Timo Hannu

Helsinki, Finland

|

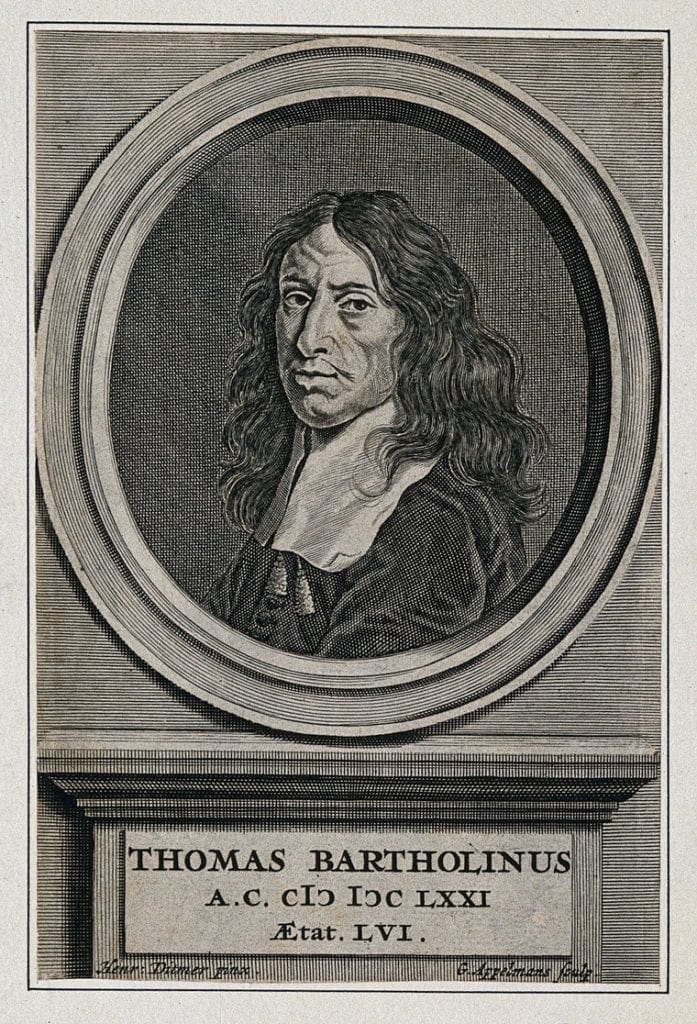

| ‘Thomas Bartholin. Line engraving by G. Appelmans, 1671, after H. Ditmer.’ by Heinrich Ditmer. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY |

Thomas Bartholin (1616-1680) was a Danish physician known for his discoveries on aspects of the human lymphatic system. Like his father, Caspar Bartholin the Elder, he was a professor of medicine, and so would be one of his sons, Caspar Bartholin the Younger, who described Bartholin’s duct and Bartholin’s glands.

Thomas Bartholin was a prolific writer who wrote on subjects of medicine and also theology. In 1670, a fire broke out on his estate, located some distance from Copenhagen, and destroyed his personal library including unpublished manuscripts. Based on this misfortune, Bartholin wrote for his consolation in 1670 a treatise, De bibliothecae incendio dissertatio ad filios, which starts as follows:

“For it was while I was paying full respect to my deceased teacher, the revered Moth, that I was interrupted by the dire message that my dwelling at Hagestedgaard had been destroyed by fire, and together with the rest of the household goods the library, a collection of the most esteemed physicians and philologians who had lived in repose with me and daily consumed my leisure.”

Bartholin was not alone in his destiny. In his treatise, he summarized famous fires in which books and libraries had been vanished by Vulcan, the god of fire. According to Bartholin, there was no kingdom nor court that Vulcan had not been willing to ruin. Here he mentioned the Sybilline books, the sacred books of Jerusalem, and the Alexandrian library, among others.

Bartholin bore the calamity more bravely because “it has long been customary for Vulcan to rage in our family. Those very famous medical and mathematical books of my revered grandfather, Master Thomas Finck, were consumed by fire, a loss which the venerable old man never recalled without tears although he was otherwise unaffected by emotions.”

Bartholin viewed the fire as a punishment or test from God. To cope with his loss he mixed Christian values with the wisdom of stoicism: “Vulcan has exercised control over my goods, not my spirit, and he has raged among innocent papers so that he might instruct me in steadfastness,” and “I saw no good reason to depart from my accustomed tranquility of spirit since my wife was unharmed, my children survived and I myself was unharmed.”

Bartholin added that: “nor must fire always be considered as a sign of God’s punishment, although none of us lacks sin.” The kindness of flames had been shown by God “when Moses, Elijah, and Solomon performed sacrifices, fire was sent from the sky and burned and consumed the victims.”

Bartholin found solace in knowing that “either I am able to buy them [books] again for money, or because they have already been sufficiently read and I can do without them in my old age.” Bartholin thought that God ordered him to consider another way of living: “I concern myself wholly with the immortal concerns of God and spirit,” and “I shall devote myself to those more valuable matters concerned with meditation upon death so that I may depart from life better and more felicitous.”

At the end of his consolation, Bartholin catalogued the manuscripts and books lost in the fire. The first list comprised twenty-seven works which he had prepared to be published. “Here the reader will see what he may desire in the future but will never read.” The second list was “a catalogue of my personal library constructed from works hitherto published in my name or dedicated to me, which Vulcan consumed with the rest, but with less harm to me since they are available elsewhere.” The latter catalog had 129 items, including revised editions and translations of Anatomia, which his father had first published in 1611 as Anatomicae Institutiones Corporis Humani, and had served as a standard medical textbook of anatomy for decades.

References

- Bartholin T. On The Burning of His Library and On Medical Travel. Translated by Charles D. O’Malley. The University of Kansas Press, Lawrence, 1961.

TIMO HANNU is a specialist in occupational health and in occupational medicine. He has published scientific papers on rheumatology, infectious diseases, and occupational medicine. He is currently working as a medical expert in the Social Insurance Institution of Finland in Helsinki. He is interested in the history of medicine and medical humanities.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 2– Spring 2019

Fall 2018 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply