Katherina Baranova

London, Canada

|

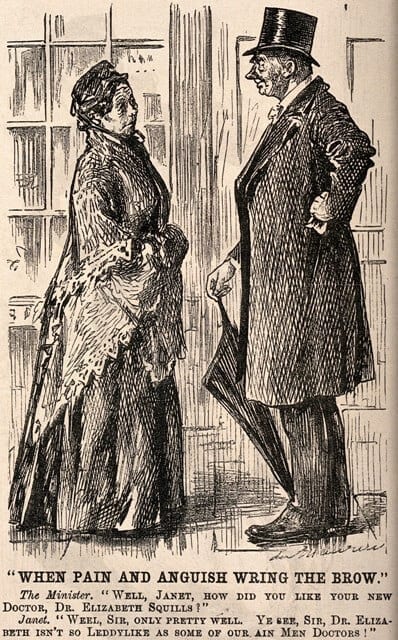

| A vicar asking a woman if she likes her new female doctor, the woman retorts that she prefers male doctors and finds them more gentle. Wood engraving after G. Du Maurier (1834–1896). |

The nineteenth century saw unprecedented changes in medicine, both technical and professional, as two parallel tales dealing with clubfoot demonstrate—Madame Bovary published in 1856 by Gustav Flaubert and “The Doctors of Hoyland” published by Arthur Conan Doyle in 1894.1,2 Both authors, though writing fiction, were well aware of the medical milieu of their time. Conan Doyle practiced medicine for years before attaining success as a writer. Flaubert’s father was the director and senior surgeon at a major hospital in France. In his novel, Charles Bovary’s clubfoot surgery on Hippolyte is a testament both to the state of medical ethics and to the horrors of surgery at the time. Hippolyte was essentially coerced into the experimental surgery, and not a week went by before his leg was discovered to have become gangrenous and septic. Monsieur Canivet, another doctor called to consult, scoffs at the attempted operation, saying “These are the inventions of Paris! … Straighten club-feet! As if one could straighten club-feet!” Hippolyte ends up requiring an amputation and his heart-rending cry is heard through the village.

In “The Doctors of Hoyland”, on the other hand, the operation to straighten a little boy’s club foot is dexterity itself. “[Dr. Verrinder Smith] handled the little wax-like foot so gently, and held the tiny tenotomy knife as an artist holds his pencil. One straight insertion, one snick of a tendon, and it was all over without a stain upon the white towel which lay beneath.” Even apart from the differences in the operation, Dr. Smith, unlike Charles Bovary, is intensely intelligent and competent, quickly making a mark on the people of the town with a firmness of manner and prodigal skill. She is also a woman.

Doyle thus offers a portrayal of a woman doctor who is not just equal to her male counterpart, but superior—feminine traits such as small hands even aid her in her work. This representation of women challenges the norm and expands the image of what a woman can do. Of course even in the story, the residing doctor, Dr. Ripley, is not particularly welcoming, and throws at Dr. Smith an insult common to an accomplished professional woman at that time. He refers to her as the “unsexed woman.” Becoming “unsexed” and unfit for feminine duties (namely childbearing and being a wife) was a major argument used against women entering higher education. In the 1865 article “Sex in Mind and in Education,” Henry Maudsley—a highly influential British psychiatrist—asserted that women were different in both body and mind, and would be put at risk of terrible ill-health were they to become doctors, or indeed receive any education similar to a man.3 He described the effects of being educated as ranging from nervous complaints, to psychological complaints, to some unseen regression of the reproductive system that would lead women to be unable to be good wives and mothers, and to fail to nurse. He wrote, “It certainly cannot be a true education which operates in any degree to unsex her.”

In Victorian England, the sex roles of men and women were sharply defined, and further enshrined in the newly emerging field of psychiatry. However, as social change progressed and women demanded equal rights and fair treatment, conflict arose between the male dominated medical profession that espoused these views and female doctors and female patients. Women began to speak and write openly about their views. In the academic sphere, the pioneering physician Elizabeth Garrett Anderson critiqued Maudsley’s views and his article.4 In literature, “The Yellow Wallpaper” criticizes the medical establishment’s treatment of women.5 In the short story, the young female narrator describes the course of her “rest-cure” for an unspecified nervous disorder. Throughout the story, the narrator makes requests—to leave the house, to change rooms, to be allowed to visit friends, to be allowed work or society—and is denied by her physician husband. She writes but is forced to hide it, as it may overexert her. She is allowed to do nothing and grows listless under the nothingness of her life.

In the end, the narrator evidently progresses into psychosis—with nothing to focus on and no stimulation, she begins to see patterns and a female figure in the yellow wallpaper. She ends the story circling the room, stepping over her husband as he lies on the floor in a faint. She declares, “I’ve got out at last in spite of you and Jane. And I’ve pulled off most of the paper, so you can’t put me back!” One way or another, the narrator has escaped the confinement imposed on her—mirroring the author’s own life, as Stetson was also put under a rest cure and felt she had nearly gone insane.

Literature thus offered a way to challenge social norms and bring social change to the forefront of popular culture. Many novels of the late nineteenth century likewise concerned themselves with the question of women doctors. In A Woman Hater, Dr. Harrington Vizard is moved by a sense of fair play to give a chance to the intelligent and charming Dr. Rhonda Gale.6 She is a mouthpiece in the book for medical and sanitary reform, as well as a character meant to garner sympathy for women as doctors. In the book, Dr. Gale rails against the image of women doctors as unsexed and astutely sets the argument in an economic context: “Nurses are not, as a class, unfeminine, yet all that is most appalling, disgusting, horrible, and unsexing in the art of healing is monopolized by them….No doctor objects to this on sentimental grounds; and why? Because the nurses get only a guinea a week, and not a guinea a flying visit: to women the loathsome part of medicine; to man the lucrative!” However, both Dr. Gale and Doyle’s Dr. Smith eschew marriage to pursue science and medicine.

Mona Maclean, Medical Student on the other hand, portrays the eponymous Mona having failed her medical school examinations and debating whether or not to become a doctor.7 When this book was written, the debate was not whether she could go to medical school—women had already been granted that privilege. This book instead asserts that women in fact can be doctors and find fulfillment and romance in their personal life. Rather than eschewing marriage, this book puts a professional woman squarely into the center of a classic Victorian romance plot. Mona is still limited in her practice—she ministers primarily to other women—but she was not “unsexed” and ends the novel married and working as a physician. Dr. Breen’s Practice gives a similar picture—with the close of the novel depicting the doctor married and continuing to practice medicine, something that was not deemed compatible in the Victorian era.8 Helen Brent, M.D. portrays Helen as a wise and reasonable person, unwilling to give up her practice for marriage, but ultimately loving and feminine.9

These portrayals of women moved beyond realism to argue a political point and to expand the narrow conceptions society held about women. Media depicts and shapes the image of doctors—and simultaneously sets up role models and ways of relating to medicine. In the nineteenth century, these books and stories offered representations that women could identify and live up to. In modernity, we can see this in media like the popular Internet campaign #ILookLikeASurgeon. Now and in history, literature depicts what exists and simultaneously contributes to the conversation and helps shape it, both reflecting and spurring social change.

References

- Flaubert, Gustave. Madame Bovary. France, 1856.

- Conan Doyle, Arthur. Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life. UK, 1894

- Maudsley, Henry. “Sex in Mind and Education.” Popular Science Monthly 5 (June 1874):198–215.

- Anderson, Elizabeth Garrett. “Sex in Mind and in Education: A Reply.” Fortnightly Review (1874) 38:582–94.

- Stetson, Charlotte Perkins. “The Yellow Wall-Paper. A Story.” The New England Magazine (1892) 11 (5):647–57.

- Reade, Charles. A Woman Hater. UK, 1876.

- Travers, Graham. Mona Maclean, Medical Student : A Novel. UK, 1892.

- Howells, William Dean. Dr. Breen’s Practice. USA, 1881.

- Meyer, Annie Nathan. Helen Brent, M. D.: A Social Study. USA, 1892.

KATHERINA BARANOVA, BSc, is a second year medical student at Western University in London, Canada. She is a co-president of The Osler Society at Western and has completed research projects in medical history as well as medical education. Her current interests in medical humanities are focused on portrayals of doctors in media and literature.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 10, Issue 2 – Spring 2018

Winter 2018 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply