Nicolás Robles

Badajoz, Spain

|

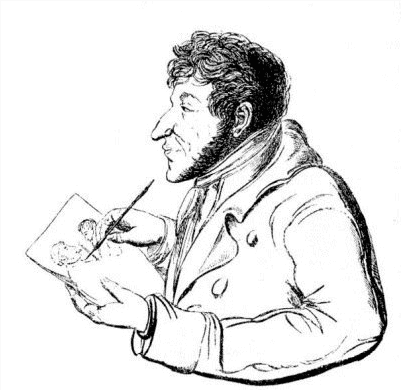

| Figure 1. Hoffmann’s drawing of himself, riding on Tomcat Murr and fighting “Prussian bureaucracy.” From Klaus Günzel: Die deutschen Romantiker. Artemis, Zürich 1995, ISBN 3-7608-1119-1. Via Wikimedia. Public domain. |

Ich bin das, was ich scheine, und scheine das nicht, was ich bin, mir selbst ein unerklärlich Rätsel, bin ich entzweit mit meinem Ich!

I am what I seem and do not seem what I am, an inexplicable mystery to myself, am I at odds with myself!

– E.T.A. Hoffmann, Die Elixiere des Teufels

Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann was a Romantic author of fantasy and horror, a composer, music critic, draftsman, and caricaturist, also a jurist. Known better by his pen name, E. T. A. Hoffmann, he changed his third baptismal name around 1813 from Wilhelm to Amadeus in homage to Mozart. His maternal and paternal ancestors were also jurists. His father, Christoph Ludwig Hoffmann, was a barrister in Königsberg, East Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia), and also a poet and amateur musician who played the viola da gamba.

He was born on January 24, 1776. His parents separated in 1778, his father going to Insterburg with his elder son, while Ernst’s mother stayed in Königsberg with her relatives, two aunts and their brother, all unmarried. Between 1781 and 1792 he attended the Lutheran school, where he made good progress in classics. Taught to draw by a teacher named Saemann, he also learned counterpoint from a Polish organist named Podbieski. In 1794 he fell in love with Dora Hatt, a married woman to whom he had given music lessons. She was ten years older and in 1795 gave birth to her sixth child. In February 1796, her family protested his romantic attentions, and he was employed as a clerk for his uncle, who lived in Glogau. In the summer of 1798 the uncle was promoted to a court in Berlin, and the three moved there in August. Now Hoffmann first attempted to promote himself as a composer, writing an operetta called Die Maske and sending a copy to Queen Luise of Prussia. While waiting for a response, he passed his third round of exams—the Assessorenexamen for the Prussian Administration—and left for Posen (now Poznań).

|

| Figure 2. Hoffmann’s cartoon of himself. Source. Public domain. |

From June 1800 to 1803, he worked in the Prussian provinces of Greater Poland and Masovia. For the first time he lived without the supervision of his family, who thought he had become “dissolute.” His stay at Posen was compromised after Carnival on Shrove Tuesday 1802, when caricatures of military officers were distributed at a ball. It was immediately deduced that he had drawn them, and complaints were made to authorities in Berlin, who “promoted” Hoffmann to Płock in New East Prussia, where he moved with his wife, Mischa. In 1804, he obtained a post at Warsaw, where he assimilated well into Polish society. But on 28 November 1806 Napoleon Bonaparte’s troops captured Warsaw and the Prussian bureaucrats lost their jobs.

This was the beginning of troubled times. Hoffmann had decided not to seek further employment, but to become an artist. While his wife and their two-year-old daughter Cäcilia moved to Posen in 1807, he tried to gain a foothold in Berlin but nobody took notice of his compositions. Finally, in autumn 1808, he became Kapellmeister at the Bamberg Theater and moved there with his wife only, their daughter Cäcilia having already died. He failed as music director, his theatrical compositions brought in no money, but he received an offer to write music reviews for the Leipziger Allgemeine, having published there his story “Ritter Gluck.” From 1810 Hoffmann was employed by the Bamberg Theater as assistant manager, dramaturge, and decorative painter. He also gave private music lessons and fell deeply and embarrassingly in love with a young vocal student. He was then offered and accepted the position of music director with Joseph Secondas in the Dresden and Leipzig performing opera company but had a falling out fell with him as early as 1814. After Prussia’s victory over Napoleon, Hoffmann returned to the Prussian civil service in Berlin, though not with a salary but only a fee.

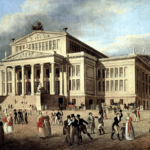

He had by then earned a reputation as a writer. The publication of fantasy pieces in Callot’s Manner (1814/1815), especially the fairy tale “Der Goldene Topf (The golden pot)” was a success, but his novels Die Elixiere des Teufels (The Elixirs of the Devil) and Night Pieces were failures. Instead, he became a sought-after writer for paperback and almanac retellings, which kept him afloat financially. He was particularly proud that his opera Undine, premiered at the National Theater in Berlin in 1816, but his applications for various Kapellmeister posts were all rejected. In that year Hoffmann was appointed judge of the Kammergericht, the chamber court, which came with a fixed salary.

|

| Figure 3. Berlin: Königliches Schauspielhaus (Royal Theatre), currently known as Berliner Konzerthaus. Painting: The Schauspielhaus, Anonym, 1825. Rights: Konzerthaus Berlin Archiv. Source. |

Beginning in 1819, Hoffmann was involved with legal disputes, while also fighting ill health. He developed progressive paralysis, first attributed to syphilis and alcohol abuse,1 starting in his legs and quickly spreading to his arms, so that by January 1822 he could no longer write. Speech was lost, breathing affected, but mental abilities were preserved. On February 4, 1822, the royal Prussian State Minister suggested the imposition of disciplinary measures against him. By then his disease was already well advanced. Confined to a chair, he could only dictate his defense. He dictated to his wife or a secretary a few more stories, including “Des Vetter’s corner window.” He died from respiratory paralysis on June 25, 1822, in his apartment on Taubenstrasse in Berlin at the age of forty-six.

In one of his tales he wrote:

Immer gewichtiger und gewichtiger drückt die zentnerschwere Last Deine Brust — immer mehr und mehr zehrt jeder Atemzug die Lüftchen weg, die im engen Raum noch auf- und niederwallten

The heavy load presses your chest ever heavier and heavier — more and more every breath wears away the air that was still billowing up and down in the narrow space.

– E.T.A. Hoffmann, Der Goldene Topf

Hoffmann most likely died from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (motor neuron disease), a degenerative disease of the motor nervous system.2 The disease had not yet been identified as such until Charcot described it several years later.3 The paralysis started in his feet and spread to his arms so that he could no longer write and finally affected his speech and respiratory system, which is typical of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, although a more rapidly fatal form may begin with the mouth. Mental abilities typically are preserved until the very end, and without ventilators and artificial nutrition, the disease would have been rapidly fatal.

Und wenn sich nun der, den du tief unter dir glaubtest, nicht deiner annimmt, so stirbst du zuletzt eines elendiglichen Todes . . .

And if the one you deeply believed does not take care of you, you will ultimately die a miserable death . . .

– E.T.A. Hoffmann, Lebensansichten des Katers Murr

References

- Ernst Bäumler, Amors vergifteter Pfeil: Kulturgeschichte einer verschwiegenen Krankheit, 1997, S. 259, zitiert nach Anja Schonlau Syphilis in der Literatur: über Ästhetik, Moral, Genie und Medizin (1880–2000), Würzburg, Königshausen und Neumann 2005, S. 80

- A. Neumayr. E.T.A. Hoffmann – Georg Trakl – Anton P. Tschechow im Spiegel der Medizin. Ibera.Verlag European University Press. Wien.2014

- A Compton. The 150th anniversary of the first depiction of the lesions of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988; 51:1249-1252

NICOLÁS ROBERTO ROBLES is professor of Nephrology at University of Extremadura.

Spring 2021 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply