Anabelle S. Slingerland

Leiden, Netherlands

Kevin Brown

London, England

On April 23, 2018, Prince William and the Duchess of Cambridge left the Lindo Wing of St. Mary’s Hospital in London with their new baby boy. Fans of the Royals, who had been camping outside St. Mary’s for weeks, and the crowds and photographers who had gathered for the day, packed up. The Queen’s surgeon-gynecologist Dr. Alan Farthing, obstetrician Dr. Guy Thorpe-Beeston, and their twenty-member staff left by the back door. It was also at St. Mary’s that in 1982 Prince Charles and the Princess of Wales had welcomed their new son Prince William. Ever since surgeon-gynecologist Sir George Pinker recommended the hospital instead of the palace for the birth of the eldest child of the Duchess of Gloucester in 1974, members of the British and foreign royal families have been born in the Lindo Wing.

St. Mary’s Hospital has also had other royal connections. The Queen Mother had been president of the hospital since 1930, as well as patron of the medical school from 1954 until her death in 2002. The granddaughter of Edward VII, Princess Arthur of Connaught, was the first member of the British Royal Family to train and qualify as a nurse during the Great War. Before her marriage she had been reprimanded for revealing an ankle when bending over, but later became president of the Ladies’ Association and, in 1922, patron to the Past and Present Nurses’ League. Many hospital wings have been named after benefactors of royal ancestry, such as the Albert Edward Wing. In 1884 Princess Louise opened the Mary Stanford Wing. Even further back in time, on June 28, 1845, Prince Albert laid the foundation stone for the hospital itself on the site of the Grand Junction Waterworks Company’s reservoir.

St. Mary’s was started as a voluntary hospital to care for the sick and the poor. After the building of the Grand Junction Canal (1805) and the Great Western Railway (1837), the village of Paddington in northwest London had grown in population and had suffered from several typhoid and cholera epidemics. In 1842 an emergency meeting held at the local parochial schoolroom resulted in plans for a new hospital. The medical staff offered their services for free, and governance was in the hospital’s own hands. Progress was hampered by the death of its first builder and the bankruptcy of the second, but George Bird of the hospital committee offered his own money so that the 150-bed hospital could be opened in 1851. The hospital remained strictly a “house for the poor,” and when the organizers of the Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace asked if their French visitors could stay in the hospital for the duration of the exhibition, the hospital refused. The people themselves also contributed by raising funds for beds and cots, named in honor of their generosity. The Ladies’ Association was started in 1903 to sew bed linens for free. Later fundraising events such as flag days, bazaars, balls, race meetings, and matinees became regular hospital routine.

The hospital was also committed to teaching. The first two students were admitted in 1851, and the medical school opened three years later. For some, such as Samuel Armstrong Lane (1802-1892) who had owned a private anatomy school close to St George’s Hospital, the founding of the medical school fueled personal ambitions. He insisted on having 150 beds, the minimum requirement by the Royal College of Surgeons for a teaching facility. He also supported the building of a proper medical school, as required by the Society of Apothecaries for a teaching hospital. For physicians with large, flourishing West End private practices, it was a matter of professional prestige and honor to serve as unpaid honorary members of staff at a teaching hospital in a poor area. The staff included many royal physicians and surgeons, presidents of the Royal Colleges, and fellows of the Royal Society. Hospital rounds were often conducted by a large team consisting of a physician or surgeon, a registrar, the houseman, a consultant, nurses, clerks, and dressers. For those with research interests, St. Mary’s was a rich place to grow in knowledge and experience.

Another commitment and dedication was St. Mary’s nursing: the first matron, Mrs. Alicia Wright, learned by experience under harsh working conditions, working long hours from 6am till 10pm with little if any sleep. Florence Nightingale’s protégé Rachel Williams came in 1876 to professionalize nursing. Later the hospital was provided with a school to train nurses. This became even more important during the Great War, when Mary Milne became well-respected as the sector matron, having been the first sister tutor in South Africa.

At the end of World War I, Charles Wilson, later Lord Moran, turned his frontline experience into a military cross and a series of lectures on resilience, publishing his description of the trenches in his famous book The Anatomy of Courage. The shortage of medical students during the war resulted in women being admitted as students for the first time; in 1916, students from the London School of Medicine for Women were allowed to complete their clinical studies at the hospital. Women continued to fill the junior posts until 1924, were allowed again in 1947 to train at the hospital, and in 1971 the first woman was appointed to the medical staff. In 1920 Charles Wilson became dean of the Medical School, bringing together his organizational and writing skills with his passion for rugby, even linking admission to the medical school to prowess in playing the game.

In World War II the hospital served as a clearing station for air-raid casualties. It suffered no major damage on 20 February 1944 despite a heavy barrage of firebombs that medical students on fire-watching duties pushed off the roof. During the war, Lord Moran became Winston Churchill’s physician and later wrote a famous and somewhat controversial account of his patient’s medical history. In 1959 Lady Churchill opened the new Winston Churchill Wing at St. Mary’s.

St. Mary’s also has a long history of scientific research and contributions to medicine. Augustus Desire Waller (1856-1922) worked there in physiology, studied the electrical impulses of the heart, and developed the first electrocardiogram. Sir Almroth Wright (1861-1947), the professor of pathology who developed the first British typhoid vaccine, was a controversial person satirized by Bernard Shaw in Doctor’s Dilemma. Also at St. Mary’s were Cecil Alport (hereditary nephritis associated with deafness, 1927); Zachary Cope (“Early Diagnosis of the Acute Abdomen”, 1921); Arthur Dickson Wright (surgeon and also a riveting after-dinner speaker); Charles Rob (kidney transplantation); Felix Eastcott (carotid endarterectomy); Rodney Porter (structure of antibodies); George Pickering (hypertension); Stanley Peart (structure of angiotensin); and Roger Bannister (ran the mile under four minutes and became a distinguished neurologist).

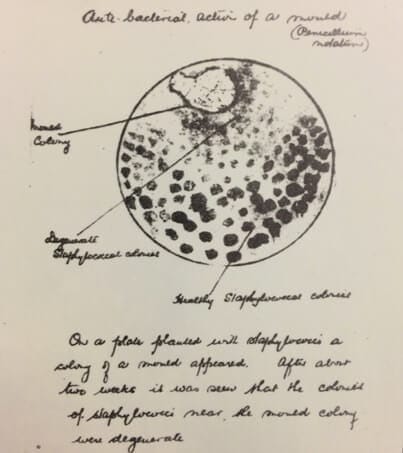

In 1928, in a small simple laboratory in the Clarence Wing of the hospital, Alexander Fleming carried out his experiments that led to the discovery of penicillin, observing that a Petri dish inoculated with Staphylococci had been contaminated with a mold. The mold juice, as he called it, had inhibited bacterial growth around it, showing a distinct zone of inhibition. His assistant Stuart Craddock tasted the mold and said it resembled Stilton cheese: it did not harm him but also did not help his sinusitis. With the assistance of Frederick Ridley, who had some knowledge of chemistry, they discovered that the mold juice would kill bacteria but not human tissue. Their results were published between 1929 and 1944. In World War II, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain worked to develop the drug at Oxford and modern mass production methods got underway in the United States, saving thousands of lives and revolutionizing the treatment of infectious diseases.

In 1948 St. Mary’s was brought under the governance of the newly formed National Health Service (NHS) and the medical school became independent of the hospital. Over time, St. Mary’s Teaching Group of Hospitals included the Samaritan Free Hospital for Women (founded 1847), the Western Ophthalmic Hospital (founded 1856), the Paddington Green Children’s Hospital (founded 1883), Bells Street Dispensary (founded 1862), the Princess Louise Kensington Hospital for Children (founded 1840), St Luke’s Hospital, Bayswater (founded 1893), Hereford Lodge hospice (founded 1893), and the Paddington General Hospital at Harrow Road.

At present St Mary’s Hospital is one of five hospitals under the NHS Imperial College of London. It has served royalty and ordinary people alike. The Ladies’ Association has continued in the form of Friends of St Mary’s Hospital and still reflects its charitable mission. St. Mary’s Hospital Archives and the impressive Alexander Fleming Laboratory Museum have been designated an International Historic Chemical Landmark, celebrating St. Mary’s role in the historic development of penicillin.

Further reading

- St. Mary’s, the history of a London teaching hospital. E.A.Heaman. Liverpool University Press.St. Mary’s Hospital, an illustrated history, K. Brown. London W2.

- St. Mary’s Hospital, 1991, Kevin Brown, ISBN 0951838709.

- Churchill’s Doctor, a Biography of Lord Moran, Richard Lovell, Royal Society of Medicine Services Ltd, 1st edition, 1994.

- Alexander Fleming Laboratory Museum, a guide, K. Brown, ISBN 0951838733, St. Mary’s NHS Trust 2000.

- Alexander Fleming. On the Antibacterial Action of Cultures of a Penicillium, with Special Reference to Their Use in the Isolation of B. Influenzae, British Journal of Experimental Pathology, vol 10, pages 22fS236, 1929.

- Alexander Fleming and the development of penicillin, Alexander Fleming Laboratory Museum Education Resource pack, St Mary’s NHS Trust, 2000, edited and compiled by K. Brown, ISBN 0951838725.

- Alexander Fleming, The Discovery of Penicillin, British Medical Bulletin, Volume 2, Issue 1, 1 January 1944, pages 4-5.

- Hospitals & Nursing 1845-1948, A Century of Healthcare at St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington, St Mary’s Hospital Archives Education Resource pack, edited by K. Brown, ISBN 0951838717.

- Fleming Discoverer of Penicillin, J.L. Ludovici, published by A. Dakers, first edition, 1952.

- Obituary, Sir Alexander Fleming, Robert Cruickshank, Journal of Clinical Pathology, 8, 355, 1955.

- The Discovery of the chemotherapeutic properties of penicillin. E.Chain, H.W. Florey. British Medical Bulletin. Vol 2, Issue 1, January 1, 1944, pages 5-7.

- Penicillin Man: Alexander Fleming and the Antibiotic Revolution, K. Brown, Sutton Publishing, 2004.

ANABELLE S. SLINGERLAND, MD, DSc, MPH, MScHSR, received her medical degree from Amsterdam University and Amsterdam University Medical Center, her degrees in Public Health, Health Services Research and Genetics from the Erasmus University in Rotterdam, and has authored and co-authored papers on monogenic diabetes.

DR. KEVIN BROWN is archivist at St Mary’s and leads the archivist research as well as the Alexander Fleming Museum.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 2 – Spring 2019