Hugh Tunstall-Pedoe

Dundee, Scotland

Mithridates VI of Pontus (136-63 BC), a formidable enemy of the Roman Empire, was vanquished after several wars. Intrigue and treachery in pursuit of power were then commonplace. Following the poisoning of his uncle, he usurped, imprisoned, or murdered his mother and other relatives, and used knowledge of poisons for attack and defense. Labeled “The Poison King”, he dosed himself to increase his tolerance.1

In past times poison and witchcraft created terrors and myths, both promoting and explaining sudden deaths. Even now some poisons are claimed to be instantaneous, infallible, and undetectable. Medieval potentates employed priests, magicians, and apothecaries for attack, and food-tasters for defense. Modern poisoners choose measured doses of one or more drugs. Back then, poison draughts, particularly those employing witchcraft, might be mixtures of nasties with magic spells. Survival of the victim was a dreaded complication; dead men tell no tales.

Exaggerations of potency persist. Berries of Atropa belladonna, “deadly nightshade”, give children unpleasant symptoms but are not necessarily fatal, even without treatment.2 Atropine, the main alkaloid, is an antidote to other poisons – a “goody” as well as a “baddy”. How fatal the bite of a “deadly” snake will be depends on the fullness of the venom glands and the completeness of the bite. Poisoned arrows succeed by slowing game down so the hunter can pursue and kill the animal, not necessarily through rapid death.

Poison is a weapon of terror, but unlike sniper-fire, inaccurate – the Amazonian rain-forest archers’ poisoned arrows are exceptional. Shakespeare used poison in several plays ending tragically, in what were also comedies of errors, with leading characters self-poisoning on receiving false news, or poisoning others by mistake, the principals all dead by the final curtain. In The Tragedy of Hamlet,3 Hamlet’s father was targeted by poison poured into his ear when asleep (a scene which left your narrator as a child covering his ears with his bedclothes). The finale of Hamlet sees two people dead from a drink meant for one, and two dead from a poisoned sword blade also meant for one. The presumed rapidity of action of poisons owes much to Shakespeare, if not Sherlock Holmes, and other fiction.

Poisoning of water supplies is an ancient weapon – but is it truly poisonous, or simply too disgusting to drink? Poison gas is a modern innovation, but problematic. Germans are credited with the first major successful use in World War I, unwisely, as they were fighting against the prevailing wind on the western front.4 Poison gas in the open is unpredictable, but effective in low-lying and confined places such as trenches and basements, streets and gas-chambers. Army veterans occupied medical beds at Guy’s Hospital, London where I studied in the 1960s, blaming their chest disease on poison gas exposure five decades earlier. They smoked high-tar cigarettes and were victims of World War I in another way, acquiring addiction to a slow-acting poison, tobacco, not from Germany, but from Virginia, USA.

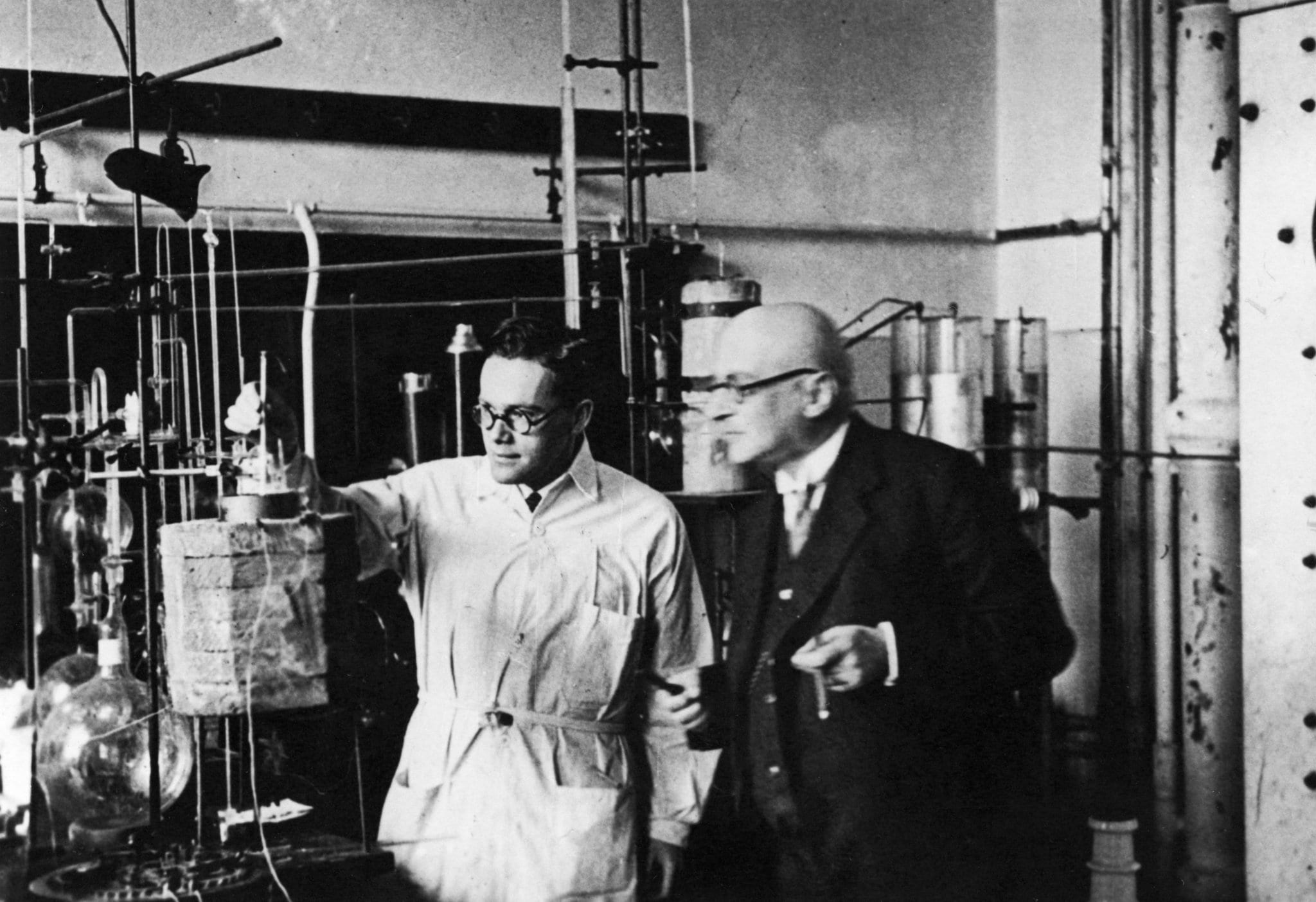

Poison gas created widespread revulsion. Fritz Haber, a Jekyll and Hyde chemical genius, industrialized mass production of fertilizer for agriculture, later winning a Nobel Prize, but also of poison gas in World War I. His wife committed suicide after finding out what he had done.5 When countered by protective apparel, gases in use at that time made a limited contribution to casualty lists, although widely used. The end of the war found their banning opposed by such as Winston Churchill.6 He championed airpower with poison gas to limit belligerent casualties. He urged, although opposed, use of gas when he was British Minister for War in 1919, against the Afghans invading British India, and for “peace-keeping” in Iraq. He sponsored a novel gas in support of the White Russian Army against the Bolsheviks in the civil war of 1919, before the Whites collapsed and British forces withdrew, jettisoning their poisonous munitions in the White Sea. Poison gas was banned in a Geneva protocol of 1925,7 following the precedent of that on expanding rifle bullets (dum-dums) in 1899.8

Between the wars, research and stockpiling of poison gases and their antidotes continued, with some use in various colonial wars in Africa and Asia by Spain, Italy, and Japan. With a European war imminent, every inhabitant of Britain was issued a gas mask in September 1939. The factory workers that made them developed asbestosis decades later, but poison gases were not used in battle. Both sides, including Churchill, worried about “the other fella” retaliating – mutual deterrence – although Churchill would have used gas against enemy troops invading Britain. After trying carbon monoxide, the Germans used Zyclon B in gas chambers on Jewish civilians in the Holocaust, a gas tragically developed earlier by Fritz Haber (by then deceased), a Jewish convert to Christianity, nevertheless persecuted by the Nazis before he died.5 During the Cold War, poisonous munitions re-accumulated, including nerve agents, and were allegedly destroyed later following another Convention in 1993.9

Poison gases and poisons have reappeared on the international scene: the former through nations holding international conventions in contempt, abetted by cynical sabotage of emergency resolutions at the United Nations Security Council; the latter through secret services carrying out revenge against nationals evading their clutches in foreign countries. Western countries bomb identified terrorists with drones in war-torn countries, while some other nations feel entitled to assassinate their dissidents who find sanctuary abroad.

A vindictive autocrat possessing novel poisons is tempted to use them on renegade citizens in their place of refuge – a double whammy, or as Voltaire put it ‘pour encourager les autres’.10 Victims are threatened in advance, to intimidate them and others. Ideally for the autocrat, the origin is suspected, but the poison and its source are unproven – so no criminal trial is possible.

Georgi Markov,11 a Bulgarian critic of the president when Bulgaria was a Soviet satellite, broadcast for the BBC World Service in London for many years. He claimed he was stabbed with an umbrella in 1978 when crossing Waterloo Bridge in London, and died soon after. A similar episode in Paris revealed a pellet containing ricin, a dangerous toxin. Soviet dissidents cited KGB provenance. Interest in ricin led to the development of cytotoxic agents for treating cancers, “beating swords into ploughshares”.12

Alexander Litvinenko13 a member of the Russian secret service, became disillusioned by plots to murder a prominent oligarch, and the bombing of Russian cities – seemingly promoting the candidacy of Vladimir Putin for president.14 He escaped to Britain. In 2006 he became mortally ill after drinking tea with Russian contacts. It was two weeks before the responsible cytotoxic agent was identified as polonium, a radioactive element first discovered by Marie and Pierre Curie, not detectable by conventional Geiger-counters.15 Investigation revealed a trail of such radioactivity across multiple sites in London visited by his poisoners, and even their plane from Moscow. Signature impurities specified the nuclear reactor where polonium was produced.13 Moscow refused extradition of the chief suspect, and decorated him.

Sergei Skripal16 was likewise a disillusioned member of the Russian secret service taking refuge in Britain, subjected to exotic poisoning in 2018. His illness, along with that of his daughter and a local policeman, was rapidly identified by toxicologists to be from the nerve agent novichok, developed in Russia and found on the external door-handle of his house. The finding was confirmed by the international Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons.17

The reactions to the polonium and novichok poisonings by those accused are revealing. Did Russia expect the poisons not to be identified and to remain a secret? Statements from Moscow media were multiple and contradictory, suggesting no prepared, advance cover-story for being found out, reacting like a guilty child challenged for a misdemeanor. Novichok was alleged by its developer to be undetectable, inevitably fatal, and irreversible, conforming to the ancient myth of the ultimate poison.16 If the Russian secret service attempted assassination, they allegedly did it properly. Events proved otherwise. Perhaps incompetence with arrogance is an occupational hazard of cloak-and-dagger secret services. Like the trail of polonium in the Litvinenko case, the subsequent discovery, with lethal consequences, of a discarded scent-spray bottle containing novichok near the original crime scene suggests recklessness. It is reminiscent of Shakespearean tragedy in its untargeted effects.

There may be many, more competent assassinations of dissidents abroad which have not been flagged up and investigated so far, involving poison and other modalities.16 Other countries may be emulating Russian precedents. There are many potential targets. Sophistication of foreign assassinations has progressed impressively since Trotsky was murdered with an ice-axe in his hotel room in Mexico City in 1940, physically fighting for his life with his assassin.18 Hopefully the world is not turning back to Machiavelli and medieval practices.

Which brings us back to the first poisoning in this story, 2,000 years before “forensics”, which precipitated Mithridates’ trail of revenge.1 His uncle suddenly stood up during a feast, clutched his throat, collapsed and died – evidence of a powerful poison to his contemporaries, and apparently to modern historians of the classic era. But the presumed diagnosis now must be laryngeal obstruction, through inhalation of a bolus of meat, from alcohol and gluttony. Was the abdominal thrust19 known of in those far-off days, and would anyone have been allowed near the royal person to use it without being killed himself? Would Mithridates have accepted an innocent explanation for his uncle’s death, or would he have disposed of his relatives anyway, peddling the “fake news” of murder or attempted murder?

We will never know. But we need to question ancient anecdotes, as well as alleged instantaneous, undetectable poisoning, in the light of modern knowledge.

References

- Mayor A. The Poison King: the Life and Legends of Mithridates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy. Princeton University Press 2011 Princeton NJ

- https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atropa_belladonna Retrieved 14/08/2018

- Shakespeare W. The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. First folio. Edward Blount and William and Isaac Jaggard , London 1623

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chemical_weapons_in_World_War_I Retrieved 14/08/2018

- https://chemical weapons.cenmag.org/who-was –the-father-of-chemical-weapons/ Retrieved 14/08/2018

- http://spartacus-educational.com/spartacus-blogURL5.html Retrieved 14/08/2018

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geneva_Protocol Retrieved 14/08/2018

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expanding_bullet Retrieved 14/08/2018

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chemical_Weapons_Convention Retrieved 14/08/2018

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Candide Retrieved 14/08/2018

- https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/crime/9949856/Prime-suspect-in-Georgi-Markov-umbrella-poison-murder-tracked-down-to-Austria.htn Retrieved 14/08/2018

- Isaiah II. King James Authorised Bible. London 1611

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poisoning_of_Alexander_Litvinenko#Sources_and_production_of_polonium Retrieved 14/08/2018

- Litvinenko A. Blowing up Russia. Gibson Square London 2007

- https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/themes/physics.curie Retrieved 14/08/2018

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poisoning_of_Sergei_and_Yulia_Skripal Retrieved 14/08/2018

- https:www.opcw.org/ Retrieved 14/08/2018

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/sep/13/trotsky-ice-axe-murder-mexico-city-Trotsky-assassination Retrieved 14/08/2018

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abdominal_thrusts Retrieved 14/08/2018

HUGH TUNSTALL-PEDOE, MA, MD, FRCP (London and Edinburgh), FFPH, FESC, is emeritus professor and senior researcher in the Cardiovascular Epidemiology Unit, Dundee University, Scotland, UK. Trained at Cambridge University, Guy’s Hospital, and other London hospitals in clinical cardiology, Dr. Tunstall-Pedoe began work in cardiovascular epidemiology in 1969. In 1981 he was appointed to establish the Cardiovascular Epidemiology Unit in Dundee, Scotland. He worked there on the Scottish Heart Health Extended Cohort and the World Health Organization MONICA study, for which he drafted the protocol and was rapporteur for twenty-three years, leading major publications including the concluding monograph. He is the originator of two cardiovascular risk scores and has also contributed to aviation cardiology. He remains active in research while nominally retired.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 2 – Spring 2019

Leave a Reply