JMS Pearce

Hull, England, UK

Some of the earliest ideas about health and disease lie in Greek mythology. The Greeks of prehistory told, retold, and often remoulded their tales of immortal gods and goddesses that were imaginative, symbolic creations.

Stories of the gods probably started with Minoan and Mycenaean writers of the eighteenth century BC. These stories were spread by word of mouth since there were no written texts. A major advance came in the eighth century BC, when myths were chronicled in the magical writings and epic poetry of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey.1,2 These, along with the Theogony of Hesiod (c. 700 BC) and the fifth-century BC plays of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides are the most important source of the myths and fables of the gods.3

Our image of the gods owes more to romantic literature than to their everyday interactions with the Greek people. With raw, imaginative creativity they invented gods who influenced their health, beliefs, and lives. Their myths varied greatly and spread throughout civilizations, East and West. In time myths became cults cryptically embedded in religious creeds. We discover them in the stories of their gods—a word used here to include both gods and goddesses—mingled with their many “minor deities,” muses, and the nymphs of the sea, mountains, groves, and rivers.i,4

The gods were immortal, but were given human form and personalities: kind, cruel, good, or evil. They married, had children, and fought their own internecine battles. They intervened in human affairs and demanded sacrifices, prayers, and rituals. Icons, symbols, curiosities of dress, paintings, and sculptures celebrated the gods in material form.

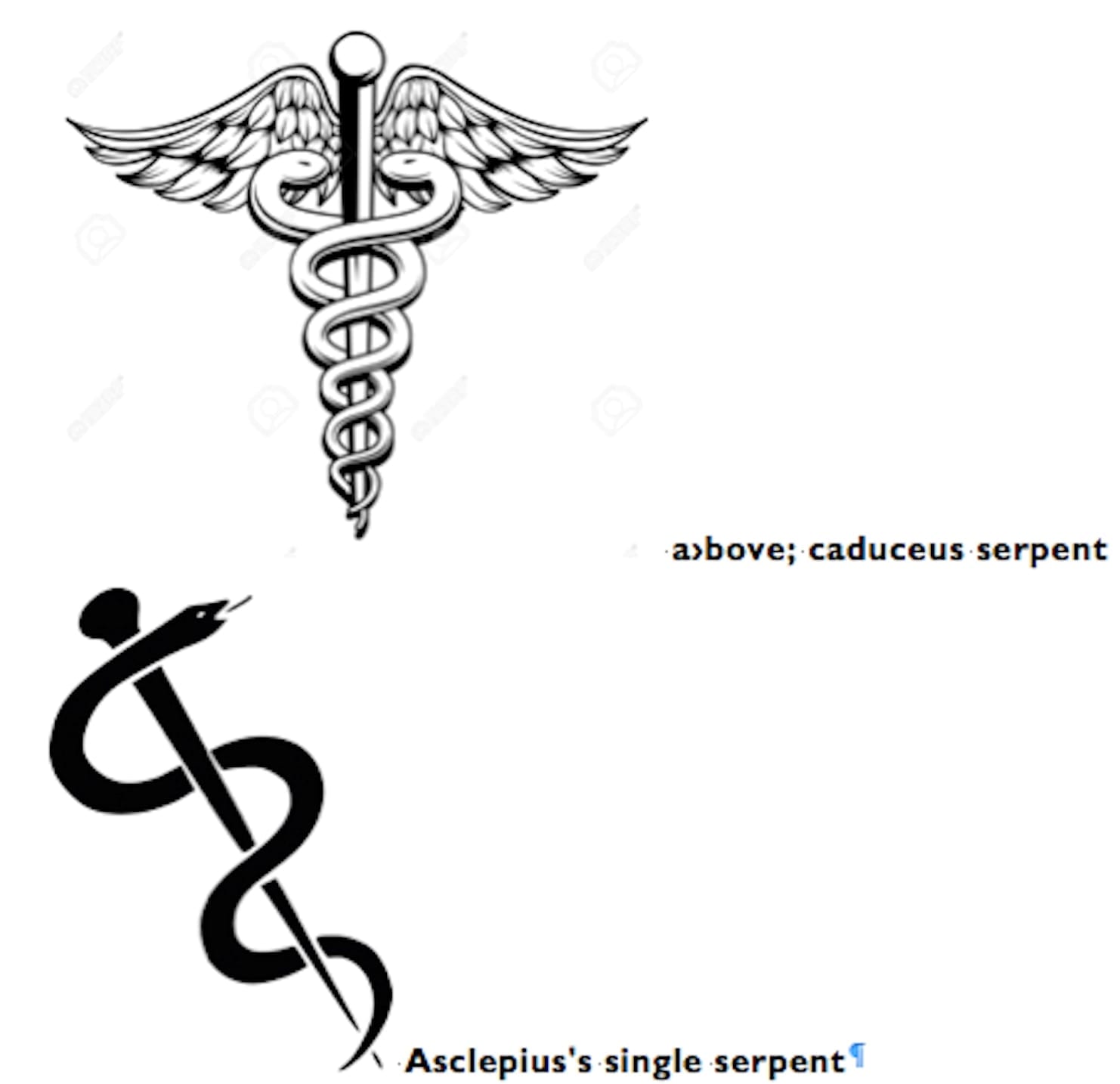

Typical of their many icons is the single serpent—totem of Medicine—the Aesculapian wand, seen in the constellation Ophiochus (the serpent holder). Serpents in ancient cultures represented fertility, associated with rebirth and strength.5 The Aesculapian wand is not to be confused with the two serpents comprising the caduceus of Hermes, or the Herald’s wand, (Fig 1.) a symbol of the Mesopotamian god of fertility. Historically it symbolized messengers, thieves, and merchants; Hermes was their patron. He was neither healer nor guardian of physicians. Seventh-century alchemists adopted Hermes’s two entwined serpents under a pair of wings as their icon, often endowed by magic. This caduceus was commonly but erroneously used as the symbol of Medicine.6

Asclepius: The birth of Medicine in Mythology

Apollo (Greek, Απολλων) was not only revered as god of Medicine but also god of the sun, prophesy, harmony, music, and art. Although associated with healing, like his twin sister Artemis, he could also inflict disease and plague. Apollo was the son of Zeus (named Jupiter by the Romans) and the Titan Leto, born on the sacred, alluring island of Delos, now site of monumental antiquities from the Classical and Hellenistic eras.

It was Apollo who snatched Asclepius (Greek, Ασκληπιος; Latin Aesculapius) from the womb of Coronis, his dying mistress. When Coronis was pregnant with Asclepius, Apollo ordered a white raven to guard her. But in his absence she had intercourse with Ischys before her child was born. The white raven told Apollo of the incident. Infuriated, Apollo placed a curse on the bird that burnt its feathers; that is why to this day ravens and other corvids are black. Apollo then instructed his sister Artemis to kill Coronis. But when he beheld Coronis’s body burning on the funeral pyre, consumed by remorse, he cut open her womb and saved the unharmed baby Asclepius. For Coronis there was no reprieve. (An alternative account in Pseudo-Apollodorus Bibliotheca states that Leukippos’ daughter Arsinoe gave birth to Asclepius.)

Apollo sent Asclepius (Fig 2.) to be taught by the centaur Chiron (hence chirugeon—surgeon, handman) renowned for his powers of healing.7,8 The pupil Asclepius’s medical skills were outstanding and soon surpassed his master’s.9,10 In the fifth century BC Pindar’s Pythian Ode describes him as:

to each for every various ill he made the remedy, and gave deliverance from pain, some with gentle songs of incantation; others he cured with soothing draughts of medicines, or wrapped their limbs around with doctored salves, and some he made whole with the surgeon’s knife.11

In Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey (iv. 232) Asclepius, at first a mortal, was raised to the status of a demi-god. He was worshipped in Greek temples dedicated to him in Trikala, Epidaurus, and Kos. In 293 BC his cult spread to Rome, where he was revered as “Aesculapius.” Homer’s Iliad portrays him as a skilful physician and the father of two Trojan healers, Machaon and Podalirius. Yet Plato’s Dialogues relate his opposition to treating those disabled by illness: “valetudinarian arts,” and “he saw no good in a life spent in nursing disease to the neglect of customary employment”—an ethical controversy, with us today.11

So great was his ability in Medicine that with the blood of the Gorgon—a gift from the goddess Athena—he restored life to the dead. This proved to be his downfall when it goaded Hades, god of the Underworld, to resentful retribution because he thought that dead souls rightfully belonged to his realm. Despite Apollo’s pleas to save his son, Hades persuaded the mighty Zeus to kill Asclepius with a thunderbolt to preserve his monopoly over life and death.

After death Asclepius was placed among stars as the constellation Ophiochus. The plant genus named Asclepias, or milkweed, contains cardiac glycosides, which remind us of Asclepius’s healing powers. Many temples (asclepeions) were built in his honor where hosts of pilgrims sought miraculous healing. Near Kos is the Asklepieion, ruins of an ancient hospital built in 357 BC after the death of Hippocrates (c. 460-c. 375 BC), dedicated to Asclepius. The terraced sanctuary was home to the Asklepiadai, a priestly order of healers. In the Protagoras, Plato called Hippocrates “the Asclepiad of Kos.”

Asclepius’s healing powers were continued by his son Telesphoros, the god who brought recuperation from illness and the wounds of war. He was depicted on ancient statuettes and reliefs as a boy wearing a cloak and hood or Phrygian cap, holding a scroll or tablet.ii Asclepius with Epione (Greek: soothing) also produced a dynasty of five daughters: Hygeia, Panacea, Akeso, Iaso, and Aegle, and three medical sons: Telesphoros, Machaon, and Podalirius. Hygeia’s famed cult of cleanliness and good health, later named hygiene, began around the seventh century BC, influenced by Athena, goddess of wisdom and war, worshipped at the Delphic Oracle on Mount Parnassus.

Gods and goddesses of healing

There were countless Greek gods and goddesses of healing and health.13 They represented natural phenomena, and appear in Roman and many other religious traditions including Hinduism, Buddhism, Paganism, and in the ancient cultures of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, and Africa. Each goddess had her unique powers, symbols, and rituals. In Greek myths we find the daughters of Epione and Asclepius, following the healing heritage:

- Akeso, the goddess responsible for healing wounds and curing illnesses.

- Aegle, goddess of radiant good health. She was an attendant of her father.

- Hygeia, (Fig 2.) goddess of cleanliness and good health and companion of Aphrodite. She was summoned with Asclepius to Athens c. 430 BC to deal with the epidemic plague.

- Iaso, goddess of recuperation from illness, and healing remedies that complimented her sister Hygeia’s preventive practices.

- Panakeia (Panacea), goddess of universal remedies or healing, often by using potions.

- Paeon was a deity, physician of the Olympian gods, mentioned by Homer. He healed the wounds of wars inflicted by other gods. “Paean” also became a common epithet for Apollo and then for Asclepius.

Conclusion

Before Hippocrates the beginnings of Greek Medicine are mostly blank pages.14 Scholars view the texts based on Egyptian and Babylonian traditions within the complex of culture and natural philosophy, religion, and mysticism.15 But Greek myths did not provide divine revelations or spiritual teachings. The Greeks believed in an estimated 350 or more anthropomorphic gods and goddesses under one supreme god, Zeus, and his austere wife, Hera, goddess of women, who controlled their lives and fortunes. In Homeric verses twelve “major gods” dwelt on Mount Olympus after they had defeated the legendary Titans.iii The Greek people (demos) did not revere gods as idols of perfection, but recounted their jealousies, their bruising irons of wrath as ministers of chastisement, their irregular sexual practices, as well as their wisdom, kindness, medical skills, miraculous acts, and transformations. In the sixth century BC, the Ionian philosophers challenged but failed to erase these traditional beliefs. At the beginning of the fifth century BC, the philosophers Heraclitus and Xenophanes scorned both the cults and gods, as did the later Sophist philosophers. However, the Romans adopted many such concepts; and several medical words in current use have their roots in the persisting influence of Greek myths and gods, for example: Atlas, Achilles, Artemisinin, Iris, Hypnos, and his son Morphine.

Many modern ideas of tending the ill and injured, using herbal, dietary, and surgical remedies hark back to these myths. The Hippocratic corpus was influenced by Asclepius but founded practices based on observation and reason. The lasting principles of the Hippocratic oath recalling the Asclepian dynasty remain the earliest statement of medical ethics:

I swear, calling upon Apollo the physician and Asclepius, Hygeia and Panaceia and all the gods and goddesses as witnesses, that I will fulfill this oath and this contract according to my ability and judgment . . .

The healing figures of the Greek myths, legends, and captivating stories bear both archaism and a literally fabulous, mythical quality that lends to these tales something of the universal truths and hopes to which all great literature aspires.

End notes

- i. The Oceanids were sea nymphs; the Nereids inhabited both salt and freshwater; the Naiads nymphs of springs, rivers, and lakes. The Oreads were nymphs of mountains and grottoes; the Napaeae (and the Alseids) were nymphs of glens and groves; the Dryads were nymphs of woods and trees.

- ii. Many of disputed authenticity, e.g. the two small bronze figures labelled Telesphoros in the British Museum, and the marble statuette in the Louvre called Telesphoros by Clarac.

- iii. Zeus (Jupiter), Hera (Juno), Hephaestus (Vulcan), Athena (Minerva), Hermes (Mercury), Artemis (Diana), Apollo (Apollo), Dionysus (Bacchus), Ares (Mars), Aphrodite (Venus), Demeter (Ceres), and Poseidon (Neptune). Roman names in parentheses.

References

- Homer. The Iliad. Translated Martin Hammond. Penguin Classics 1987.

- Homer The Odyssey (Penguin Classics): Rev Ed edition. 2003

- Caldwell R. Hesiod’s Theogony, Focus Publishing/R. Pullins Company. 1987.

- Fry S. Mythos: The Greek Myths Retold. Michael Joseph. 2017.

- Dunea G. Caduceus versus the Staff of Asclepius. Hektoen Int. Volume 9, Issue 4 – Fall 2017

- Pearce JMS. The Caduceus and the Aesculapian Staff. Quarterly Journal of Medicine 1995;88:678-9.

- Walton A. The Cult of Asclepius. Boston. Ginn & Company, 1894.

- Oliver JR. Greek Medicine and Greek Civilization Bull Inst Med Hist, Baltimore 1935; 3: 623-6. et seq.

- Edelstein E J, Edelstein, L. Asclepius: Collection and Interpretation of the Testimonies Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1998.

- Theoi Greek Mythology. Aaron J. Atsma, ASKLEPIOS.

https://www.theoi.com/Ouranios/Asklepios.html - Myers E. The Extant Odes Of Pindar. Translated into English. London: Macmillan and Co. 1874.

- The dialogues of Plato. Benjamin Jowett.1817-1893; Royal College of Physicians of London. Oxford: Clarendon Press 1892; iii. 95..

- Pollard JRT, Adkins AWH. Greek mythology. Encyclopædia Britannica 2018. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Greek-mythology

- Majno G. The healing hand: Man and wound in the ancient world. Cambridge Massachusetts.1975.

- Liebson PR. Philosophy of science and medicine series III: Greek science. Hektoen Int. Hektorama:Science. Summer 2016.

JMS PEARCE MD, FRCP, is emeritus consultant neurologist in the Department of Neurology at the Hull Royal Infirmary, England.

Leave a Reply