Juliet McMullin

California, United States

“Arrangement in Grey and Black” is a panel from Brian Fies’ comic Mom’s Cancer (2006). Objects from Mom’s life fill this panel: a walking stick whittled on a hiking trip, her poker video game, a large Jack-in-the-Box strawberry shake, and a syringe. Moments of a life manifested on paper. Amongst the objects in this panel, the chair in which Mom is held is often an afterthought. Reclined, restful, the chair supports her as she receives the chemicals that might prolong her life.

The chemotherapy chair in comics is a mediator, an object that orients us toward specific ways of interacting. Comics are a process of visual narrative, a distillation that capture the essence of moments, circumstances, embodiment, and people, drawing lines that pull, unravel, and draw us toward the individual and contextualize relationships in the image (Chute 2015). They are a materialization of what the artist saw and a way of bringing relationships between objects into being. In comics about cancer the chair, which often disappears in textual form, is materialized. This is achieved through its relations as an orienting object; what it allows/forces people to see, and with whom they must interact (see for example Ahmed 2006). The chemotherapy chair is drawn into being, made visible through its relations to rooms, medicines, potential futures, and power relationships.

Critically, the meaning and materialization of the chair is entangled with chemotherapy. Chemotherapy as a cancer treatment is fraught with personal pain, histories of war, and hopes for a prolonged life. The chemicals in chemotherapy are simultaneously death and life, a poison that doubles as a cure (McMullin 2015). Literary descriptions such as Susan Gubar’s Enduring ovarian cancer: A memoir of a debulked woman (2012) use Kafka’s novel The Trail as a haunting parallel for chemotherapy. Gubar writes “his description of a brutal apparatus comprised of needles recurrently piercing the skin of a condemned prisoner.” Traumatic descriptions of chemotherapy focus on the relationships of toxins, needles that deploy, and bodies that receive/endure/die. Chairs that hold bodies during chemotherapy treatment are transparent in text. And yet, in drawing the moment of chemotherapy treatment, chairs are materialized in comics as part of the story. A silent partner that is necessary for orienting the narrative.

Marisa Marchetto’s Cancer Vixen (2006) is among a group of cancer comics in the mid-2000s to receive broad attention in medical, academic, and patient communities. Her story draws her eleven-month experience of being treated for breast cancer. As a cartoonist for the New Yorker, she is a keen observer able to manifest the multiple relationships with people and objects that come to define her experience with cancer. Marchetto dedicates ten pages to her first chemotherapy treatment, more than any other cancer narrative in comic form. The experience begins with her waiting to enter the treatment area. Her entrance to the treatment area is the chemo bay with several chairs. Marchetto devotes one full panel (p145), one-third of the page to the chair which she describes as a “souped up La-z-boy.” In drawing the chair and its accessories, shelves, footrest, TV, tray, she also identifies the objects that orient her toward her life outside of the chair. The tray is not just a tray but a “desk” from which she can work. On each of the ten pages, the chair orients Marchetto toward the horrors of gaining weight, her work, her battle against cancer, the toxins that threaten her hopes for a child, the chemo drip in her drawing hand, and the exhaustion of almost five hours of chemo treatment. With the description of the chemo bay and its chairs, Marchetto manifests the chair as an orienting object. As the chair slips to the background, it supports her work, conversations with doctors, her treatments, and her desires for a particular kind of future.

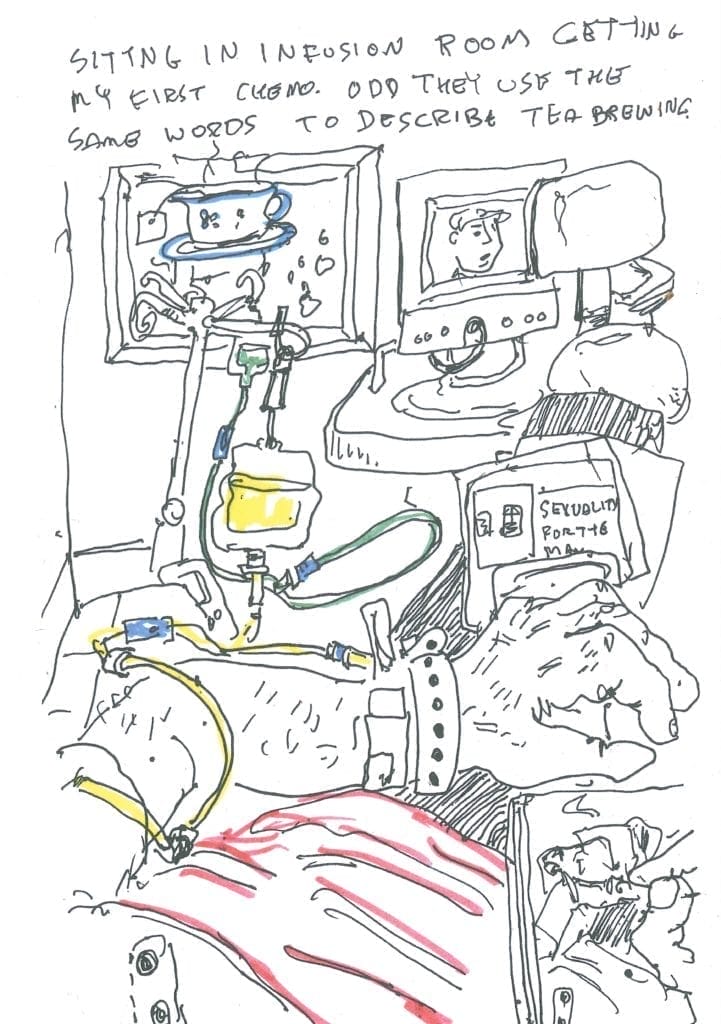

Despite the host of TVs, desks, and an assortment of gadgets to pass the time, confinement in the chemotherapy chair raises questions about objects as a relation of power. Patients are stuck as medical professionals gaze upon them, assessing the speed at which the treatment is being received, the vitals of the patient, and as a moment to “educate” the patient. In Cancer Vixen, Marchetto receives a deluge of information about side effects, dietary advice, and how to manage these concerns. In Matt Freedman’s (2014) Relatively Indolent but Relentless: A Cancer Treatment Journal, the artist’s first chemotherapy treatment is drawn. Sitting in the chair, Feedman focuses on the toxins in chemotherapy. There are IV bags, tubes connecting the chemicals to his body, TV in on in the background, magazine near him. While he ponders the similarities between brewing tea and the brewing of chemo, his arm is immobilized by the IV tubing, twisting around, taped down. The next page is a drawing of his second chemotherapy. Looking down at Matt being held by the chair, a nurse decides that she can chat with him about his prognosis. She divulges that the doctors hoped to “give him ‘two good years’” until the discovery of new treatments. Until that moment Matt had never been given a prognosis. Behind the wall of the “infusion room” he draws his tombstone with a year of death. Posed as a simple conversation, he is oriented in the chair, enduring a treatment that could prolong his life. He is also part of a relation of power, suspended for the medical gaze, to become an object of experimentation and a receptor of devastating information. At that moment he is not allowed to hope for a future but instead is forced to reassess his desires. His death is verbalized, then materialized, because he is occupying the chair.

Kaylin Andres’ (2011) Terminally Illin’ features the chemo treatment room and the chair within the first ten pages of her graphic narrative, an unusually early introduction to the chair. Her drawings of the chemotherapy chair run through the numerous orientations from Kaylin walking by the row of chairs and interacting with a young boy who is receiving his treatment. The scene uses gentle, soft neutral colors, and an exchange of pleasantries. In contrast, a dark and foreboding scene is staged for Kaylin’s chemotherapy chair. A wooden chair with spikes protruding from the sides and the footrest is a bed of nails. Similar to Gubar’s description of the torture chair, large needles with the toxins for Kaylin’s treatment aggressively point toward the seat of the chair. The back of the chair with leather straps to restrain the patient and the front of the leg rest displays a red cross, the symbol of protection and the symbol for military medical services. The word balloon with spiked edges amplifies her shock: “That’s my chemo chair?!?” Noticing Kaylin’s fear, the nurse asks if she is having a panic attack and offers a cup full of anti-anxiety and anti-depressant pills. As the pills begin to do their work, Kaylin feels the drugs rushing through her body. Determined to battle cancer, and relaxed by pills, the chair becomes an easy chemotherapy chair and Kaylin falls asleep. Sleep opens the door to an Alice in Wonderland adventure, with Kaylin shrinking into a microbial size, falling down a “rabbit hole,” and joined by her cat “Iceman.” Kaylin is transported to the inner workings of her own body so she can meet cancer face to face and “kick its ass.” Unlike the other images of the chemotherapy chair as a safe place that holds you, this chair, Kaylin’s chair, is anything but. It orients her toward an aggressive medicine that will go to any lengths to rid her body of cancer. The risks of the “war on cancer,” between the ensuing battle and promises of what sitting in a chemotherapy chair hold are vividly marked in Terminally Illin’. The chair must be there to orient people toward medicine to accommodate the medical gaze and support the chemical battle that may prolong their life.

Chemotherapy is a standard form of treatment for most cancers. Receiving treatment and “battling” cancer is expected as part of making life flourish. The procedure calls for the support of the chair, which in text is rendered invisible, and yet its relationality to toxins, cancer, patients, and medical personnel are drawn into being, made visible through comics. The consistency by which the chair is materialized in comics about cancer orients the author, patient, and reader to ordinary, standardized, normalized, objects necessary for life with cancer and to the nuances and exercise of power.

References

- Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006).

- Andres, Kaylin and Jon “Solo” Mojeske. Terminally ‘Illin. (San Francisco: Last Gasp, 2011).

- Chute, Hillary L. Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form (Cambridge: Harvard University Press 2016).

- Freedman, Matt. Relatively Indolent but Relentless: A Cancer Treatment Journal. (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2014).

- Gubar, Susan. Memoir of a Debulked Woman: Enduring Ovarian Cancer (New York: W.W. Norton & Co, Ltd, 2012).

- McMullin, Juliet. “Zombie Toxins: Abjection and Cancer’s Chemicals.” In The Walking Med: Zombies and the Medical Image, edited by Lorenzo Servitje and Sherryl Vint, 105-122. (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2016).

- Fies, Brian. Mom’s Cancer (New York: 2006)

- Marchetto, Marisa Acocella. Cancer Vixen: A True Story. New York: Pantheon Books, 2006.

JULIET MCMULLIN, PhD, is a professor of anthropology at the University of California, Riverside. As a cultural and medical anthropologist, her recent work explores how storytelling about illness in comic form creates communities of support. Her projects are committed to creating opportunities for people to share their stories. She is the author of The Healthy Ancestor: Embodied Inequalities and the Revitalization of Native Hawaiian Health, an ethnography of the relationship between land, health, and political sovereignty in Hawaii; and an edited volume Confronting Cancer: Metaphors, Advocacy, and Anthropology which examines social understandings of cancer. She also has several articles exploring graphic medicine.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

One response

Your blog beautifully illustrates the poignant journey of cancer treatment through the lens of comics, highlighting the often-overlooked chemotherapy chair as a central, supportive character. By visualizing the experience, you’ve brought empathy and understanding to a challenging aspect of medical care. Thank you for this insightful perspective.