JMS Pearce

Hull, England, UK

|

| Fig 1. Johnson’s Dictionary [photo: author’s copy] |

After the first dictionary of English words (Robert Cawdrey’s A Table Alphabetical… 1604) many dictionaries aimed to provide typical spelling, meaning, and often pronunciation, etymology, synonyms, and quotations. A New English Dictionary was an important advance reflecting everyday language compiled by the first professional lexicographer, John Kersey the Younger, in 1702. The most famous was Samuel Johnson’s A dictionary of the English language, 1755 (Fig 1) containing two volumes and 118,000 illustrative quotations, which aimed to replace Dictionarium Britannicum of Nathan Bailey (1730). Johnson defined a Lexicographer as “a writer of dictionaries; a harmless drudge, that busies himself in tracing the original, and detailing the signification of words.”

As the English language expanded and incorporated words and phrases from distant lands, there was an absence of any comprehensive dictionary. In the nineteenth century, The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) published by Oxford University Press (OUP) filled that gap. The 2005 version contains approximately 301,100 main entries and 2,412,400 usage quotations. It is the principal historical dictionary of the English language. Many more specialized dictionaries with diverse lexical foci were to follow.1 In 1828, Noah Webster published his two-volume masterpiece, titled An American Dictionary of the English Language, now Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary.

The OED began in 1857, and by 1884 was published in unbound fascicles as A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles; Founded Mainly on the Materials Collected by The Philological Society. It started as the works of the Philological Society of London. The main early contributors included philologists and lexicographers, notably Richard Chenevix Trench, Herbert Coleridge, and Frederick Furnivall. In the 1870s, Furnival secured the assistance of James Augustus Henry Murray (1837–1915), a Scottish teacher at Hawick Grammar School, lexicographer, and philologist.

|

| Fig 2. Sir James Murray. Via Wikimedia. |

Sir James Augustus Henry Murray (1837-1915)

If ever a lexicographer merited the adjective iconic, it must surely be James Augustus Henry Murray . . .

Peter Gilliver (OUP blog 2013)

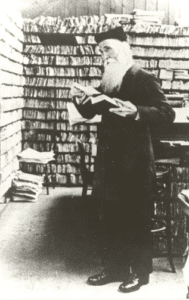

Murray (Figs 2 & 3) was born in Denholm near Hawick in the southern uplands of Teviotdale. He was the eldest son of a clothier, proud to be a hardy, independent Borderer. Remarkably, his schooling ended at the age of fourteen. He worked in a London bank but in his spare time became an accomplished self-taught linguist and etymologist.a He was appointed in 1869 to the Council of the Philological Society, which was filled with frock-coated members. The august Murray stood out as a long-bearded, “unconventionally attired man in corduroy trousers, with a tie of pink ribbon, having the most strikingly twinkling brown eyes . . .” 2 He was belatedly knighted in 1908.

Oxford English Dictionary

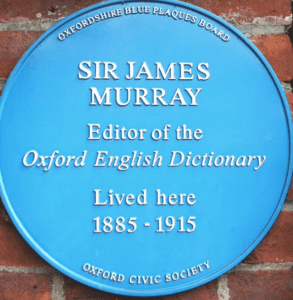

On 26 April 1878, Murray was invited to meet the delegates of the Oxford University Press, who appointed him editor from 1879 until his death from pleurisy in 1915.3

From the start, the massive scale of the project was evident and the help of volunteer amanuenses to find and copy words and quotations was required. Murray had a prodigious capacity for hard work. In 1879, he launched the great “Appeal to the English-speaking and English-reading public,” which ultimately attracted millions of quotation slips. Each volunteer was assigned particular books, copying passages illustrating word usage onto quotation slips. He asked readers to report “as many quotations as you can for ordinary words” and for words that were “rare, obsolete, old-fashioned, new, peculiar or used in a peculiar way.”2 Murray had moved to Mill Hill School London in 1864, where he taught English. A year later he built a corrugated iron shed on the grounds called the scriptorium to accommodate his assistants. They collected the numerous slips each carrying quotations, which illustrated the everyday use of the words they sought to define. Many sent in quotations from anything they happened to read; more than a thousand people contributed to the first edition.

|

| Fig 3. Sir James Murray blue plaque. Photo by Owen Massey McKnight. Via Flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0 |

The first section, A–Ant, appeared in 1884, in the first unbound edition The Oxford English Dictionary. In that year the sheer size of his collection forced him to move to larger premises on the Banbury Road, Oxford where he erected a second scriptorium. It was republished as the first full edition in 1928 in ten bound volumes containing more than 15,500 pages. With such a comprehensive coverage it was not until 1989 with several supplements that the second edition was published in twenty volumes.

One of the major contributors was the infamous William Chester Minor (vide infra).

After the republication of 1928, Robert Burchfield was hired in 1957, with help from the grammarian and lexicographer Charles Talbut Onions, to edit the second supplement; before its completion twenty-nine years had elapsed. William Craigie, a lexicographer, was the third editor of the Dictionary. Onions was the fourth editor, who also co-edited the 1933 Supplement with Craigie.4

Burchfield included contemporary language, and expanded the supplement to include a wealth of new words from science and technology, as well as popular culture and colloquial speech. Loanwords from other English-speaking countries were included. Such was its growth that in 1963 it was clear that a computerized full text was needed. By 1989, the New Oxford English Dictionary project had successfully combined the original text with Burchfield’s supplement into a single unified dictionary. A print version of the second edition was published in 1989, a third (electronic) edition is in preparation.

John Simpson in 1976 was appointed by Robert Burchfield to work on the Supplement and with Edmund Weiner became Co-Editor of the Second Edition in 1989. He was appointed Chief Editor in 1993. In 2000, the OED Online with quarterly updates became available to subscribers. It took more than 120 typists, fifty-five proofreaders, and millions of keystrokes to digitize the entire contents.

|

| Fig 4. William Minor, The surgeon of Crowthorne. Source. |

The OED currently contains an unsurpassed guide to the meaning, history, and pronunciation of 600,000 words and over three million quotations—past and present—from across the English-speaking world.5 Words that became obsolete remain as historical records. Abridged versions are in widespread use: The Concise Oxford Dictionary (240,000 words) edited by the brothers FG and HW Fowler; The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary revised by Onions; and The Pocket Oxford Dictionary of Current English. A magnifying lens accompanies a single-volume Compact Edition with its minute page size.

The dictionary’s singular scholarship is exemplified by comments such as “An incomparable monument of scholarship, one of the wonders of our age” (Nature), “A cathedral of words and a great British creation” (Robert McCrum, Observer), and “the supreme completed achievement in all lexicography” (Encyclopaedia Britannica).1

*****

Dr. William Chester Minor

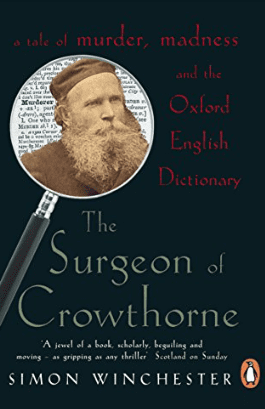

The Yale Medicine Magazine describes how William C. Minor MD (1835-1920) (Fig 4) left his mark: he developed schizophrenia, killed a man, and became a brilliant linguistic scholar while in an asylum for the insane.

Minor was born in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), the son of church missionaries from New England. Having graduated, he served as a Union Army surgeon. He then worked in New York, but spent much time with prostitutes. By 1867, his erratic behavior led to his removal to a remote post and in 1868, he was diagnosed as delusional and was admitted to the government’s St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for the Insane in Washington, D.C., and officially retired from the U.S. Army. Having been released, in 1871 he boarded a boat bound for London and lived at 41, Tenison Street, Lambeth where prostitutes abounded. But his paranoid delusions persisted.

In a fascinating book Simon Winchester relates how on February 17, 1872, at two o’clock in the morning outside the Lion brewery, (Fig 5) he fatally shot a man named George Merrett, who the deluded Minor believed had broken into his room.6 He was tried before Lord Chief Justice Bovill and, under the McNaghten rulesb of the 1840s, was deemed insane. He was therefore not hanged but sent to the Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum in the village of Crowthorne, Berkshire on 17 April 1872, where he remained for thirty-eight years. 7

|

| Fig 5. “Lion Brewery, where Dr Minor shot George Merritt [sic], A Brewery stoker.” from Strand magazine 1915. Wikimedia. |

He was not judged dangerous and was given comfortable quarters and a library. Through his booksellers Minor learned of Murray’s call for volunteers to contribute to the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary. To this laborious task he devoted most of his life. From 1882 over two decades he focused mainly on sixteenth and seventeenth-century texts, making notes on more than 12,000 slips, mailing them to Murray’s scriptorium. Often tormented by delusional figures at night, he barricaded his door with furniture to prevent attempted entry. Aside from these nightly terrors, he was mostly rational by day and proved to be one of the OED’s most prolific volunteers. Minor also sent money to Eliza, the widow of the man he had killed, and she visited him in Broadmoor bringing him books.

Minor kept secret his hospital address, but many years later Murray learned of Minor’s background only when he visited him in January 1891.6 Murray, though astonished that he lived in a lunatic asylum, praised his contributions:

The supreme position is . . . certainly held by Dr. W. C. Minor of Broadmoor, who during the past two years has sent in no less than 12,000 quots [sic]. . . . So enormous have been Dr. Minor’s contributions during the past 17 or 18 years, that we could easily illustrate the last 4 centuries from his quotations alone.

Minor’s condition deteriorated and in 1902, beset by psychotic, sexual delusions, he cut off his penis. After Murray campaigned on his behalf, the Home Secretary, Winston Churchill, eventually released him for deportation in 1910. He was dispatched to the USA to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital where they diagnosed dementia praecox (schizophrenia). He was finally transferred in 1919 to a Retreat for the Elderly Insane in Hartford, Connecticut, where he died aged eighty-five in 1920.

End Notes

- Papers of Sir James Augustus Henry Murray (1837-1915), editor of the Oxford English Dictionary are at Oxford, Bodleian Library.

- “Every man is to be presumed to be sane, and . . . that to establish a defence on the ground of insanity, it must be clearly proved that, at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of mind, and not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong.”

References

- Read AW, Dictionary. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/dictionary

- Murray KM. Elizabeth. Caught in the Web of Words: James Murray and the Oxford English Dictionary. Yale University Press. 1977 p. 178

- Gilliver, Peter. The making of the Oxford English Dictionary Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Ogilvie S. Words of the World: A Global History of the Oxford English Dictionary. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Winchester S. The Meaning of Everything: The Story of the Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2003.

- Winchester S. The Surgeon of Crowthorne: A Tale of Murder, Madness and the Love of Words. UK: Viking 1998. (published in America as The Professor and the Madman) [A film in 2019, The Professor and the Madman featured Mel Gibson and Sean Penn]

- Church Hayden. The strange case of Dr. Minor. The Strand Magazine 1915; pp. 252-257.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of science and medicine.

Spring 2021 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply