|

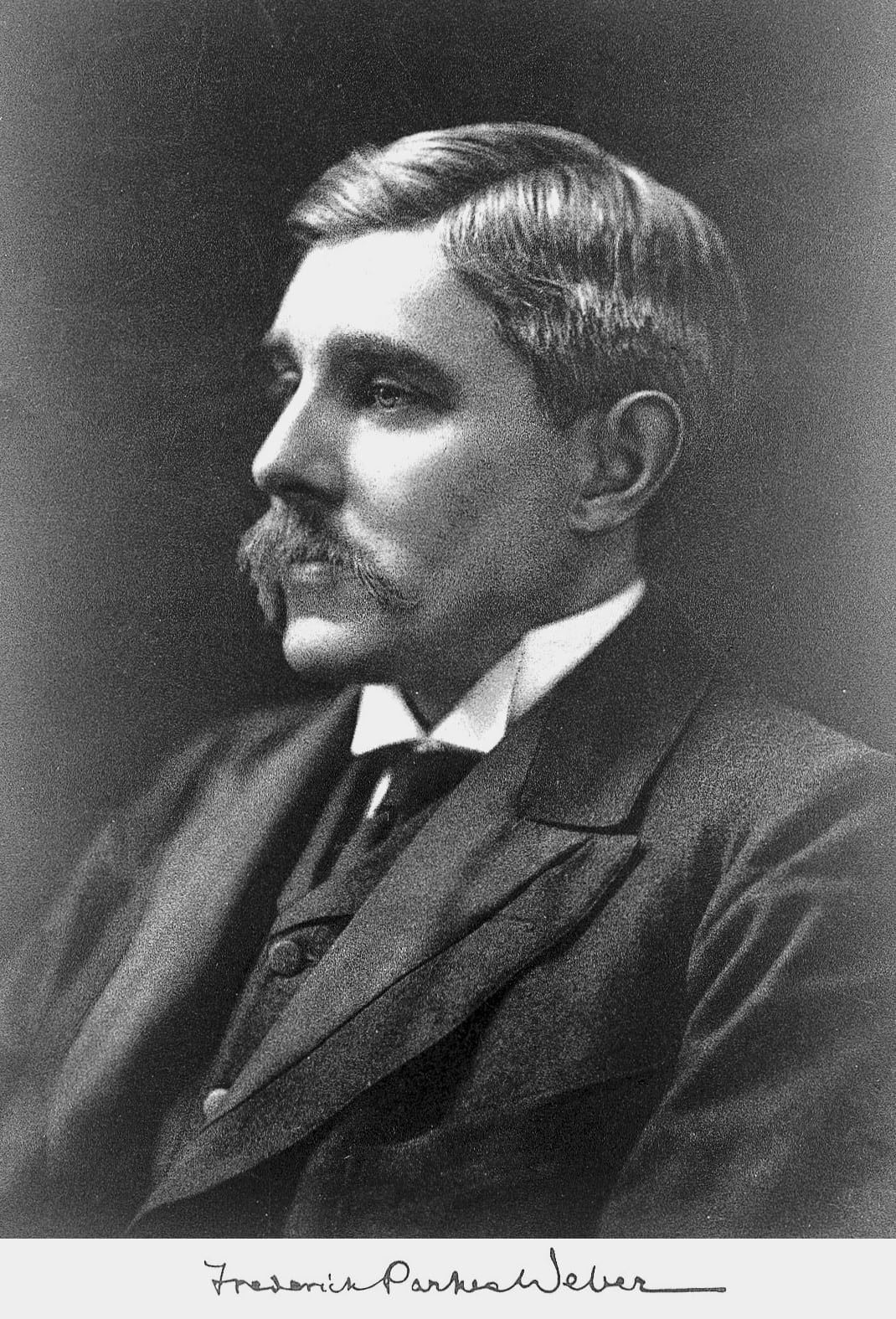

| Portrait of F. Parkes Weber. Published by Adolf Eckstein’s Verlag Berlin, c. 1913, probably for Anton Mansch. Wikimedia. |

If you spend all your time seeing patients, you are not likely to become famous. Renown and power are more likely to go to the “pretending physicians,”1 the species that can be seen on television, in the newspapers, and among those who spend their lives telling others what to do and how to manage their patients.

Exceptions have occasionally occurred. One such exception seems to have been Frederick Parkes Weber. It is difficult to learn much about his nonmedical life, but he wrote over 1,200 articles and contributed to more than twenty books about patients he had seen. He specialized in rare and familial diseases as well as in unusual clinical features, and he has several important illnesses named after him.2-5

The important ones are Rendu-Osler-Weber disease (hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia), Sturge-Weber syndrome (hemangiectatic nevus of the face and sometimes the meninges), and Weber-Christian disease (relapsing febrile nodular panniculitis). But there is also Weber-Klippel syndrome (hemangiectatic hypertrophy of the limbs), Vaquez-Osler-Weber disease (polycythemia vera with splenomegaly), and Weber-Cockayne syndrome (familial recurrent bullous eruption of the hands and feet).2

His father, Hermann Weber, had come from Germany in his youth, became physician to Queen Victoria, and was knighted. Parkes Weber himself graduated in medicine from St. Bartholomew’s medical school in 1889 and continued his medical education in Paris and Vienna. On returning to London he served in resident posts at St. Bartholomew’s and Brompton Hospitals.3 He then practiced medicine in several hospitals, because in those days private consulting physicians had multiple such honorary appointments. He saw patients at the German Hospital in Queen’s Square, at several chest or tuberculosis hospitals, and probably also at the London Metropolitan Hospital. He had an active practice and lived until the age of ninety-nine, dying in 1962.

In that year Victor McKusick wrote an article about him that cannot be improved upon, listing his many articles and books.2 He described how Parkes Weber was particularly interested in unusual clinical presentations, and in particular in familial or hereditary diseases. These are listed in the article as renal glycosuria, Sjogren’s syndrome, familial cirrhosis, gynecomastia, green or blue urine, pigmentation of the mucosae, changes in the fingernails, neurofibromatosis, vicarious menstruation, progressive lipodystrophy, primary amyloidosis, Pickwickian syndrome, hypertension due to tumors of the adrenal medulla, and several others.2 To complete the list were added several books, including Rare Diseases and Debatable Subjects and its sequel Further Rare Diseases.

In Park Weber’s obituary it was mentioned that he was a man of intellectual alertness with an intense interest in clinical detail, an amazing memory, and a clear and emphatic speech. A kindly and modest man, he would attend clinical meetings, and when a certain case was shown he reminded the audience that he or someone else had shown exactly the same condition fifteen years ago—and would give the exact reference. He was a scholar-physician, erudite, gentle, and eager to give of his unusual knowledge. His curiosity was never failing, and perhaps this was the secret of his longevity.3

Also writing at that time, the Archives of Internal Medicine’s distinguished editor William Bean referred to his many achievements and thought that his passing from the scene removed one of the last great generalists and one of the world’s leading connoisseur of medical esoterica. He concluded that he was a clinician of distinction, a consultant of renown, of dignity, and of most impressive character.4 According to a tribute in the Lancet, he was beloved by his patients whom he treated with grave courtesy and listened intently to everything they had to say. “After consulting with the doctor he always went back to the patient and said something kind and encouraging. He shook him earnestly by the hand and said goodbye in a way that made him feel he was really sorry to go. He was loved not only by patients but by everybody who came into contact with him. He had a great charm. His face was always radiant with interest and goodwill. He liked everybody and was interested in everything.”4

Parkes Weber lived in the days of “médicine lente,” when consulting physicians spent more time with patients, delving deeply into all the details of the present, past, and family history. It was a time when a complete physical examination took at least thirty minutes and sometimes more. And from there, the way to proceed took experience and wisdom, common sense and strategic thinking, qualities which Parks Weber exhibited to a full extent.

Further reading

- Dunea G. Pretending physicians and other new breeds. BMJ 1995;310:65 (Jan7)

- McKusick V.A. Frederick Parkes Weber. JAMA 1963; 183:45 (Jan5).

- British Medical Journal 1962; 1: 1630, (June 9)

- Bean W: Parks Weber. Arch.Intern. Med 1963;111: 545, (May)

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, Editor-in-Chief

Summer 2020 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply