Tamas F. Molnar

Katalin Aknai

Hungary

|

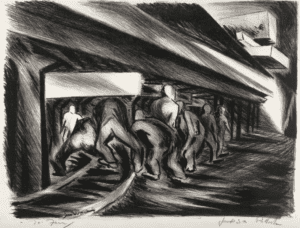

| Jackson Pollock, Miners, ca. 1934-1938, lithograph on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase, 1966.68. |

To this very day, malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) remains a serious oncologic, public health, and industrial challenge, a fatal disease in which standard chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy has done little to increase the chance of survival.1-6 While the role of asbestos exposure in the pathogenesis of the disease is seemingly well established, other industrial factors require far more detailed observational and experimental exploration. Since the 1970s trace metals, including copper, have been high on the list of suspected elemental oncogenes.6 Strikingly, the ambiguous role of copper in tumor signaling is a regularly reappearing question.7

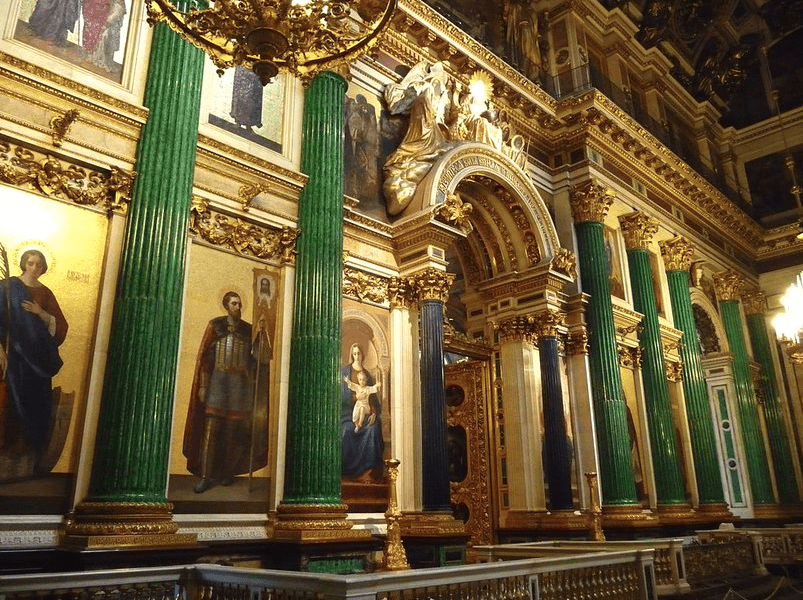

Vast data pools based on national and international public and industrial health surveys offer sources regarding the identification of etiological factors. To ignore, however, sources derived from the humanities and arts would deprive us of useful information. We offer here the story of malachite, a semiprecious stone (copper carbonate hydroxide mineral), whose origin spotlights the copper mining that took place in the Ural mountains of the Russian empire during the nineteenth century. The oncologist, pulmonologist, or thoracic surgeon with an eye for the early unorthodox reports of possible malignancies may discover etiologic clues to copper-miner’s lung, pneumoconiosis, cancer, and even MPM.8

Malachite miners are portrayed as the main characters in the tales of the last century penned by Russian writer and ethnographer Pavel Bazhov.9 His collection of fairy tales, including The Malachite Box, are based on Ural folklore and were later translated into English. There are four tales referencing consumptive lung diseases specifically related to mining. The diseases run a different course from what was typical of tuberculosis during this era. The protagonist in the Tale of the Queen of the Copper Mountains was a young man, but the disease of the malachite miners was already visible on his face. The other man was older and was haggard by the hard work. It seemed that his eyes and face were covered by green ash, the dust of the malachite. He coughed desperately, as if suffocating. The next tale, titled Stone Flower, spotlights Prokopitch, also a miner who “got a fit of cough, nearly choked, as he became very sickish in those years.” Sergei Prokofiev composed a ballet entitled The Tale of the Stone Flower based on this tale. The relatively slowly progressing lung disease he suffered from is different from that afflicting the beautiful girls in the Fountain of the Hobgoblin. Here we read how: “this girl became the wife of Ilia. But not for long. She came from the great distant, a place where the marbles are hewed. That was the reason why Ilia never had seen the girl before. Everybody knows, that those are the most beautiful girls, but the boy who marries one of them will become a widow quite soon. These girls work with the stones from their early childhood and they quickly waste away.” Interestingly, the lack of cough and shortness of breath support the theory of a rapidly progressing malignancy. Levontiiy, the copper miner protagonist of the last tale, Treasure of the Golden River, “became green, like the mildew, wilted and dwindled away, and he vainly was sent out to the open air to work, but it did not help . . .”

|

| Malachite and Lapis Lazuli Columns in the Saint Isaac’s Cathedral, Saint Petersburg (Russia). Photo by user GraceKelly, 2010. Via Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 3.0 |

These seemingly magical stories are beyond fairy tales. What we can recognize here is the clinical course of occupational thoracic malignancies. To understand these diseases, their etiology, and their clinical course requires developing a tunnel of knowledge, rather like the miners carving into the soil depicted in the 1934 lithography of Jackson Pollock, one of the greatest American painters of the twentieth century. Humanities, arts, and literature are thoughtfully presented here, to support the work and efforts of the thoracic surgeon, the pulmonologist, and the basic science worker in a common effort to understand the cause of thoracic malignancies and develop effective measures to prevent and treat these dread diseases.

Reference List

- Sidhu, C., Louw, A., Brims, F. et al. Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: an Update for Pulmonologists. Curr Pulmonol Rep 2019; 8, 40–9.

- Ricciardi S, Cardillo G, Zirafa CC, et al. Surgery for malignant pleural mesothelioma: an international guidelines review. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(Suppl 2):S285-S292.

- Faccioli E, Bellini A, Mammana M, Monaci N, Schiavon M, Rea F. Extrapleural pneumonectomies for pleural mesothelioma. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2020;14(1):67-79.

- Zucali PA. Target therapy: new drugs or new combinations of drugs in malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(Suppl 2):S311-S321.

- de Gooijer CJ, Borm FJ, Scherpereel A, Baas P. Immunotherapy in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Front Oncol. 2020;10:187.

- J. R. Dixon, D. B. Lowe, D. E. Richards,L. J. Cralley,and H. E. Stokinger The Role of Trace Metals in Chemical Carcinogenesis: Asbestos Cancers, Cancer Research 1970; 30: 1068-74.

- Andrew Crowe, Connie Jackaman, Katie M. Beddoes, Belinda Ricciardo, Delia J. Nelson Rapid Copper Acquisition by Developing Murine Mesothelioma: Decreasing Bioavailable Copper Slows Tumor Growth, Normalizes Vessels and Promotes T Cell Infiltration PLOSOne August 27, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073684

- R Chen , L Wei, H Huang Mortality from lung cancer among copper miners Br J Ind Med 1993;50(6):505-9.

- Hurst, Rebecca: Digging deep: the enchanted underground in Pavel Bazhov’s 1939 collection of magic tales, The Malachite Casket. PhD Thesis, University of Manchester, 2018, https://www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/files/110263750/FULL_TEXT.PDF

Note:

The citations are translated from the original Russian through Hungarian by Tamas F Molnar. English translations:

- Bazhov, Pavel. The Malachite Casket. Fredonia Books, 2002. (also translated as The Malachite Box)

- Bazhov, Pavel. The Mistress of the Copper Mountain. Folk tales from the Ural. Publisher unknown. 1974.

- Bazhov, Pavel Petrovich The Mistress of the Copper Mountain and Other Tales. Tehnosphera, 1992.

TAMAS F. MOLNAR is an academic thoracic surgeon with extensive teaching and research experience in the medical humanities. He is professor of surgery at the University of Pécs, Hungary.

KATALIN AKNAI is an art historian with an academic background and a particular interest in modern and contemporary arts. She is assistant professor at the Faculty of Humanities, University of Pécs, and senior research fellow at the Research Centre for Humanities, Budapest, Hungary.

Winter 2021 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply