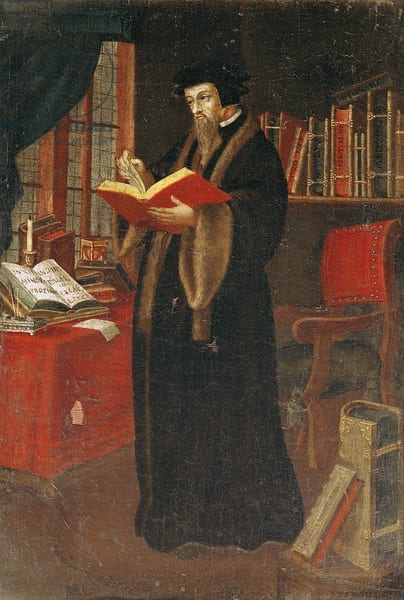

At the age of twenty-three the great French religious reformer abandoned his Catholic faith, becoming in time the founder of one of the most important branches of Protestantism. During his life he wrote numerous tracts on various aspects of religion, notably emphasizing predestination and the supremacy of the Trinity, and advocating a simpler and more austere form of Christianity.

Born Jehan Chauvin in the north of France in 1509, he was a precocious student who excelled in Latin and philosophy. Sent by his father to study the arts with the object of becoming a priest, he spent several years in a college notorious for its severe discipline, unhygienic conditions, and poor and insufficient food. According to Erasmus, he carried little away from it other than a generous supply of lice and fleas; and instead of becoming a priest he switched to studying civil law. In 1533, soon after his religious conversion, he began to advocate changes and reforms in the Catholic church.

But life in France was increasingly dangerous for “heretic” Protestants. Fearing for his life, Calvin fled his native country in 1534. He went to Basel, Ferrara, Geneva, and Strasbourg; then back to Geneva, where he remained for the rest of his life. Shy and reserved, he would have preferred to spend his life in studies but found himself propelled into religious politics. In time, with the authority of the Geneva city council, he became the religious dictator of Protestant Geneva, empowered to root out all manifestations of Catholicism and immorality.

It was an overt totalitarian regime. A kind of religion police was empowered to inspect people’s houses to ascertain they behaved according to Calvin’s ordinances. Rosaries and relics were forbidden, and it became illegal to name children after saints. “Immoral” or Catholic books were proscribed; art, music with instruments, dancing, and theater were no longer allowed. The colors of clothing, hair styles, and amounts of food permissible at the table were regulated. Gambling, drunkenness, adultery, promiscuity, immodest dress, profane songs, idolatry, heresy, and speaking ill of the clergy were punished, often by exile or execution. The press was severely censored. Education, which Calvin regarded as inseparable from religion, was carefully regulated. New schools were established, with emphasis on arithmetic, writing, and history in primary school, and Latin, Greek, and Hebrew in secondary schools to facilitate study of the Bible. Charity was placed under municipal administration to eliminate begging.

Fifty-eight people were executed during the first five years of Calvin’s rule, and seventy-six exiled. Most notorious was the case of Michael Servetus, the scientist and theologian with whom Calvin had corresponded earlier but disagreed on religious dogma. Specifically, Servetus denied the existence of the Trinity and maintained there was only one God. On his way to Italy he made the fatal error of passing through Geneva, was arrested, tried for heresy by the city council, and condemned to death. Calvin agreed with the sentence and wanted him beheaded. But the council decided to have him slowly roasted at the stake in a fire made expressly of green wood so that it would burn more slowly and prolong his agony.

From surviving documents and letters, we learn much about Calvin’s health and maladies. Because of his asceticism, it appears he was chronically malnourished, yet he survived the various epidemics that raged throughout Europe at that time, including the bubonic plague that had broken out in his city of birth in 1523. At other times he suffered from fevers, especially malaria. He was constantly overworked. During his life he wrote an enormous number of religious treatises, was always preaching, sometimes for more than an hour at a time and without notes. In Geneva he preached over two thousand sermons, once on weekdays and twice on Sundays.

For most of his life he was made miserable by hemorrhoids. They often bled, causing him to be anemic and sapping his strength. At one stage he had kidney stones and infections, discharging purulent urine and suffering from painful renal colic. He also had painful gout, and sometimes had to preach sitting down. He was always constipated, took aloes “in an immoderate degree,” and required frequent enemas. His spleen was enlarged. He had periodic facial pain, possibly trigeminal neuralgia. He suffered from heartburn and indigestion, roundworm infestation (Ascaris), migraines, nervous dyspepsia, chronic insomnia, and recurrent hemoptyses. At the age of fifty-five he died, probably from tuberculosis, although some authorities have considered subacute bacterial endocarditis.

John Calvin’s life was spent in the service of religion and his legacy is enormous, though often subject to controversy. He inspired Puritanism, Presbyterianism, and many of the reformed churches of Europe—the Netherlands, Germany—and of North America. Its various branches in their modifications exceed one-hundred million people in the world.

Further reading

John Wilkinson. The medical history of John Calvin. Proc. R. Coll, Physicians Edinb. 1992; 22:368.

Leave a Reply