James L. Franklin

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

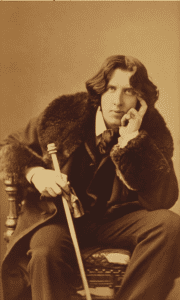

| Portrait of Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) in New York, 1882. |

Early in the afternoon of November 30, 1900, thirty-six hours after he had lapsed into a coma, a man named Sebastian Melmoth died at the Hotel d’Alsace in the Rue des Beaux Art. His assumed name eluded few as to his true identity, Oscar Wilde. The cause of his fatal illness was meningoencephalitis, a complication of a chronic middle ear infection manifested by otorrhea and unilateral deafness. That Oscar Wilde’s father, Sir William Robert Wilde (1815 – 1876), was a distinguished Irish eye surgeon and pioneer in the field of otology in the nineteenth century has been cited as the first in several ironical facts in the biographies of both men.

Following an unsuccessful libel suit brought by Oscar Wilde against the Marquess of Queensberry, Wilde was arrested on April 6, 1895 for “gross indecency” under Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment of 1885. After an initial trial in which the jury was unable to reach a verdict, Wilde was again tried and found guilty on May 25, 1895. He was sentenced to two years imprisonment and hard labor from May 25, 1895 to May 18, 1897. In July of 1896 he submitted a petition to the Home Secretary from Reading Gaol stating that he was suffering from total deafness in the right ear and an abscess that had perforated the ear drum. He stated that the symptoms had been present during the entire time of his imprisonment, and beyond irrigation with water on three occasions he had received little attention. The petition brought an outside practitioner who certified the presence of a perforated left tympanic membrane and a foul discharge.

After serving his two-year sentence, Wilde left England and resided in Dieppe on the Normandy coast, Italy, Switzerland, the Riviera, and Paris. He resumed many of the bad living habits he had acquired prior to his imprisonment; a lack of exercise, over-eating, and abuse of alcohol. In early October 1900, he was seen by Dr. Maurice a’Court Tucker, the British Embassy doctor, for headaches and a flareup of his chronic ear infection. A surgeon was called in and on October 10, 1900 an operation was performed under chloroform in Wilde’s hotel room. The surgery was major and expensive, £60, which would be about £3000 in today’s currency. A dressing attendant, daily dressing changes and open wound packings, and frequent morphine injections were required. His condition worsened during the first three weeks of November when he became delirious and unable to get out of bed. Dr. Tucker called in a Parisian physician, Dr. Paul Claisse, who had an academic background in medicine. The two physicians signed a joint statement that Mr. Oscar Wilde had serious cerebral disturbances resulting from long-standing suppuration of the right ear and made a diagnosis of “meningoencephalitis.” The absence of localizing signs made “surgical intervention” untenable. He was given the Last Rites of the Catholic Church thirty-six hours before his demise and may have been aphasic at that time.

Ashley H. Robbins and Sean L. Sellars in their contribution to “Department of Medical History” in The Lancet, believe that Wilde suffered from a cholesteatoma with secondary infection of the middle ear and mastoiditis that led to a fatal meningoencephalitis.1,i They do not believe that his terminal illness was due to syphilis as was so often claimed in the literature. Reviewing the status of mastoidectomy surgery at the time, the authors propose that the operation was a radical mastoidectomy as developed in Germany during the last quarter of the nineteenth century.2 The authors find further irony in the fact that eight weeks after Oscar Wilde died, his fourteen-year-old son Vyvyan underwent a mastoidectomy for acute mastoiditis and was left with a permanent loss of hearing in his left ear.

|

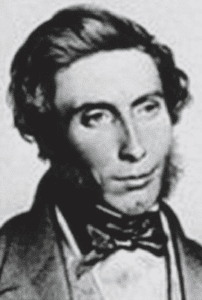

| William Robert Wills Wilde, MD. Portrait by Thomas Herbert Maguire. 1847. |

It is well worth dwelling on the life and career of Oscar Wilde’s father, Sir William Robert Wilde (1815 – 1876). William Wilde was a man of serious purpose who wore many hats. In addition to his accomplishments in the fields of ophthalmology and otology, he played a major role in the Irish Census from 1851 through 1871, developing important statistical methods for presenting and analyzing the results. He was further recognized for his contributions as a naturalist, archeologist, and Celticist.

He was born at Kilkeevin in County Roscommon, Ireland, the son of a prominent local practitioner, Thomas Wills Wilde. His interest in Irish antiquities and folklore began as a youth when he accompanied his father on his rounds in rural Connaught. His medical education included apprenticeships with prominent Dublin surgeons Abraham Colles, James Cusack, and Sir Philip Crampton. In 1837 he earned his medical degree from the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland.

Through two of his Dublin mentors, the physicians Robert James Graves and William Stokes, Wilde obtained a position on a private yacht, Crusader, as the medical attendant to a wealthy invalid.ii The eight-month voyage took him to the Holy Land and throughout the Mediterranean. J. McGeache has drawn an interesting parallel to the almost simultaneous career of Charles Darwin aboard the H.M.S. Beagle.3 In 1840 on his return to Dublin, Wilde published Narrative of a Voyage to Madeira, Tenerife and Along the Shores of the Mediterranean, a two-volume account of natural history, climate, and medical aspects of the ports visited aboard the Crusader. The work also included his thoughts on the subject of Celtic origins. It became an instant best seller and led to his membership in the Royal Irish Academy, the Royal Dublin Society, the Royal Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons, and Trinity College. While in Egypt he observed specialist facilities for the treatment of infectious ophthalmic trachoma, which had spread to Europe and Ireland after the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt. Income from this publication allowed him to travel to Vienna and observe the scientific advances being made in the field of otology. In 1843 he published Austria: its Literary, Scientific, and Medical Institutions.

In 1841, Wilde was appointed as assistant commissioner of the Irish Census. Through this position he was able to gather important information on the status of both the blind and deaf in Ireland in addition to applying the most comprehensive analyses of medical data in the nineteenth century.4 For his work on the Irish Census in 1851 and 1861, he was knighted in a ceremony at Dublin Castle in 1864.

In 1845 he became the editor of the Dublin Journal of Medical Science. He established a successful specialty practice and founded St. Mark’s Hospital for Diseases of the Eye and Ear in Dublin. He was appointed Surgeon Oculist in Ordinary to the Queen in Ireland in 1853. Wilde authored a scientifically modern textbook in 1853, Practical Observations on Aural Surgery and the Nature and Treatment of Diseases of the Ear. He is credited with making an important contribution to mastoid surgery, the post auricular incision or Wilde’s incision, as well as a dressing forceps and an aural snare.5

|

|

Jane Francesca Agnes, Lady Wilde (born Jane Francesca Elgee in Wexford) was an Irish poet under the pen name “Speranza.” |

Before Wilde married in 1851, he had fathered three illegitimate children. The first, a son Henry Wilson (1838 – 1877), whom he completely acknowledged, became a doctor and worked closely with his father writing the first book in English on ophthalmoscopy.iii William Wilde’s wife, Jane Francesca Agnes Elgee, was a poet and Irish Nationalist. Writing for the Young Ireland movement of the 1840s she published pro-Irish, anti-British editorials under the pen name of Speranza in the Irish journal the Nation. As a result, the Dublin authorities shut down the journal and charged its editor, Charles Gavan Duffy, with sedition. Duffy was acquitted when he refused to divulge the identity of their author, asserting his need to protect a lady of respectability. The couple had two sons, Oscar and his older brother William, and a daughter, Isola Francesca, who died in childhood. Notorious libel suits would play an ironic role in the lives of Sir William Wilde and Lady Wilde, as well as their son, Oscar.

In July 1854, a nineteen-year-old woman named Mary Treavers and her mother visited William Wilde’s surgery with problems related to her hearing. Her father, Dr. Robert Treavers, was a professor of medical jurisprudence at Trinity College in Dublin. With the permission of her father, Dr. Wilde undertook her informal education and gave her work correcting manuscripts. At first she became part of the family, but then a falling out with Jane Wilde altered their relationship. Jane Wilde returned a photograph of herself that Mary had sent to Doctor Wilde. It is possible that Sir William Wilde may have tired of her, and he tried to send her on to Australia where her brothers had settled. The Wildes provided money for her transportation, and on two occasions she started on her journey only to demure after booking passage from Liverpool. Her behavior became further unhinged and she took an overdose of laudanum for which Wilde had to assure that she took an antidote. She also went as far as sending the Wildes a fake death notice.

Mary then wrote a pamphlet, Florence Boyle Price or a Warning, using Jane’s pen name, Speranza. It was a story of Dr. and Mrs. Quilp, containing an episode that reads like an attempted rape by Dr. Quilp under chloroform anesthesia. In 1863 Mary Treavers had one thousand copies printed and sent them to William Wilde’s patients. In April Sir William was to give a lecture at Metropolitan Hall in Dublin, “Ireland, Past and Present: The Land and the People.” Mary hired five newsboys to hold placards in front of the lecture hall reading “Sir William Wilde and Speranza” and advertising the pamphlet. They also distributed fliers with extracts of Sir William’s letters to Mary Treavers suggesting a relationship beyond that of doctor and patient. She further pursued the Wildes when they left Dublin to stay in Bray by having copies of the pamphlets delivered to their neighbors.

Jane wrote Mary’s father protesting the activities of his daughter and her insinuation that there had been an “intrigue” between Miss Treavers and Sir William Wilde. Mary sued Lady Jane for libel over the contents of the letter, demanded £2000 in damages, and named Sir William as a codefendant. The Wildes refused to settle and the case went to court on December 12, 1864 with a previously good friend, Isaac Butt, representing Mary Treavers in court.

In addition to correspondence between Mary Treavers and Wilde deemed inappropriate for him to have written to the young woman, the most damaging allegation was that Doctor Wilde had taken advantage of her sexually while rendered unconscious by chloroform administered while treating her for a burn mark on her neck in his surgery.

|

| Oscar Wilde (with white tie) and his brother, Willie, caricature by Sir Max Beerbohm (Humanities Research Center, University of Texas, Austin). |

Lady Wilde on the witness stand displayed a certain arrogance toward the proceedings. Sir William did not take the witness stand to deny the charges against him, and Isaac Butt used this against Dr. Wilde, accusing him of hiding behind his wife. The judge dismissed the rape charge because it had not been reported at the time and because Mary Treavers continued to correspond with Doctor Wilde. The jury ruled that Mary Treavers had been libeled by the letter to her father, but she was awarded a farthing and the Wildes were responsible for the court costs of £2000 (equivalent to £250,000 in today’s money).

In Mad, Bad, Dangerous to Know, the novelist Colm Tóibín observes a number of remarkable similarities in the case of Mary Treavers versus Lady Wilde and the libel suit that Oscar Wilde filed against the Marquess of Queensberry.6 Mary Treavers and the Marquess of Queensberry sought to publicly embarrass Sir William Wilde and Oscar Wilde, respectively. Mary had done so with her pamphlet and activities during Sir William’s lecture in Dublin. The Marquess of Queensberry attempted to publicly disrupt the opening night performance of The Importance of Being Earnest in 1895. To this end they also both left printed accusations: Mary Treavers’ pamphlet Florence Boyle Price or a Warning, and Queensberry’s card, “posing as a sodomite,” left at Oscar Wilde’s London Club. Both parties claimed corruption by one of the Wildes, Mary Treavers by Sir William Wilde, and Queensberry’s son, Lord Alfred Douglas, by Oscar Wilde. The content of works of fiction was brought into evidence in each trial against the witnesses: Jane Wilde’s translation of a scandalous novel and the contents of Oscar Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray. Both Lady Wilde and Oscar Wilde made light of the proceedings while in the in the witness box. In both cases, the lawyers for the other side were well known to the Wilde family: Isaac Butt in the case against the elder Wildes, and Edward Carson, who represented the Marquess of Queensbury, against Oscar Wilde. Carson and Wilde had both been at Trinity College together and as Oscar Wilde observed when he learned that Carson would take the case against him: “No doubt he will perform his task with the bitterness of an old friend.” The trial brought Isaac Butt much business in his legal practice; both he and Carson were ambitious men who went on to become prominent politicians.

While Oscar Wilde was sentenced to hard labor in prison for two years, the social status of the Wildes and Dr. Wilde’s practice did not suffer. Sir William was praised in an editorial by The Lancet. The London Times was less sympathetic to Wilde’s conduct with regard to young Mary Treavers.

For Oscar Wilde, his trial and the two years he spent in prison had a profound effect on his life. The nature of his confinement in prison was quite harsh. In addition to manual labor, he was denied contact with news of the outside world and the diet and isolation took their toll. “The numbing shock of his abrupt translation from a pampered self-indulgent socialite led as might be expected to sleeplessness, depression, dyspepsia, anorexia and weight loss.”7 The prison warden and physician were hostile and without sympathy. On one occasion when he felt unwell, he was forced to attend chapel, sustaining a fall and seriously injuring his ear. He petitioned against the care he was receiving and was transferred to the Infirmary and subsequently Reading Gaol, where the conditions of his confinement relaxed. Paradoxically, the improved diet and abstinence from alcohol was such that when he was released from prison, his physical health was better than it had been for years.

On being released from prison on May 19, 1897, he immediately left England, never to return. His trial and legal troubles exacted a severe burden for his wife and children. His wife Constance moved away from London and changed the family name to “Holland.” Legal costs incurred by the trial forced them into bankruptcy, and she would further suffer from a progressive spinal paralysis suspected to be a manifestation of tertiary syphilis contracted from her husband at the time of her marriage.7 There is evidence that Wilde acquired syphilis while an undergraduate at Oxford from a well-known local prostitute. He may also have received mercury injections as treatment for the disease, which resulted in the black and carious state of his teeth. By early 1900 while in Europe, he suffered from a chronic dermatitis which he described as being like “leopard spots” and which he attributed to mussel poisoning. The cause of the rash cannot be known but it may also have been a manifestation of a tertiary syphilitic infection.

While on the continent Wilde resumed his heavy alcohol consumption and also took to consuming absinthe. He gained excessive weight and his features became markedly bloated. The landlady of the Hotel d’Alsace reported that he was consuming a liter of brandy each day at the time of his death. His literary output withered and was confined to De Profundis, a fifty-five-thousand-word letter addressed to Lord Alfred (“Bosie”) Douglas, and The Ballad of Reading Gaol.

End Notes

- Cholesteatoma is a form of chronic otitis media in which keratinizing squamous epithelium grows from the auditory canal into the mucosa of the middle ear triggering an inflammatory reaction that can destroy the ossicles. They can become infected and result in chronically draining ears.

- Robert James Graves (1796-1853), Irish surgeon after whom Graves’ disease takes its name. William Stokes (1804-1878), an Irish physician whose name is applied to Cheyne-Stokes breathing and Stokes-Adams syndrome.

- Wilde provided for the education of his three illegitimate children. In addition to Henry Wilson, Emily and Mary Wilde were born in 1847 and 1849 respectively and were of different parentage than Henry, they were reared by his eldest brother Ralph, a clergyman. They tragically died in 1871 in a freakish accident when their dresses caught fire at a Halloween party.

References

- Ashley H. Robbins, Sean L. Sellars, Oscar Wilde’s terminal illness: reappraisal after a century, The Lancet 356: 1841-1843, November 25, 2000.

- Sellars, S.L. The Origins of Mastoid Surgery, S Afr. Med. J. 48:234-242, 1974

- J. McGeachie, Wilde’s worlds: Sir William Wilde in Victorian Ireland, Ir. J. Med. Sci, 185:303-307, 2016

- P. Froggart, The demographic work of Sir William Wide, Ir. J. Med. Sci, 185:293-295, 2016

- M. Walsh, William Wilde: his contribution to otology, Ir. J. Med. Sci. 185:291-292, 2016

- Colm Tobin, Mad, Bad, Dangerous to Know: The Fathers of Wilde, Yeats and Joyce, Scribner, NYC, 2018

- Deborah Hayden, Pox: Genius, Madness, and the Mysteries of Syphilis, Basic Books, 2004, pp. 200-228

JAMES L. FRANKLIN is a gastroenterologist and associate professor emeritus at Rush University Medical Center. He also serves on the editorial board of Hektoen International and as the president of Hektoen’s Society of Medical History & Humanities.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 2– Spring 2019

Spring 2019 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply