Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

|

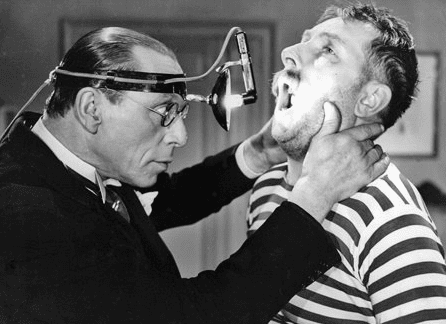

| Louis Jouvet and André Dalibert in Knock, by Guy Lefranc (1951) |

“The man who feels well is actually sick and doesn’t know it.”

—Dr. Knock

Jules Romains (1885-1972), author of the play Knock, or the Triumph of Medicine, was a novelist, poet, essayist, playwright, and short story writer. He was considered one of the best writers of his generation.1 This paper presents a detailed summary of Knock2 and speculates on Romains’ intentions in writing this play.

In Act I, Dr. Knock discusses with Dr. Paraplaid the rural medical practice that he has bought from Dr. Paraplaid sight unseen, in the little village of St. Maurice. The village is full of healthy people, who occasionally visit the doctor for a consultation. He sees ten patients a week. There are no repeat visits, no regular patients. The patients pay the doctor once a year, in September. Knock mentions that he wrote his medical thesis on “Imaginary States of Health,” and tells Paraplaid that “the man who feels well is actually sick and doesn’t know it.” He inquires as to the presence of secret societies, cults, or very religious people in St. Maurice, then tells Paraplaid to come back in three months to see how his “method” has changed the old doctor’s practice.

In Act II, Knock gets the town crier to announce that he will be offering free consultations on Monday mornings (which is also the market day). He then visits the town schoolmaster, pretends to be surprised that Dr. Paraplaid and the teacher, M. Bernard, have not worked together to educate the people of the village about hygiene and health. He flatters the schoolmaster into agreeing to deliver a lecture to the public on the dangers of typhoid.

Knock visits the town’s only pharmacist, feigns surprise at how little the pharmacist earns, and how seldom Dr. Paraplaid coordinated his prescription writing with the pharmacist. He tells the pharmacist, M. Mousquet, that from now on all the inhabitants of the district will be our “regular clients” and that the pharmacist will treble his income.

In his first free consultation, he convinces a rich farm owner that as a child, forty years ago, she fell off a ladder and that is the cause of her back pain (not her strenuous physical work on the farm). He explains, with a lot of medically flavored doubletalk, the origin of her problems in the spinal cord and the high price for curing such a chronic problem. She asks for an alternative (cheaper) treatment and he recommends total bed rest in a dark room, no conversations, and no solid food but lots of Vichy water during a week of observation. It is clear that she will not attempt such a week of deprivation and will take the high-priced treatment instead.

An older noblewoman comes to consult, hoping to offer an example to the people of the district so that they will also visit the doctor. Knock gets her to confess to some long-standing insomnia, which Dr. Paraplaid had minimized. Knock wonders if it could not be “the neuroglia continually and violently attacking the grey matter. It’s like a giant spider chewing and destroying your brain.” This, luckily, could be cured by radioactivity over a period of two to three years, with daily home visits by the doctor. There is a French expression “avoir une araignée au plafond,” meaning “to have a spider on the ceiling,” (the ceiling being one’s head). In English we would say “to have a screw loose.”

The next consultation is made by two drunk village louts, who treat the visit as a joke. Knock spitefully tells one of them that his alcohol intake has damaged his heart and kidneys. The laughter and winking stop. The young man asks if there is any treatment possible. No, “it is scarcely worth the effort.”

In Act III the village’s only hotel has been converted into a sort of medical center. Dr. Paraplaid has come to see what changes Knock has made in the three months in St. Maurice. He still has a day of free consultations. Otherwise, the rich patients pay for their visits, but the poor do not pay. Dr. Paraplaid wonders, “If I used your method would I not feel any qualms?” Knock tells him, “That’s up to you.” Dr. Paraplaid: “Isn’t the welfare of the patient being considered after the welfare of the doctor?” Knock replies, “I’m only concerned about the welfare of medicine.”

There ensues a brief discussion about Dr. Paraplaid coming back, and Knock taking over Paraplaid’s practice in Lyon. The people will not hear of it. Dr. Paraplaid says, “The people here prefer charlatanism to honesty.” He is told by the hotel owner that “a real doctor” would not have let so many people die during the influenza epidemic.

Knock suggests to Paraplaid that he needs to stay in the hotel/hospital for twenty-four hour of rest. Paraplaid admits that he has noted some problems lately. Knock tells him that they will discuss it later. He also says that he cannot help diagnosing everyone he sees. “Indeed, for a while now, I’ve avoided looking at myself in the mirror.”

What to make of Dr. Knock’s “method?” His dissertation was on “Imaginary States of Health” and we hear him say, “Health is only a word, and there would be no problem eliminating it from our vocabulary . . . I only know people who are more or less affected by more or less numerous diseases progressing more or less rapidly. Naturally, if you tell them they’re well, they’ll believe you. But you are deceiving them.”

An opposing view has been expressed by Hadler:3

“To be well is not to be free of symptoms . . . at least not continuously or for long. We all experience routine problems of body and mind . . .Whatever we do, we are challenged to cope with these predicaments of living and life. To be well is to be able to cope with morbid episodes – and coping may not be easy. It can be thwarted by the intensity of the illness or by complicating factors such as medicalization. When the person with the problem interprets the symptoms as a medical disease, an illness for which medical treatment could or should be sought, that is medicalization . . . Medicalization imposes a scientific idiom of distress on common sense.”

The medicalization that Knock proposes is an “astonishing anticipation of our medical epoch.” Medical anxiety provides people with a meaning for their existence: “I’m sick, therefore I am.”4 Knock influences people to live a “medical existence,” which becomes the focus of their lives. It is most profitable to keep them sick, but not to let them die.5

The period we live in is marked by “disease mongering,” that is, convincing doctors and the public at large that there are certain “diseases” in the population that need to be diagnosed and treated. The problem is that these “diseases” are invented by the pharmaceutical industry and then are accepted as real entities by many physicians.6 To increase sales of medications and diagnostic tests, a few techniques7 may be used:

§ By changing the normal threshold values of clinical or laboratory tests, risk factors (hypertension, hypercholesterolemia) become definite “diseases.”

§ Expanding definitions of disease by expanding diagnostic criteria will result in pre-disease “diseases” (such as pre-diabetes).

§ New diseases may be created by grouping symptoms into syndromes (chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia).

§ Finally, there may be pathologization of normal conditions (menopause, age-related osteoporosis, shyness).

Pharmaceutical firms may also finance or donate to patient associations, further legitimizing a created diagnosis.8 The interwar period in Europe is thought to be a period in which people transferred their faith and confidence from religion to medicine.9 This idea is also suggested in Franz Kafka’s A Country Doctor.10 The result in Knock is a “medical religion”11 and Knock is either an apostle of a new religion12 or a “health messiah.”13 A visit to the hotel-turned-medical center is like a “medical pilgrimage.”14

Knock, in establishing his medical domain, uses military metaphors. He tells the pharmacist that the adoption of his theory is like producing an “armed nation” and “a doctor who cannot rely on a first-class pharmacist is like a general going to war without artillery.” (Mousquet is French for “musket.) Near the end of the play, Knock shows Dr. Paraplaid a map of his “medical penetration,” that is, how he has made patients of a great number of inhabitants of the province.15

In 1922 Mussolini and his fascists marched on Rome and took over the government of Italy. Knock was published and first performed in 1923. That year Adolf Hitler and his small Nazi party attempted, in the “Beer-Hall Putsch,” to take over the government of Bavaria. In 1917 a revolution installed a totalitarian communist government in Russia.

Ousselin16 states that Knock is not the light, frivolous play that one may mistake it for. He believes that it ranks with Animal Farm, 1984, and Brave New World, allegories or stories of totalitarian states. Knock comes to St. Maurice with a determination to spread his dogma. He is a charismatic leader. The schoolmaster is recruited as his Minister of Propaganda. Knock had asked Dr. Paraplaid about secret societies, cults, or highly religious people in the province. He knows that “a proselytizing mass movement must break down all existing group ties if it is to win a considerable following.”17 So much the better for the would-be dictator if such group ties are already absent. Also, a dictator must win and hold “the utmost loyalty of a group of able lieutenants . . . They must . . . submit wholly to the will of the leader . . . and glory in this submission.”18 These “lieutenants” are M. Bernard the schoolmaster, M. Mousquet the pharmacist, and Mme. Rémy the hotel/medical center owner. We know that at least one of Knock’s patients—the older, aristocratic lady—is ready to be as “submissive as a little dog.”19 Knock tells Dr. Paraplaid that when he looks out his window, the province transforms into a kind of heaven, “of which I am the continual creator.”20

What about eliminating the word “health” from the vocabulary? Orwell, in 1984, tells us the purpose of Newspeak (the new language being introduced) is to provide a way to express the “world-view” of the ruling party, but also “to make all other modes of thought impossible.” Heretical thoughts “should be literally unthinkable.”21 One film version of Knock (1951) uses dictatorial imagery to great advantage. When Knock comes to the hotel/hospital to make rounds, his assistants and nurses fall in behind him to form a pseudo-military parade. In the patient rooms, as in the classrooms and offices of twentieth century dictatorships, there is a framed photo of the “leader” (Knock in this case) on the wall.

The play ends with Dr. Paraplaid more or less convinced that Knock knows something about Paraplaid’s health. Knock is also convinced that he himself is sick. Thus, the fanatical originator and vector of Knockism is infected with his disease as well.

References

- Jacques Guicharnaud, ed. 1967. Anthology of 20th Century French Theater. Paris: Paris Book Center Inc.

- Jules Romains. 1964. Knock ou Le Triomphe de la Médecine. Paris: Gallimard.

- Nortin Hadler. 2004. The Last Well Person: How to Stay Well Despite the Health-Care System. Quebec: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Luc Boulanger. “Knock ou le Triomphe de la Médecine: Le pouvoir thérapeutique de l’art.” La Presse (Montreal). 14 September 2019.

- NA. “Jules Romains (1885-1972), Knock.” ND etudes-litteraires.com

- Pierre Biron. “Le Dr Knock après neuf décennies. Le prophétisme de Jules Romains.” ND. [email protected]

- Collectif Formindep. “Le disease mongering à l’heure de la medecine ‘personnalisée’.” Les Tribunes de la Santé 2, no.55: (2017): 37-44.

- JC George. “Disease mongering ou stratégie de Knock.” De la Médecine Générale, February 2009. Docteurdu16.blogspot.com

- Boulanger, “Le pouvoir thérapeutique.”

- Franz Kafka. 1996. A Country Doctor In The Metamorphosis and Other Stories. New York: Barnes and Noble.

- Edward Ousselin. “Knock: de guérisseur à dictator.” Dalhousie French Studies 71, (2005):91-102.

- etudes-litteraires.

- Iain Bamforth. “Knock: A Study in Medical Cynicism.” Medical humanities 28, no. 1 (2002): 14-18.

- Ousselin, “Knock: de guérisseur.”

- Ousselin, “Knock: de guérisseur.”

- Ousselin, “Knock: de guérisseur.”

- Eric Hoffer. The True Believer. New York: Harper and Row, 1966.

- Hoffer, “True Believer.”

- Romains, “Knock.”

- Romains, “Knock.”

- George Orwell. 1984. New York: The New American Library, Inc, 1983.

HOWARD FISCHER, MD, was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan. He is very interested in the ways that physicians are portrayed in fiction.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 3– Summer 2021

Spring 2021 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply