Mahek Khwaja

Karachi, Pakistan

|

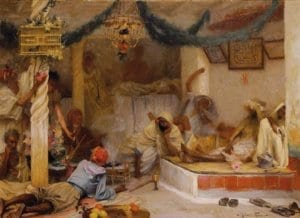

| Cannabis Shown as Eastern Antiquity. |

Analgesic potions containing herbs have long been prescribed to relieve pain and ameliorate suffering. Many such remedies contained alcohol and opium, such as Thomas Sydenham’s recipe of sherry wine, opium, saffron, cinnamon powder, and clove powder. Also widely used was cannabis sativa/cannabis indica, known as bhang, shahdanaj, qinnab, and kif in different parts of India, Arabia, and Persia. Hundreds of variations, including laudanum and black-drop (another preparation of opium and verjuice), used drug derivatives of cannabis, alcohol, mandrake, opium, and morphine.1

Wine and poppy had long been available in the West and were considered “gifts of God.” It was considered saintly to treat someone for his ailment.2 During the Crusades, as cultural and material trade increased, travelers to the Arab, Indic, and Persian world started bringing back accounts of how Arabs were not only aware of the intoxicating properties of these drugs but had also extracted their medicinal worth from classical texts. Travelers such as Rosenthal and Sacy reported the frequent consumption, especially of cannabis, by Persian and Iraqi sects located at the eastern periphery of the Islamic empire bordering the central steppes, where the cultivable plant hashish (botanical name for cannabis in Arabic) had its origin.3

The discovery of cannabis or hashish came as a scientific blessing to Western medicine, but also became associated with tales of indulgence in part of the Muslim world, notably among the Persian Nizari Ismailis of Alamut—who in some chronicles are called hashishyans (after the drug). The story of Hassan bin Sabah is quite famous, possibly weaving a fantasy or a metaphoric way to exhibit the chroniclers’ observations.

Hassan bin Sabah, in accordance with the decree of the Shi’i Nizari Ismaili Imam, founded the order of Persian Nizari Ismailis in Alamut, Persia in 1090. These later became known in the Black Legends as hashishyans by Venetian explorer Marco Polo, the French traveler Silvester de Sacy, and some Zaidi sources in Arabic from the Caspian region.4 As Gabriel G. Nahas puts it:

Hassan snared the young men and fed them a secret potion in the splendid gardens of his fortress, the Alamut. In this earthly paradise their main activity was to make love to sensuous women. This way Hassan kept his young followers under his spell and was able to send them on dangerous missions to assassinate his opponents. He promised the young men, “Upon your return, my angels shall bear you into paradise.”5

Sacy claimed that the secret potion was hashish, used to indoctrinate young fidais (loyal followers) who blindly followed his orders to assassinate his enemies. Sacy also stated that the term “assassins” was in fact a mispronunciation of hashishyans by the medieval European crusaders and became a part of the English lexicon meaning “a murderer.” Much violent behavior became associated with the hashishyans. Many Arab sultans and crusaders were murdered by them, including Conrad Marquis de Montferrat in whose camp an assassin penetrated, disguised as a monk. Even Saladin, the great Muslim warrior, at one time had to abandon his plan of assaulting Alamut.6

Now the question arises whether the consumption of a drug like cannabis could be a cause of violence of such magnitude? Let us look at its medicinal implications:

Cannabis was first used in China to relieve pain. Hua Tuo is the first recorded Chinese physician to have used the plant as an anesthetic during surgery. Medieval physicians in Europe, who had already used opium and morphine for pain management, welcomed this new ingredient.7 Cannabis had been used as a folk ingredient to induce sleep and to numb patients yelling with pain. Is it believable that Hassan could order the chronic use of such a drug among his soldiers, that would numb them and make them lazy instead of reinvigorating them?

Research published in the British Journal of Anaesthesia shows that the plant’s most potent psychoactive agent is tetrahydrocannibol (THC), which induces recreational illusions and is present in cannabis in greater concentrations than tobacco and other sedative chemicals. Its toxicity may not be a direct cause of death but there have been cases of coma following inadvertent consumption in children. The reason why it is largely used for pleasure is that small amounts can induce euphoria and loquaciousness. However, this euphoria may also be accompanied by a subsequent dysphoria, which generates restlessness, loss of control, crying, and fear of dying. This is true for almost all sedatives, making post-operative care difficult because as soon as the impact of anesthesia starts diminishing, patients experience unease and panic.

Physicians have noticed that compared to alcohol and benzodiazepenes the effect of cannabis may be more intense in producing sleep and drowsiness, leading to physical inertia, dysarthria, and general incordination.8 Hassan’s fidais on the other hand, were unusually alert during their activities, such as when they murdered Nizam ul Mulk, the Seljuk vizier, by gaining access in disguise and getting close enough to plunge their ceremonial daggers in his chest. Often the fidais would gain access to anti-Ismaili opponents by pretending to be excellent students in their private madrasahs. Even when they failed in their attempts, such as in case of Nur al Din of the Zengi dynasty in alliance with Syrian Crusades (under the leadership of Raymond III), their performance and strategy was remarkable.9 They were extremely shrewd, as depicted in their temporary friendship with the Knights Templar and the murder of Raymond of Antioch. None of their actions give a picture of a drugged and drowsy community that had no other work than giving in to sensuality.

The British Journal of Anaesthesia records that even small “social” doses of cannabis can impair performance in tasks demanding fine hand-eye coordination, divided attention tasks, and complex visual processing. Anesthetists today avoid using cannabinoids because of their slow elimination. The drugs may be present in the tissues of the patient for some weeks after last exposure.10 Dr. Farhad Daftary rightly claims that “addiction to a debilitating drug like hashish would have been rather detrimental to the success of faida’is who often had to wait patiently for long periods before finding a suitable opportunity to carry out their missions.”11

It is unclear whether cannabinoids increase appetite or decrease it, because there have been varying results in different cases. But it is agreed that cannabinoids, being antiandrogenic, decrease sperm count and motility in males, suppress ovulation in females, and cause a fall in sexual appetite.12 This would be in direct opposition to the erotic tales associated with the robustly sexual hashishyans who made love with hundreds of gratifying women in their paradisal gardens.

Dr. Daftary has concluded that the term hashishyan could quite sensibly be posed as a metaphor. Martyrdom and mindless obedience to an earthly leader would not have made sense to Orientalists who sought easy ways to rationalize things.13 The chronicles of Western travelers were marked by hyperbole, albeit the Persian Nizari Ismailis did observe some unusual practices pertaining to an esoteric faith and cannabis did grow in their habitat. Thus it is important to know that in so-called historical accounts, facts often fade under exaggeration but can be reevaluated when new scientific evidence comes to light, allowing them to be viewed through the mists of history.

References

- Gillian R. Hamilton, Thomas F. Baskett. “History of Anesthesia: In the arms of Morphine: the development of morphine for postoperative relief.” Canadian Journal of Anesthesia, 2000: 368.

- Mathew Zacharias. “The Worst of Evils: The Fight against Pain by Thomas Dormandy.” BMJ 333 (September 2006): 555.

- G. Nahas. “Hashish in Islam 9th to 18th Century.” Bull. N.Y. Acad. Med. 58, no. 9 (December 1982): 814-815.

- Farhad Daftary. The Assassin Legends. London: I.B Taurus & Co. Ltd, 1994: 90.

- G. Nahas. “Hashish in Islam 9th to 18th Century.” (See endnote 3): 815.

- , 815-816

- Lecia Bushak. A Brief History of Medical Cannabis: From Ancient Anesthesia to the Modern Dispensary. January 21, 2016. http://www.medicaldaily.com/brief-history-medical-cannabis-ancient-anesthesia-modern-dispensary-370344 (accessed January 10, 2017).

- H. Ashton “Adverse Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids.” British Journal of Anaesthesia 83, no. 4 (1999): 3.

- Mark S. Longo. Blood in the Sand: Shiite Assassins. January 22, 2016. http://warfarehistorynetwork.com/daily/military-history/blood-in-the-sand-shiite-assassins/ (accessed January 10, 2017).

- H. Ashton “Adverse Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids.” (See endnote 8): 4 and 8.

- Farhad Daftary. The Assassin Legends. (See endnote 4): 92.

- H. Ashton “Adverse Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids.” (See endnote 8): 8.

- Farhad Daftary. The Assassin Legends. (See endnote 4): 92.

MAHEK KHWAJA, MA, has completed her masters degree in English Literature and currently works as an editorial assistant at the Medical Division of Paramount Books Ltd, a leading publication house in Karachi, Pakistan. She previously served as an intern at Aga Khan University and Hospital, Karachi at Jivraj Library for the linguistic revision of medical periodicals. With her expertise in humanities and work exposure at medical academics, she is particularly interested in tracing confluence between history, literature, and medical science.

Winter 2018 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply