Amy DeMatt

Greensburg, Pennsylvania, United States

“Desperation, weakness, vulnerability – these things will always be exploited. You need to protect the weak, ring-fence them, with something far stronger than empathy.”

— Zadie Smith

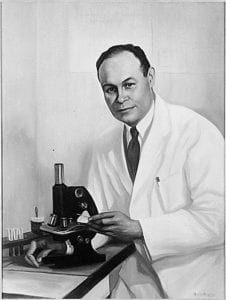

Charles R. Drew, “Father of the Blood Bank,” as depicted by Betsy Graves Reyneau. The portrait hangs at the National Portrait Gallery, and, as described by the Gallery, serves as a “visual rebuttal to racism.” Portrait of Charles R. Drew, painted by Betsy Graves Reyneau, 1950, National Portrait Gallery. Via Wikimedia.

What if, instead of simply practicing empathy, you could literally become a part of someone else? What if you could join a part of your body with another person’s to help that person overcome sickness, even bring that person from the brink of death to life? What if you could do all this and remain healthy yourself, revitalizing another through the abundance provided by science? Charles Richard Drew, the “Father of the Blood Bank,” imagined such revival and made it a reality. What makes his story extraordinary is that he was stymied in his efforts to save lives. The enemy was disappointingly pathetic: the limiting beliefs of racial segregation, widely held during Drew’s lifetime. Drew’s story illustrates that we need something stronger than empathy to protect the weak; we need to innovate. By showing what we are capable of, we teach others how to lead.

In spite of a modest upbringing, Charles Drew showed leadership at a young age. He grew up in Washington, D.C. His father was a carpet-layer. His mother was a graduate of the Miner Normal school, an African-American teacher training school, although she never worked as a teacher.1 At age twelve, Drew became a paper boy. By age thirteen, he had six boys working for him.2 He was not a brilliant student in his early years, but he was a gifted athlete.3 Besides earning varsity letters in four sports, he was voted best athlete, most popular student, and the student who had done the most for his school. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he was recruited by Amherst College in Massachusetts in 1922 on football and track and field scholarships.4 Being the team’s best athlete, he would have been the natural choice to be captain of the football team, but such a way of thinking would not account for segregation. Drew was passed over as captain his senior year. This is surprising, because Drew was so athletically gifted that even today, his reputation as an athlete is better known among some than his reputation as a scientific pioneer in blood preservation.5 Drew’s experience in athletics not only taught him the value of hard work but also provided him with access to resources. To earn money for medical school, he took a job as athletic director and instructor of biology and chemistry at Morgan College in Baltimore. Ever the achiever, Drew’s coaching led his team to become serious collegiate competitors.6

Drew ultimately attended McGill University College of Medicine in Montreal, Canada.7 There he won the annual scholarship prize in neuroanatomy and was elected to Alpha Omega Alpha, the medical honor society. He won the J. Francis Williams Prize in medicine after beating five students in an exam competition. He graduated second in his class of 137.8 In 1933 he became an intern at Montreal Hospital and worked with John Beattie, a bacteriology professor, on treating shock with fluid replacement.9 He wanted to continue with transfusion therapy at the Mayo Clinic, but racial prejudices interfered. Not one to be daunted, he joined the Howard University College of Medicine, first as a pathology instructor, then as a surgical instructor, and then as chief surgical resident at Freedman’s Hospital.10

In 1938 Drew won a scholarship to train at Presbyterian Hospital in New York under the preeminent surgeon Allen Whipple. Whipple assigned him to work under John Scudder, who had been granted funding to set up an experimental blood bank. This assignment meant that unlike his white peers, Drew could not interact directly with patients. The slight proved fateful. Scudder described Drew as a “brilliant pupil.” Drew subsequently became the first African-American to earn his doctorate from Columbia Medical School. Just after graduation, Scudder tapped Drew to help with a program for blood storage and preservation.11

Drew’s research focused on variables that affected the shelf life of stored blood. These variables included anticoagulants, preservatives, and the shapes and temperatures of storage containers.12 Drew discovered the separated plasma component of blood could be used to replace fluids and treat shock, and blood could be preserved for longer periods of time without refrigeration. The blood also would not deteriorate when agitated during transport and was less likely to transmit disease. The plasma, which had been separated from the blood by use of a centrifuge and sedimentation, also had the advantage that it could be injected into veins, muscles, and skin in large doses.13

Drew’s accomplishments led him to head the “Blood for Britain” project during World War II.14 The project saved lives of wounded soldiers by providing supplies of blood for medical care of the wounded. As part of the project, plasma was pooled from a collection of eight bottles using strict anti-contamination techniques.15 Samples were cultured to determine if they harbored bacteria.16 Merthiolate, a compound made of mercury and sodium, was added to batches of blood products that were tested weekly. Batches were then transferred to shipping containers and diluted with sterile saline. A final sample was taken for bacterial testing before the containers were sealed and packed for shipping to England. In total, the “Blood for Britain” program collected 14,566 donated units and shipped 5,000 liters of plasma saline to England.17 The program became a model to mass-produce dried plasma while Drew was the assistant director of the Red Cross.

Drew also established the use of bloodmobiles, mobile donation trucks with refrigerators used for collecting and storing blood. Ironically, the Red Cross program prohibited donations of blood from African Americans. The reason was not “biologically convincing,” but “commonly recognized as psychologically important in America,” that it was “not advisable” to mix Negro and Caucasian blood.18 The Red Cross later amended the program to accept donations but upheld the racial segregation of blood. Drew described blood segregation as “unscientific and insulting to African-Americans.”19 He ultimately resigned from the Red Cross because he objected to the practice of segregating blood.20

Drew’s focus then changed. In October of 1941, he became the head of the department and chief of surgery at Freedman’s Hospital. There his goal was “to train young African-American surgeons who would meet the most rigorous standards in any surgical specialty” and “place them in strategic positions throughout the country where they could, in turn, nurture the tradition of excellence.”21 In a January 24, 1947 letter to Mrs. J.F. Bates, a Fort Worth schoolteacher, Drew wrote:

So much of our energy is spent in overcoming the constricting environment in which we live that little energy is left for creating new ideas of things. Whenever, however, one breaks out of this rather high-walled prison of the ‘Negro problem’ by virtue of some worthwhile contribution, not only is he himself allowed more freedom, but part of the wall crumbles. And so it should be that the aim of every student in science is to knock down at least one or two bricks of that wall by his own accomplishment.22

In April of 1950, Drew was driving to Andrew Memorial Clinic in Tuskegee, Alabama to deliver a lecture. He fell asleep while driving. His car ran off the road and rolled over. Drew suffered extensive injuries. He was taken to Alamance Hospital, a poor white hospital, but his injuries were so severe he could not be saved. There is a rumor that Charles Richard Drew died because the white hospital would not transfuse blood for him. This rumor is false, however.23 Drew was given a transfusion. His injuries were simply too severe to salvage his life. Thus, Drew appears to have accomplished his goal to change attitudes towards blood segregation and transfusion, even if the achievement of those goals did not save his life.

Charles Richard Drew’s pioneering efforts in science and blood preservation served as a testament to the strides he made by persisting in his scientific efforts, even when the outside world refused to conform to his standards. For this, he is best remembered as a courageous innovator in the war against bloody segregation. What are we to make of the life story of Charles Richard Drew? Perhaps it is that life exists abundantly, both figuratively and literally, for those who care to do more than empathize. One must innovate. One must avail oneself of resources at hand, to find or forge a path for advancement

Endnotes

- Pilgrim, David. “The Truth About the Death of Charles Drew.” Ferris.edu. https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/question/2004/june.htm (accessed January 2, 2020).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. “Charles R. Drew, The Charles R. Drew Papers.” Nlm.nih.gov. https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/spotlight/bg/feature/biographical (accessed January 6, 2020).

- DLWStoryteller.com. “Dr. Charles Drew – The Blood Man.” dlwstoryteller.com. https://dlwstoryteller.com/day-4-dr-charles-r-drew-the-blood-man (accessed January 3, 2020).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- “Father of the Blood Bank.” ACS.org. https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/african-americans-in-sciences/charles-richard-drew.html (accessed January 3, 2020).

- US National Library of Medicine. ”Charles R. Drew, The Charles R. Drew Papers.” Nlm.nih.gov. https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/spotlight/bg/feature/biographical (accessed January 6, 2020).

- “Father of the Blood Bank.”

- Id.

- Id.

- Id.

- Id.

- Id.

- Id.

- Pilgrim.

- “Father of the Blood Bank.”

- Id.

- Id.

- Giaimo, Carla. “In the Early 1940s, the Red Cross Banned Black Blood Donors.” June 14, 2016. Atlasobscura.com. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/in-the-early-1940s-the-red-cross-banned-black-blood-donors (accessed January 13, 2020).

- Id.

- Lovett, Haley. “Dr. Charles Richard Drew, Pioneer of Mass Blood Collection and Supervisor of the First Red Cross Blood Donor Service.” Findingdulcinea.com. https://www.findingdulcinea.com/features/profiles/d/charles-drew.html (accessed January 2, 2020).

- “Father of the Blood Bank.”

- U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Pilgrim.

AMY MEARS DEMATT, J.D., is the winner of the Dodd Award from Washington and Lee University for her written work in philosophy. She went on to earn her law degree from W&L. She manages the courts for the Tenth Judicial District of Pennsylvania and continues to read and write avidly.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

Leave a Reply