Sarah Riedlinger

Dean Giustini

Brenden Hursh

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Introduction

|

| The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, 1929. Photo credit: Toronto Public Library, Accession # tspa_0113248f |

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the most common chronic diseases in the world.1 In 2009 Canada alone had 2.35 million people with diabetes.2 Some 10% of sufferers have type 1 diabetes (T1DM), the most common form seen in children.3 Before 1922 most children with diabetes died, as shown by the case report of a two-year-old girl treated by physician Lionel Lindsay at the Montreal Children’s Hospital in 1917:4

“[She had] lost her appetite except for sweets and drank large quantities of water. . . . Her skin was loose, dry and harsh. . . . Her tongue was dry and coated, her breath had a sweetish odour. The abdomen was scaphoid. The heart and lungs were apparently normal. She was fretful and irritable. Weight 26 pounds.”5

Pale and under-nourished, she was hospitalized for forty-seven days. She was discharged only to be re-admitted two months later and died on her second admission.6

In his personal journals, Banting stated that the life expectancy of childhood diabetes before 1922 was a matter of months.7 After the advent of insulin the mortality in patients under twenty years old in Canada and the United States (US) declined spectacularly.8 The stories of children under Banting’s care during the 1920s at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children underline the historical significance of insulin and the important difference it made for millions of patients.

Treatment for type 1 DM before the discovery of insulin

T1DM is an autoimmune disease in which auto-antibodies attack pancreatic cells causing an absolute insulin deficiency.9,10 The difference between the two types of diabetes was first elucidated in 1936 by Sir Harold Himsworth as insulin-sensitive (T1DM) and insensitive (T2DM).11 Their characteristic symptoms of polyuria and polydipsia are the same, leading to the broader recognition of diabetes as a disease entity before it was sub-classified. For millennia it seemed to have an intractable prognosis, leaving physicians helpless to change its inexorable course.

Some treatments for diabetes date back to the eighteenth century. Though mostly ineffective, they kept some patients alive for a short time. In 1797 the Scottish physician John Rollo prescribed an animal diet of “plain blood pudding” and “fat and rancid meat.”12 Various diets were prescribed and opium was used to dull the pain. In the early twentieth century, the American physician Elliot Joslin was a leader in diabetes care in the US.13, 14 Between 1915 and 1922, he and his colleague Frederick M. Allen used starvation diets as first line treatment.15 One of Allen’s patients, an eleven-year-old girl named Elizabeth Hughes, was treated with a 500 calorie per day diet. Her weight decreased from 75 to 55 pounds, endangering her life. Hughes would eventually become one of Banting’s most famous patients.16 In The Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus, Joslin reported a reduction in mortality of about 20%, but much of his work was presented anecdotally with no quantitative data.17, 18

Given the absence of effective alternatives, insulin was quickly mass produced and widely distributed after its discovery.19 No randomized control trial was ever conducted to justify its use, and withholding treatment would have been considered unethical.

The discovery of insulin

In October 1920, Banting read a paper titled “Relation of the Islets of Langerhans to Diabetes with Special Reference to Cases of Pancreatic Lithiasis” in Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics.20 This article gave him the idea to ligate the pancreatic ducts of dogs, allow the digestive enzymes degenerate over six to eight weeks, and then extract intact islets cells.21, 22 But Banting had little experience in laboratory medicine, and needed the assistance of someone with knowledge of physiology, prestige, and the necessary funds to pursue his line of inquiry.

Banting sought the help of John James Rickard Macleod, professor of physiology at the University of Toronto, who provided him with laboratory space and supplies, and introduced him to his research assistant Charles Herbert Best. They began their experiments in May 1921, removing pancreatic extracts from live dogs and administering them to other dogs made diabetic by removing their pancreas. Most dogs died but some lived.23, 24, 25 Yet even that success was frustrating; despite keeping some dogs alive, they had not identified the substance responsible for the anti-diabetic effects.

|

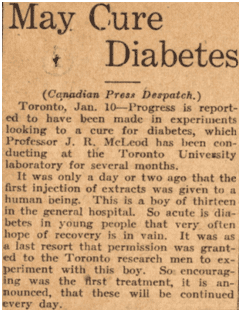

| Canadian Press, “May Cure Diabetes” 10 January 1922.31 |

In December 1921, Macleod recruited James Bertram Collip, a biochemist from the University of Alberta, to aid his team. Collip developed a method to precipitate purified insulin by using various concentrations of acidic alcohol on beef pancreases.26, 27 After nearly ten months of experiments, their extract was ready to be tested on a human subject.

The first human injection of insulin

On 2 December 1921, an emaciated fourteen-year-old Leonard Thompson arrived at the Toronto General Hospital’s emergency department. He had been diagnosed with diabetes two years earlier and had survived by careful diet regulation.

In a desperate effort to save him, Thompson’s parents consented for him to be the first patient to receive insulin by injection. On 11 January 1922, the first injection dropped his blood glucose levels by 25% but failed to clear his urine of glucose. During the next twelve days, Collip worked to develop a stronger formulation. Daily injections were given to Thompson between 23 January and 4 February.28 The stronger injections continued to drop his blood glucose and by 25 January glucose was no longer present in his urine.

By February 1922, six other patients had been given the extract with the same positive results.29 Banting, Best, and Collip were named as authors on their original paper “Pancreatic extracts in the treatment of diabetes mellitus” in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.30

News of Banting and Best’s discovery spread quickly. By late 1922 the researchers were receiving letters from many patients with pleas for help.32 Previously diabetes had been a disease with no effective treatment, but now children suffering from it were revived from near death. Insulin therapy allowed once malnourished, fragile children to regain their strength and lead normal lives. Macleod began to call insulin “the greatest thing of the age” and Toronto newspapers shared patients’ personal success stories of being saved by insulin.33 The local newspapers generated headlines such as “Hope that Insulin is Permanent Cure.” For their discovery, Banting and Macleod were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1923.34 In a show of magnanimity, Banting shared his prize with Best and Macleod shared his with Collip; however, the events leading to the discovery of insulin left tension, resentment, and permanent rifts between the researchers.

End notes

- See Public Health Agency of Canada, Diabetes in Canada: Facts and Figures from a Public Health Perspective, Ottawa, Ontario: Government of Canada, 2011, pp. 79.

- Ibid., 14.

- Canadian Diabetes Association, Diabetes: Canada at the Tipping Point – Charting a New Path, [2011], Accessed 15 Feb 2018: http://www.diabetes.ca/CDA/media/documents/publications-and-newsletters/advocacy-reports/canada-at-the-tipping-point-english.pdf.

- Lionel M Lindsay, “Diabetes Mellitus in a Child of Three”, Canadian Medical Association Journal, 7, no. 2 (1917): 133-5.

- Ibid., pp. 133.

- Ibid., pp. 133.

- University of Toronto, Fisher Library Digital Collections, F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers. Banting Scrapbooks, Scrapbook 1, pp. 34, 35. Accessed 15 Feb 2018 https://resource.library.utoronto.ca/insulin/scrapbooks.cfm

- Edwin A. M Gale, “The Rise of Childhood Type 1 Diabetes in the 20th Century”, Diabetes, 51, no. 5 (2002): 3353-3361.

- Kathleen M Gillespie, “Type 1 Diabetes: Pathogenesis and Prevention”, Canadian Medical Association Journal 175, no. 2 (2010): 165-170.

- Kathleen M Gillespie, “Type 1 Diabetes: Pathogenesis and Prevention.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 175, no. 2 (2010): 165-170.

- H. P. Himsworth, “Diabetes Mellitus: Its Differentiation into Insulin-Sensitive and Insulin-Insensitive Types. 1936.” International Journal of Epidemiology 42, no. 6 (2013): 1594-1598.

- Diabetes Canada. [First screen]. Accessed 15 Feb 2018 http://www.diabetes.ca/about-diabetes/history-of-diabetes.

- E. P. Joslin, “The Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, 14, no. 9 (Sep 1924): 808-811.

- E. P. Joslin, “The Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus,” Canadian Medical Association Journal 6, no. 8 (Aug 1916): 673-684.

- Allan Mazur, “Why were “Starvation Diets” Promoted for Diabetes in the Pre-Insulin Period?”, Nutrition Journal, 10, no. 1 (2011): 23-23.

- Ibid.

- Joslin, 1924.

- Mazur, 2011.

- Bliss, 1993.

- Moses Barron. The relation of the islets of Langerhans to diabetes with special reference to cases of pancreatic lithiasis. Franklin H. Martin Memorial Foundation, 1920.

- Louis Rosenfeld, “Insulin: Discovery and Controversy,” Clinical Chemistry, 48, no. 12 (2002): 2270-2288.

- Frederick Banting, “Further Clinical Experience with Insulin (Pancreatic Extracts) in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus,” British Medical Journal, 1, no. 3236 (1923): 8-12.

- Rosenfeld, 2002.

- Bliss, 1993.

- Banting, 1923.

- Bliss, 1993.

- Banting, 1993 reprint.

- Banting, 1923.

- Banting, 1923.

- Frederick Banting, Charles H. Best, JB Collip, WR Campbell, AA Fletcher, “Pancreatic Extracts in the Treatment of X Diabetes Mellitus,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, 12, no. 3 (1922): 141-146.

- Canadian Press, “May Cure Diabetes,” Toronto Star, 10 January 1922.

- University of Toronto. F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers D. Banting Scrapbooks, Scrapbook 1, pp. 34, 35. Accessed 15 Feb 2018 https://resource.library.utoronto.ca/insulin/scrapbooks.cfm

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

References

- Allan, Frank N. “Diabetes before and after insulin.” Medical History 16, no. 3 (1972): 266-273.

- Diabetes Canada. Accessed 15 Feb 2018 http://www.diabetes.ca/about-diabetes/history-of-diabetes.

- Diapedia. Accessed 15 Feb 2018 https://www.diapedia.org/type-1-diabetes-mellitus/2104085152/discovery-of-type-1-diabetes.

- Banting, Frederick. “Further Clinical Experience with Insulin (Pancreatic Extracts) in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus.” British Medical Journal 1, no. 3236 (1923): 8-12.

- Banting, Frederick, Charles H. Best, JB Collip, WR Campbell, AA Fletcher. “Pancreatic Extracts in the Treatment of X Diabetes Mellitus.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 12, no. 3 (1922): 141-146.

- Baum, J. D. “Home Monitoring of Diabetic Control.” Archives of Disease in Childhood 56, no. 12 (1981): 897-899.

- Barron, Moses. The relation of the islets of Langerhans to diabetes with special reference to cases of pancreatic lithiasis. Franklin H. Martin Memorial Foundation, 1920.

- Bliss, Michael. “The History of Insulin.” Diabetes Care 16 (1993): 495-503.

- Bliss, Michael. The Discovery of Insulin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982.

- Boyd, Gladys L. “The Treatment of Diabetes in Children.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 42, no. 5 (1940): 438-442.

- Boyd, Gladys L. “The Treatment of Diabetic Coma in Children.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 21, no. 5 (1929): 520-523.

- Boyd, Gladys L. “Course and Prognosis of Diabetes Mellitus in Children.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 17 (1927): 1167-72.

- Boyd, Gladys L. “Insulin Treatment in Diabetes in Children.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 14, no. 1 (1923): 33-40.

- Canadian Diabetes Association. Diabetes: Canada at the Tipping Point – Charting a New Path, [2011]. Accessed 15 Feb 2018 https://www.diabetes.ca/CDA/media/documents/publications-and-newsletters/advocacy-reports/canada-at-the-tipping-point-english.pdf.

- Canadian Press. “May Cure Diabetes.” Toronto Star., 10 January 1922.

- Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT). “The Effect of Intensive Treatment of Diabetes on the Development and Progression of Long-Term Complications in Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus.” New England Journal of Medicine 329, no. 14 (1993): 977-86.

- Fry, Andrew. “Insulin Delivery Device Technology 2012: Where are we After 90 Years?” Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology 6, no. 4 (2012): 947-53.

- Gale, Edwin A. M. “Historical Aspects of Type 1 Diabetes.” Diapedia: The Living Textbook of Diabetes. August, no. 13 (2014): https://www.diapedia.org/type-1-diabetes-mellitus/2104085134/historical-aspects-of-type-1-diabetes-https://www.diapedia.org/type-1-diabetes-mellitus/2104085134/historical-aspects-of-type-1-diabetes.

- Gale, Edwin A. M. “The Rise of Childhood Type 1 Diabetes in the 20th Century.” Diabetes 51, no. 5 (2002): 3353-3361.

- Gemmill, Chalmers L. “The Greek Concept of Diabetes.” Bulletin of the New York Academic of Medicine 48, no. 8 (1972): 1033-36.

- Gillespie, Kathleen M. “Type 1 Diabetes: Pathogenesis and Prevention.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 175, no. 2 (2010): 165-170.

- Himsworth, H. P. “Diabetes Mellitus: Its Differentiation into Insulin-Sensitive and Insulin-Insensitive Types. 1936.” International Journal of Epidemiology 42, no. 6 (2013): 1594-1598.

- Joslin, E. P. “The Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 14, no. 9 (Sep 1924): 808-811.

- Joslin, E. P. “The Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 6, no. 8 (Aug 1916): 673-684.

- Lindsay, Lionel M. “Diabetes Mellitus in a Child of Three.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 7, no. 2 (1917): 133-5.

- Mazur, Allan. “Why were “Starvation Diets” Promoted for Diabetes in the Pre-Insulin Period?” Nutrition Journal 10, no. 1 (2011): 23-23.

- Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine 1923. Frederick G. Banting, John Macleod. Nobel Lecture, September 15, 1925. Diabetes and Insulin. Accessed 15 Feb 2018. https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1923/banting-lecture.html

- Pickup, J. C. “Banting Memorial Lecture 2014 Technology and Diabetes Care: Appropriate and Personalized.” Diabetic Medicine 32, no. 1 (2015): 3-13.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Diabetes in Canada: Facts and Figures from a Public Health Perspective. Ottawa, Ontario.: Government of Canada., 2011.

- Quianzon, Celeste C., and Issam Cheikh. “History of Insulin.” J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2, no. 2 (2012): 1-3.

- Rosenfeld, Louis. “Insulin: Discovery and Controversy.” Clinical Chemistry 48, no. 12 (2002): 2270-2288.

- Roth, Jesse, Sana Qureshi, Ian Whitford, Mladen Vranic, C. Ronald Kahn, I. George Fantus, and John H. Dirks. “Insulin’s discovery: new insights on its ninetieth birthday.” Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews 28, no. 4 (2012): 293-304.

- The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids). Toronto. “About SickKids. Timeline: 1901-1925.” Accessed 15 Feb 2018. http://www.sickkids.ca/AboutSickKids/History-and-Milestones/Milestones/1901-1925/index.html.

- University of Toronto. Fisher Library Digital Collections. “1920-1925. the Discovery and Early Development of Insulin. ” Accessed 15 Feb 2018https://resource.library.utoronto.ca/insulin/index.html.

- University of Toronto. Fisher Library Digital Collections. “Letter to Dr. Banting Ca. 1923. Ryder, Teddy (Theodore). MS. COLL. 76 (Banting), Box 8B, Folder 11. ” Accessed 15 Feb 2018. https://resource.library.utoronto.ca/insulin/digobject.cfm?idno=L10021&Page=0001&size=1&query=ryder&searchtype=fulltext&searchstrategy=all&startrow=1&media=all&sort=date_asc&photo=on&refine=no&transcript=

off#bibrecord - University of Toronto. Fisher Library Digital Collections. “Patient Records for Leonard Thompson. MS. COLL. 76 (Banting), Box 8B, Folder 17B. Dec 1921 – Jan 1922. ” Accessed 15 Feb 2018. https://resource.library.utoronto.ca/insulin/digobject.cfm?idno=M10015&Page=0001&size=2&query=toronto%20AND%20general%20AND%20hospital&searchtype=fulltext&searchstrategy=all&startrow=1&media

=all&sort=date_asc&photo=on&transcript=off&refine=no. - University of Toronto. Fisher Library Digital Collections. “Photograph of Teddy Ryder, 10/07/1922. Original Photograph Showing Teddy Ryder when He First Arrived in Toronto Weighing 27 Pounds.” Accessed 15 Feb 2018. https://resource.library.utoronto.ca/insulin/digobject.cfm?idno=P10037&Page=0001&size=1&query=ryder&searchtype=fulltext&searchstrategy=all&startrow=1&media=all&sort=date_asc&photo=on&refine=no&transcript=

off#bibrecord - University of Toronto. Fisher Library Digital Collections. F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers. Banting Scrapbooks, Scrapbook 1, pp. 34, 35. Accessed 15 Feb 2018.

- University of Toronto. Fisher Library Digital Collections. F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers. “Insulin method saves Galt girl”. [October 1922]. MS. COLL 76 (Banting) Scrapbook 1, Box 1, Page 88. Accessed 15 Feb 2018. https://insulin.library.utoronto.ca/digobject.cfm?idno=C10113&Page=0001&size=1&query=Elsie%20AND%20Needham&searchtype=fulltext&searchstrategy=All&startrow=1&media=all&sort=title_sort&photo=

on&transcript=off&refine=no - University of Toronto. Fisher Library Digital Collections. F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers. Letter to F. G. Banting 01/01/1923. Hughes, Elizabeth Evans. MS. COLL. 76 (Banting), Box 8A, Folder 26A. Accessed 15 Feb 2018. https://resource.library.utoronto.ca/insulin/digobject.cfm?idno=L10017&Page=0001&size=1&query=elizabeth%20AND%20hughes%20AND%20letter&searchtype=fulltext&searchstrategy=all&startrow=1&media=

all&sort=title_sort&photo=on&transcript=off&refine=no - University of Toronto. Fisher Library Digital Collections. F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers. Letter to mother 22/08/1922. Hughes, Elizabeth Evans. Original not in Fisher Collection MS. COLL 334 (Hughes) Box 1, Folder 35A. Accessed 15 Feb 2018. https://insulin.library.utoronto.ca/digobject.cfm?idno=L10006&Page=0001&size=1&query=Ruth%20AND%20Whitehill&searchtype=fulltext&searchstrategy=all&startrow=1&media=all&sort=title_sort&photo=

on&transcript=off&refine=no - University of Toronto. Fisher Library Digital Collections. F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers. Letter to Dr. Banting 02/11/26. Hughes, Elizabeth Evans. MS. COLL. 76 (Banting), Box 8A, Folder 26A. Accessed 15 Feb 2018. https://resource.library.utoronto.ca/insulin/digobject.cfm?idno=L10018&Page=0001&size=1&query=elizabeth%20AND%20hughes%20AND%20letter&searchtype=fulltext&searchstrategy=all&startrow=1&media=

all&sort=title_sort&photo=on&transcript=off&refine=no - Vipond, Mary. “A Canadian Hero of the 1920s: Dr. Frederick G. Banting.” Canadian Historical Review 63, no. 4 (1982): 461-486.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our thanks to the University of Toronto Banting Archives, especially to archivists Jacob Keszei and Jennifer Toews, for assisting us in locating multiple resources and documents from the Fisher Library Digital Collections and the Banting and Best fonds.

SARAH RIEDLINGER, BSc (Hon), MD, is a Pediatric Resident in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

DEAN GIUSTINI, MLS, MEd, is a Biomedical Branch Librarian at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver Canada.

BRENDEN E. HURSH, MD, MHSc, FRCPC, is a doctor in the Endocrinology & Diabetes Unit at British Columbia Children’s Hospital and the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

Spring 2018 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply