Piper Haitsuka

Kailua-Kona, Hawaii, USA

|

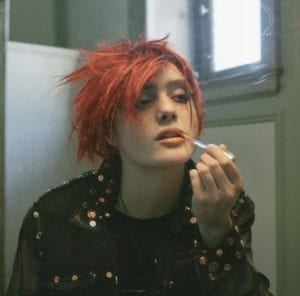

| Transgender role model, Casil Mcarthur |

Identity characterizes who a person is. Physical, mental, or chemical identity can have an array of diverse meanings. Gender and sex are two very different concepts that influence identity, but are often confused as being interchangeable words.1 Sex is a biological classification, whereas gender is a social science concept with a “range of physical, mental, and behavioral characteristics distinguishing between masculinity and femininity.”2 Gender identity is a representation of “one’s personal experience of one’s own gender.”3 Individuals themselves determine their own unique gender identity.

Sex is not always simple to distinguish either. “Intersex” describes people who are physically between sexes due to conditions that include chromosomal and hormonal variations. People who are intersex may have greater challenges with gender identity. Parents of intersex children are faced with a decision of whether to pursue surgical or hormonal interventions, a topic which remains controversial.4

A person who is cisgender “has a gender identity consistent with the sex they were assigned at birth.”5 Someone who is transgender has a gender identity different from the sex they were assigned. People who are transgender may choose to have surgical or hormonal procedures to address dysmorphia, a perceived flaw in appearance. Pathak and Pathak write, “Categorizing males and females into social roles creates a problem, because individuals feel they have to be at one end of a linear spectrum and must identify themselves as man or woman, rather than being allowed to choose a section between.”6

If a person does not identify with a specific gender, terms like non-binary, agender, and genderqueer may be applied. In some cultures, “third gender” is used to categorize people who choose not to be labeled as male or female; they are referred to as a completely different gender, where “third” can mean “other.” These people may live in places and cultures where the views of the modern world have not been present to influence views on gender, which provides greater freedom for the exploration of gender identity.7

Since it is not possible to know a person’s gender by looks alone, it is appropriate to ask for pronouns before making assumptions. These pronouns should align with the person’s gender identity. Pronouns such as “they” and “ze” are acceptable to use when someone prefers not to define as feminine or masculine and “avoid specifying the gender of the person.”8

In the 1970s, feminist theory embraced the concept of a distinction between biological sex and the social construct of gender.9 Social expectations attempt to interpret biological differences between men and women to determine “access to rights, resources, power in society, and health behaviors.”10 These constructs “tend to typically favor men, creating an imbalance in power and gender inequalities within most societies.”11 Because feminism seeks to establish “equality of the sexes,”12 not exclusively support rights of women, feminism also advocates for change in issues of gender inequality and traditional gender roles. The goal is to have equal opportunities for people of every sex, gender, race, sexuality, and situation.

Millennial individuals are beginning to see “gender as a spectrum” instead of “as a binary.” This means that people are identifying as in-between genders, both genders, or denying having a gender at all. As gender is increasingly recognized as something that may be fluid rather than permanent, societies must adopt and promote measures of equality and civil rights that allow all humans to identify and live as they choose to.

References

- “What do we mean by ‘sex’ and ‘gender’?” (Nov. 26, 2015). World Health Organization. Accessed Mar 17, 2018.

- Udry, J. Richard (Nov 1994). “The Nature of Gender.” Demography. Accessed Mar 17, 2018.

- Morrow, Deana F. and Messinger, Lori (2006). “Sexual Orientation and Gender Expression in Social Work Practice” (8). Accessed Mar 17, 2018.

- Macur, Juliet (Oct 6, 2014). “Fighting for the Body She Was Born With.” The New York Times. Accessed Mar 17, 2018.

- “Understanding Gender.” Gender Spectrum, 2017. Accessed Mar 18, 2018.

- Pathak, Sunita, and Pathak, Surendra. “Gender and the MDGs with Reference to Women as Human.” Academia.edu. Accessed Mar 17, 2018.

- Roscoe, Will (2000). “Changing Ones: Third and Fourth Genders in Native North America.” Palgrave Macmillan (Jun 17, 2000). Accessed Mar 2018.

- “They.” Online Etymology Dictionary. Accessed Mar 18, 2018.

- “GENDER.” Social Science Dictionary. Accessed Mar 17, 2018.

- Galdas, P.M.; Johnson, J. L.; Percy, M. E.; Ratner, P. A. (2010). “Help Seeking for Cardiac Symptoms: Beyond the Masculine-Feminine Binary.” Social Science & Medicine. Accessed Mar 17, 2018.

- Warnecke, T. (2013). “Entrepreneurship and Gender: An Institutional Perspective.” Journal of Economic Issues. Accessed Mar 17, 2018.

- Beasley, Chris (1999). What is Feminism?. New York: Sage. pp. 3-11. Accessed Mar 18, 2018.

PIPER HAITSUKA, lives in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii and is currently a senior at Makua Lani Christian Academy. She reads a multitude of books each year, as well as a plethora of poems and short stories. Writing gives her a voice of expression which she hopes to use for work in journalism and advocacy.

Leave a Reply