Jesús Ramírez-Bermúdez

Translated by Ilana Dann Luna

Mexico City, Mexico

|

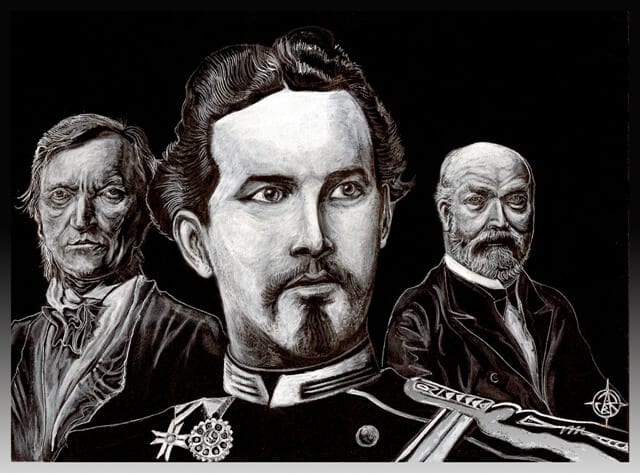

| The Monarch, The Musician and the Medic, Jose Agustin Ramirez Bermudez. Location: Jesus Ramirez Bermudez Private Collection |

The history of medicine bestows us with unexpected episodes, such as the character of “The Swan King,” whose platonic love for a disgraced musician sparked the artistic transformation of a kingdom. A physician’s intervention led to a tragic scene in a castle by a lake, where a chapel now stands in memory of the following story:

The Monarch and the Musician

Maximillian II, King of Bavaria, died in 1864, leaving the throne to his eighteen-year-old son: Louis II, known in England as “The Swan King,” and in Germany as “The King of Fairy Tales.” Louis II’s heart belonged to the world of the arts.1 His imagination had been nourished by Richard Wagner’s grandiose operatic sentiments, and one of his first acts of government was to find the musician, who was on the run and hiding from his creditors, and who, in spite of his fame, lived in economic destitution. Two months after his assumption of power, the King granted a royal audience of extremely unusual length to the musician. They discussed how to give Bavaria the grandeur of a Wagnerian opera. A year after that initial visit to the court, with the King’s patronage, Wagner presented his work Tristán e Isolda with great success in Munich. However, the musician’s conduct, judged to be scandalous by the conservative elites of Bavaria, forced King Louis II to banish Wagner from the city. It is said that the King seriously considered stepping down from his throne to follow his idol, but Wagner convinced him to remain in power.

Louis II dedicated himself to building castles and palaces of extraordinary luxury with an eye for detail in the architecture, furnishings, and decor. He admired the splendor of France and lamented Bavaria’s architectural poverty. The exorbitant expense made him enemies inside the government. With the backing of Prince Leopold (Louis II’s uncle), some important ministers rebelled and conceived a plan to depose him for “psychiatric reasons,” among which they cited his aversion to administrative matters, his shy personality, the exuberance of his expenditures and his projects, his travels dedicated to learning about the architectural minutiae of other countries, and even such frivolous complaints as his preference for outdoor dining that would expose him to a risk of catching a cold. To what extent Louis II’s tormented homosexual orientation (well documented in his diaries) influenced the conspiracy against him is difficult to ascertain.2 It is not an unreasonable speculation though, considering the repressive culture that would give rise a few decades later to the psychoanalysis of Sigmund Freud.

The Monarch and the Medic

It is under these circumstances that the figure of Bernhard Von Gudden appears on the scene. He was head of the Munich Asylum and one of the instruments of the scientific revolution of neuropsychiatry in the nineteenth century.3 This transformation was based on the anatomical study of brain sections extracted during the autopsies of psychiatric patients. The systematic visual analysis of anatomical parts extracted after death allowed for a total reconceptualization of clinical language. This revolution led to the discovery of many neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and cerebrovascular disease, among others. In the genealogy of medicine, von Gudden himself was a scientific ancestor of Alois Alzheimer, who in turn discovered the disease that bears his name.1

Under political pressure, von Gudden and three other physicians wrote a legal report declaring that the King suffered “Paranoia.” In the strongbox at the Psychiatric Institute of the University of Munich, one can consult the evaluation, including a detailed list of extravagant behaviors. He was so afraid of coming into contact with other people that he had a small church built so that he could attend mass alone. When he attended the theater, no one else was allowed to attend. At palace luncheons and suppers he ordered large floral arrangements in order to hide behind them, and he insisted on music being played as loud as possible. He avoided contact with the most important members of his administration. On his daily strolls he would hear footsteps and voices that others could not make out; the palace would then have to be inspected so that His Majesty could be convinced that no one was there. In his chambers, the King would talk and laugh thunderously alone. His Majesty’s speeches would go on and on for three to four hours; he would use outlandish terms and could not manage to end the discourse. He would bow before a tree he considered sacred and hug a column of the Linderhoff Castle. For a whole year he ordered the valet Mayr to wear a mask whenever he had to approach him. If a footman mispronounced a foreign name, he could send him to jail. He would frequently punish the servants with whippings, to the point of drawing blood. In order to continue the construction of his castles, he sent emissaries to Brazil, Constantinople, and Tehran to ask for loans and when these were denied, he gave the order to rob the banks of Stuttgart, Berlin, Frankfurt, and Paris. The King’s sexual conduct was not included in the report.4

On June 10, 1886, the physician and a government convoy arrived at the King’s castle to ensure his imprisonment and dethronement. It is told that a baron loyal to the King confronted the committee with an umbrella. At the end of the day, Louis II had been declared unfit to govern. He was required to remain within the walls of the castle, while the King’s uncle, Prince Leopold, was proclaimed Prince Regent. Quite reasonably, Louis II asked Doctor von Gudden how he could have declared him mentally incompetent without ever having examined him. The doctor insisted that the facts spoke for themselves.4

The Castle and the Lake

The case of Louis II illustrates some ethical and legal problems that arise when politics meets psychiatry. On one hand, there is the criticism of the progressive (and excessive) medicalization of society. On the other we have medical professionals’ concern when they observe individuals in the upper echelons of executive power displaying symptoms of mental illness such as psychosis, addictions, affective disorders, or the syndrome of hubris, known from the ancient Greeks as a “drunkenness of power” that clouds one’s capacity for political discretion.

Are these purely theoretical questions? Currently, a group of psychiatrists have organized to impugn the mental health of the US president, despite a rule stated in the ethical principles of the American Psychiatric Association. The Goldwater Rule was informally named after the case of Senator Barry Goldwater, who ran against Lyndon B. Johnson for president in the 1964 elections: his defeat was accelerated by a newspaper article in which 1,189 psychiatrists stated that he was mentally incompetent to be president. The rule reminds professionals of the social responsibility implied in establishing a psychiatric diagnosis. The debate is far from over, and both sides bring persuasive arguments to the discussion. The consensus as of now dictates that a specialist must only give a formal diagnosis for patients under their personal care, in accordance with the best clinical practices.

The description of Louis II is highly suggestive of a disorder today called “delusional disorder” or even schizophrenia. Nevertheless, a physician must supplement indirect observations of the patient with direct observations obtained by means of interview and mental examination, given that third-person testimonials might indeed be biased by prejudices, political pressures, and other sources of error.2 This was not accomplished in the case of the Swan King, thus casting a shadow on the diagnostic accuracy. In most countries, there are no clear rules regarding when, how, and under what circumstances an objective clinical assessment should be mandatory for individuals in executive power.

The case of Louis II reveals the epistemological tension within psychiatry. Von Gudden was a leader in the field of neuropsychiatric anatomic pathology, which has generated objective and long-standing knowledge, such as the discovery of Alzheimer’s and other cerebral pathologies.1 However, such innovations in anatomic pathology were not useful for the diagnosis of Louis II, which was based exclusively on second-hand testimonies and the consensus of experts, with all the weight of cultural relativity that implies.2 Nevertheless, the story of the monarch, the musician, and the medic does not end with Louis II’s imprisonment.

Bernhard von Gudden remained in the castle. On June 13, 1886, at 6 pm, after expressing an optimistic opinion about the possible recovery of “his patient,” the doctor and Louis II went out for a walk without an escort to Lake Starnberg. They never returned. At 11 pm, both were found dead, drowned in the lake. The King’s watch had stopped at 6:54. The details of his journey to death are unknown. Was Louis II trying to escape and the doctor trying to impede his flight? Did they fight by the lake? Were they both murdered by conspirators? What is certain is that Louis II’s uncle, Leopold, governed as regent until his death. Leopold’s son inherited the post and eventually self-proclaimed himself King of Bavaria, with the name of Louis III.2

Irony has economic reverberations. Today the works of Louis II, irresponsible and eccentric as they were at the time, generate an enormous source of income for Bavaria, thanks to European cultural tourism. But I suspect Louis II would derive more pleasure from knowing that another extraordinary musician, Anton Bruckner, would years later dedicate his seventh symphony to the Swan King.

References

- Jesus Ramirez-Bermudez. Alzheimer’s Disease: critical notes on the history of a medical concept. Archives of Medical Research, no 43 (2011): 595-599.

- Heinz Häfner. The Bavarian royal drama of 1886 and the misuse of psychiatry: new results. History of Psychiatry, no 24 (2013): 274-291.

- Levent Sarikcioglu L. Johann Bernhard Aloys von Gudden: an outstanding scientist. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, no 78 (2007):195.

- Hector Perez-Rincon and Gerard Heinze, “El rey y su médico”, Salud Mental 9, no 4 (1986): 25-29

JESUS RAMIREZ-BERMUDEZ, MD, PhD, (Mexico, 1973) is head of neuropsychiatry at the National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery of Mexico. He has published many scientific papers in neurological and psychiatric peer-reviewed journals. He received Research Awards from the International Neuropsychiatric Association (Sydney, 2006) and the International Society for Bipolar Disorders (Pittsburgh, 2011). He is author of Paramnesia (novel, 2006) and the literary essays Brief clinical dictionary of the soul (2010) and A dictionary without words (2016). He won the National Literary Essay Prize in Mexico in 2009, with The Last Witness to Creation.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 10, Issue 2 – Spring 2018

Winter 2018 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply