Ku Ezriq Raif bin Ku Besry

Perlis, Malaysia

|

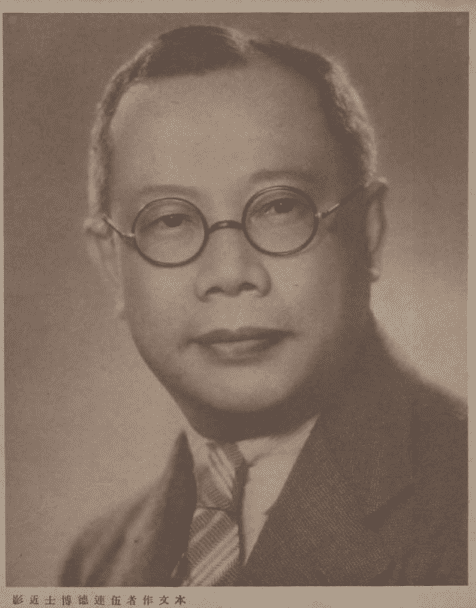

| Dr. Wu Lien-teh 1935. Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain. |

The work of Wu Lien-teh in controlling the 1910 Manchurian Plague has been celebrated as “a milestone in the systematic practice of epidemiological principles in disease control.” The cloth face mask he developed, “the principal means of personal protection”1 during the outbreak, was a significant contribution to the world of medicine during his time and remains so in the modern day.

Wu Lien-teh was born on March 10, 1879, the fourth son of an immigrant family in the state of Penang in pre-independence Malaya, a place known as the “Pearl of the Orient.” He would one day receive the sobriquet “The Plague Doctor”2 for the achievements of a lifetime of persistence. This persistence was evident early in his life. In 1893, seven years after enrolling at the Penang Free School, Wu sat for his first examination for the Queen’s Scholarship but would require three more attempts before he was finally awarded the coveted prize.3

From this first achievement, his educational journey took off. He received many distinctions, such as becoming the first Straits student to attain the status of “Exhibitioner”4 after being awarded a scholarship in natural science at Emmanuel College in Cambridge.5 He also became a Foundation Scholar, which covered his training fees at St. Mary’s Hospital where he would go on to receive the Special Prize in Clinical Surgery (1901), the Kerslake Scholarship in Pathology (1901), and the Cheadle Gold Medal for Clinical Medicine (1902).6

In addition to academic acclaim, he was also a humanitarian whose dedication to helping others was inspired by his colleague Lim Boon Keng, who instilled “the need for devoting some time to social service among the people.”7 Wu played a “prominent part in the social service work, and tried hard to introduce reforms among the people, such as girls’ education, removal of the queue, pigtails for men, campaign against gambling and opium smoking, formation of literary clubs and promotion of healthy physical exercises among boys and girls.”8

His major humanitarian effort was in the anti-opium movement in Malaya where he gave his “heart and soul to the anti-opium campaign” and asked the British government “to take such steps as may be necessary for bringing it to a speedy close.”9 Wu founded the Anti-Opium Association and organized a nationwide anti-opium conference in 1906 that was attended by nearly 3000 people.10,11

Despite his academic and medical acclaim and humanitarian efforts, Wu was not highly regarded in his birthplace, particularly by the authorities of Penang who supported the profitable opium trade.11 The discontent escalated and a raid was staged on Wu’s home, where he was convicted and fined for possessing one ounce of tincture of opium.11

With these tensions, Wu found himself at a crossroads in his life, writing:

“Should I remain on the inhospitable shores of my birthplace where neither government nor friends seemed to need me, or should I accept the invitation, so opportunely offered, to render useful service to China where, at least, I would not be misrepresented and where I might find a fertile soil for promoting the scientific and health work which I had taken such pains to acquire before and since graduation.”12

Unsurprisingly, Wu decided to accept this invitation to the post of Vice-Director of the Imperial Medical College in Tianjin, as offered by the Grand Councilor of the Chinese government in Peking, General Yuan Shih-Kai.13 During his post, Wu learned of a deadly epidemic in Harbin, where authorities required the help of an expert in bacteriology to “proceed to that region to investigate the cause and to suppress it, if possible.”14

When Wu and his assistant arrived in Harbin, the situation was dire. Dead bodies littered the streets, and there were only two doctors and five dressers addressing a disease that had killed 99.9% of its victims.15

Dr. Gérald Mesny, a renowned French professor at Peiyang Medical College in Tiajin, insisted on being in charge of operations because of his prior experience in tackling bubonic plague. However, when Wu conducted a preliminary post-mortem examination of a patient who had died of the disease, he found evidence of the more virulent and airborne pneumonic plague, and not the vector-borne bubonic plague as suspected by Mesny.11,16

With this revelation, Wu developed a personal protection tool that was vital in tackling the airborne form of plague: a face mask layered with gauze and cotton to filter the air.17 Wu then initiated the strategy of using buildings such as warehouses and train cars as isolation facilities, and promoted the use of face masks to protect oneself and others.11

However, Mesny, in a display of colonial arrogance and racism, dismissed Wu’s strategy. In his autobiography, Wu narrated this dismissal using the third-person point of view:

“Dr. Wu was seated in a large padded armchair, trying to smile away their differences. The Frenchman was excited, and kept on walking to and fro in the heated room. Suddenly, unable to contain himself any longer, he faced Dr. Wu, raised both his arms in a threatening manner, and with bulging eyes cried out ‘You, you Chinaman, how dare you laugh at me and contradict your superior?’”18

Mesny himself died six days after this episode, having contracted plague from the patients he had examined, unmasked.19

|

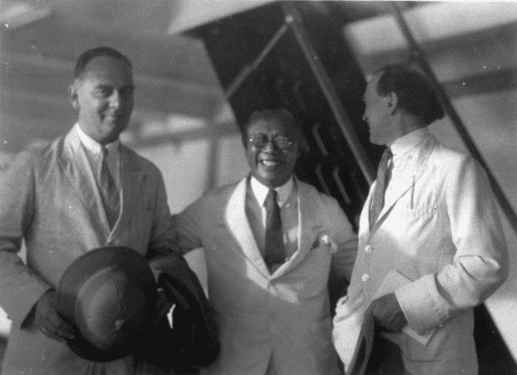

| Group photo of Messrs. Jan van L., Dr. Wu Lien Teh and Professor De Langen, Tandjong Priok, Batavia, c. 1928. Collectie Stichting Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen/Public Domain. |

After Mesny’s death, the use of cloth face masks became widely accepted.20 Eventually, the extensive use of this tool for personal protection resulted in control of the 1910 Manchurian Plague, a feat that earned Wu a nomination for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1935.21

However, two years later, Wu returned to Malaya after his Shanghai home was invaded and burned during the Japanese occupation of China.15 Wu’s life in his birthplace was also rife with hardship, particularly during the Japanese occupation of Malaya. Not only was he was kidnapped and held ransom by guerrilla fighters of the Malayan Communist Party, he was also accused by the Japanese of assisting the resistance movement. His life was spared because he was the attending physician to a Japanese officer in Malaya.11

Despite all of this, Wu persevered and achieved more acclaim, such as becoming the first director of the National Quarantine Service, receiving awards from the Czar of Russia and the President of France, and being awarded honorary degrees by many overseas universities such as the University of Tokyo, the University of Hong Kong, and Peking University.15

There are many parallels and lessons from Wu’s life that are pertinent to the modern era. When faced with marginalization in his birthplace, Wu made a decision to move to China, which defined his career and led to him being the first Nobel Prize-nominated Malayan.21 Today that decision and his work have impacted the way in which the world has addressed the Covid-19 pandemic. Without his development and popularization of the cloth face mask, which is widely believed to have been the progenitor of the N95 mask,19 the world would be facing worse spread of the virus.

Furthermore, when faced with colonial racism and Mesny’s dismissal of his findings and recommendations, Wu persevered. Today, although almost a century has passed since Wu’s lifetime, anti-Asian racism remains rampant. This discrimination must be stopped so that the true issue—the virus itself—can be dealt with swiftly and efficiently.

Notes

- Goh, L. G., T. M. Ho, and K. H. Phua. “Wisdom and western science: the work of Dr Wu Lien-Teh.” Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health 1, no. 1 (1987): 99-109.

- Wu, Lien-Tê. Plague fighter: The autobiography of a modern Chinese physician. Areca Books, 2014.

- Tan, C. L. Live free: In the spirit of serving. Singapore: The Old Frees’ Association (2016): 166.

- Penang School. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1898): 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- Wu, 2014, p. 182.

- Wu, 2014, p. 193.

- Wu, 2014, p. 221.

- Wu, 2014, p. 232.

- Wu, 2014, p. 236.

- Cooray, Francis, and Salma Nasution Khoo. Redoubtable Reformer: The Life and Times of Cheah Cheng Lim. Areca Books, 2015.

- Lee, Kam Hing, Danny Tze-ken Wong, Tak Ming Ho, and Ng Kwan Hoong. “Dr Wu Lien-teh: modernising post-1911 China’s public health service.” Singapore medical journal 55, no. 2 (2014): 99. doi:10.11622/smedj.2014025.

- Wu, 2014, pp. 244–245.

- Wu, 2014, p. 244.

- Wu, 2014, pp. 279–280.

- Obituary: Wu Lien-Teh. The Lancet 1, no. 7119 (1960): 341. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(60)90277-4.

- Ma, Zhongliang, and Yanli Li. “Dr. Wu Lien Teh, plague fighter and father of the Chinese public health system.” Protein & cell 7, no. 3 (2016): 157-158.

- Wu, L. “A treatise on pneumonic plague. League of Nations.” Health Organisation (1926).

- Wu, Lien-teh, and Litt MAMDMPH. “Plague Fighter. The Autobiography of a Modern Chinese Physician.” Plague Fighter. The Autobiography of a Modern Chinese Physician. (1959).

- Wilson, Mark. “The untold origin story of the N95 mask.” Fast Company (2020).

- Lynteris, Christos. “Plague masks: the visual emergence of anti-epidemic personal protection equipment.” Medical anthropology 37, no. 6 (2018): 442-457. doi:10.1080/01459740.2017.1423072.

- Wu, Lien-Teh. The Nomination Database for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 1901–1953. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media AB 2020. 1 April 2020. https://www.nobelprize.org/nomination/archive/show.php?id=11153. Accessed September 12, 2021.

KU EZRIQ RAIF BIN KU BESRY has a diploma in English from the Sultan Idris Education University and is currently pursuing a BS in education at the University of Technology Malaysia. He has a couple of poems published in the Anak Sastra literary journal. Moreover, he uses humor throughout his work and hopes for a better tomorrow for everyone.

Summer 2021 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply