146

- Braverman IM, Redford DB, Mackowiak PA. Akhenaten and the strange physiques of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:556-560.

- Hemsell DL, Edman CD, Marks JF, Siiteri PK, MacDonald PC. Massive extraglandular aromatization of plasma androstenedione resulting in feminization of a prepubertal boy. J. Clin Invest. 1977; 60:455-464.

- Shozu M, Fukami M, Ogata T. Understanding the pathological manifestations of aromatase excess syndrome: lessons for clinical diagnosis. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2014; 9:397-409.

- Harrison RG, Abdalla AB. The remains of Tutankhamun. Antiquity. 1972; 46:8-14.

- Hawass Z, Gad YZ, Ismail S, Khairat R, Fathalla D, Hasan N, Ahmed A, Elleithy H, Ball M, Gaballah F, Wasef S, Fateen M, Amer H, Gostner P, Selim A, Zik A, Pusch CM. Ancestry and pathology in King Tutankhamun’s family. JAMA. 2021; 303:638-647.

GLENN D. BRAUNSTEIN, MD, is Professor of Medicine at Cedars-Sinai, Professor Emeritus at UCLA, former Chair of the Department of Medicine at Cedars-Sinai (1986-2012), and Vice-Chair of the Department of Medicine at UCLA (1986-2012). He received his M.D. degree from UCSF School of Medicine, and his postgraduate training at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, Harvard Medical School, the National Institutes of Health, and Harbor General Hospital-UCLA, and is Board Certified in internal medicine and the subspecialty of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism. He has published over 385 peer-reviewed manuscripts, monographs, chapters, and reviews in the fields of reproductive endocrinology and thyroid cancer.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 1 – Winter 2022

Leave a Reply