Joseph deBettencourt

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

|

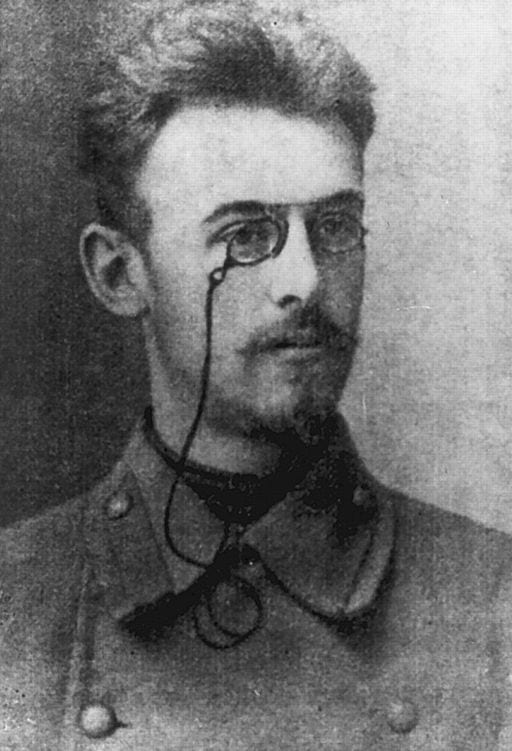

| A portrait of Nikolai Sergeevich Korotkov |

I’m watching, knees bending,

Looking meek, my heart quiet,

Drifting away are the shadows

Of fussy world affairs

While I’m envisioning, dreaming of

voices from other worlds

-Aleksandr Blok, untitled poem, July 3, 1901a

Stepping off the train in northern China, Nikolai Korotkov was the farthest he had ever been from home. He would have heard the sounds of men laying railroad ties and hastily assembling accommodations for the newly arrived Russian troops. After graduating with honors from the Imperial Moscow University, the bright young doctor had been sent by his school to assist the Russian Red Cross in Jilin and Liaodong provinces during the Boxer Rebellion.2 Though he may not have known it at the time, the sound of skirmishes in the distance and the bustle of the military hospital would become the constant soundtrack of his career. Not much is written about his first trip to China, the rebellion lasting roughly one year, after which he returned to Saint Petersburg to teach at a Military Academy. However, this assignment to the Boxer Rebellion would set the stage for many of Korotkov’s most famous discoveries as well as for the future of Russia.

Russia had used the Boxer Rebellion to reinforce their hold on the north east of China; their troops had moved in initially to protect and support the Chinese government but then never left.3 The Russian government took control over Port Arthur, a naval base in Liaodong province. While this was concerning for China, it was also alarming to nearby Japan. The Japanese, currently at war with China, felt this move threatened their military control of the region and animosity began building. Korotkov, having spent time in Liaodong and now working at a military academy, would likely have been aware of the tension brewing in the East. In 1904 Port Arthur was attacked by the Japanese and war was declared, beginning the Russo-Japanese War. Korotkov boarded a familiar train and headed back towards the conflict. Having worked as a physician during the Boxer Rebellion, it is possible he believed the experience would be similar. When he arrived in the city of Harbin, however, he was greeted with a much different kind of war. The Boxers had proven little match for the massive Russian army, but in this current war with Japan, the Russian military was facing a harsh reality.4 They sustained heavy casualties throughout the war, and those wounded men were brought back to be treated in Korotkov’s hospital. As they worked to save men’s lives, Korotkov and his fellow surgeons faced a struggle familiar to many wartime doctors at the time. While they could often locate lacerated vessels and ligate them, preventing massive blood loss, the limbs would never recover and eventually be lost to gangrene. Surgeons of the day had no idea if a limb would survive after an emergency ligation of vessels; what they wanted was a way to better predict the outcome of their efforts.2

|

|

| Soldiers marching, 1st Russian army, Russo-Japanese War |

By 1896 an inflatable elastic cuff, similar to current blood pressure cuffs, had already been invented,5 and Korotkov had brought an inflatable sphygmomanometer with him to Harbin. While previous doctors had already described how this cuff could be used to measure blood pressure, they based their measurements off the oscillations in the gauge’s needle caused by the pumping blood. Korotkov needed a more sensitive method to detect lower blood pressures than what would result in the oscillation of the needle. He began experimenting with the blood pressure cuff on injured soldiers, and out of curiosity started listening to their arteries with a stethoscope. As he inflated and deflated the cuff he could hear a dull thud in his ears, loud at first and then vanishing away as the pressure was released. He realized that he was hearing the blood flowing through the soldiers’ arteries. Intrigued, he began to listen systemically to the arteries of the injured limbs, listening for blood to flow freely in the affected areas.6 While some at the time believed that these sounds were simply echoes of the heart valves closing, Korotkov correctly deduced that the sound corresponded to the pressure waves inside the vessels which, when matched with the pressure readings on the gauge of the sphygmomanometer, could accurately assess blood pressure.2

As the war ground on, Korotkov returned to Moscow to complete some animal experiments to confirm his new theory and present his findings. On December 13, 1905, he explained his observations to a crowd of physicians. From there his idea set off a flurry of studies and his work became famous worldwide. However, as his star was rising, troubles were on the horizon for his homeland. Less than a month later, a group of unarmed protesters were gunned down by the Imperial Guards in Saint Petersburg, setting off unrest all over the country. Later that January, the Russian army would face a major defeat by the Japanese and then another. Russia would sign a peace treaty that same year, while revolutions began building at home.

Korotkov continued to work in military hospitals, but Russia, soon after ending an internal rebellion in 1905, was back at war, this time on their Western border. This young man from the small town of Kursk had spent much of his adult life at war and had made a career out of it. World War I would leave even more Russians dead, and would lead to the October Revolution which toppled the Russian monarchy. As a new government was installed, Korotkov returned from the front to Saint Petersburg, now called Petrograd, where he had first practiced as a young doctor. His career had been made by his experiences at war, and by his ability to listen. He discovered sounds within our own bodies that could be used to diagnose and heal. In 1917 Russia changed from within — the monarchy had missed the warning sounds of its own people and paid the price. Korotkov was now living in a new world, with new ideas, but he would not be a part of the new Soviet age. In 1920 at the age of 46, Korotkov passed away. A brief life,b that has affected medical practitioners around the world, because he heard something that no one else could.

On the scales of tin fish

I spoke the words of new lips

And you

A nocturn play

Could you

On the city’s drainpipes?

-Mayakovsky, And Could You, 1913c

References

- Blok AA, Woodward JB. Izbrannai︠a︡ poėzii︠a︡ = Selected poems. Bristol: Bristol Classical Press; 1992.

- Shevchenko YL, Tsitlik JE. 90th Anniversary of the Development by Nikolai S. Korotkoff of the Auscultatory Method of Measuring Blood Pressure. Circulation. July 1996. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/01.CIR.94.2.116. Accessed October 23, 2018.

- Boxer Rebellion | Significance, Combatants, & Facts. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Boxer-Rebellion. Accessed October 23, 2018.

- The Literature of the Russo-Japanese War, I. Am Hist Rev. 1911;16(3):508-528. doi:10.2307/1834835

- Care M of H. World Health Day 2013 – A short history of sphygmomanometers and blood pressure measurement. Mus Health Care Blog. April 2013. https://museumofhealthcare.wordpress.com/2013/04/07/world-health-day-2013-a-short-history-of-sphygmomanometers-and-blood-pressure-measurement/. Accessed October 23, 2018.

- Segall HN. How Korotkoff, the Surgeon, Discovered the Auscultatory Method of Measuring Arterial Pressure. Ann Intern Med. 1975;83(4):561. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-83-4-561

End Notes

- Translated from the original Russian by Joseph deBettencourt

- It is worth noting that “korot” in Russian means “short” or “brief”

- Translated from the original Russian by Joseph deBettencourt

Image Credit

- By Unknown – Shevchenko YL, Tsitlik JE, Korotkoff NS. 90th Anniversary of the development by Nikolai S. Korotkoff of the auscultatory method of measuring blood pressure. Circulation. Jul 15;94, 2, 116-8. 1996. PMID 8674166., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3820784

- Photo by Victor Bulla. Circa January 1905. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Soldiers_marching,_1st_Russian_army,_Russo-Japanese_War,_photo_Victor_Bulla.png

JOSEPH DEBETTENCOURT, is a medical student at Rush Medical College in Chicago, Illinois, with an interest in pediatrics. He attended Northwestern University where he received a BA in Theatre and Pre-Medical Studies. He has worked as a professional actor, designer, and carpenter, as well as a standardized patient, and medical researcher.

Fall 2018 | Sections | Nephrology & Hypertension

Leave a Reply