Maureen Miller

NY, United States

|

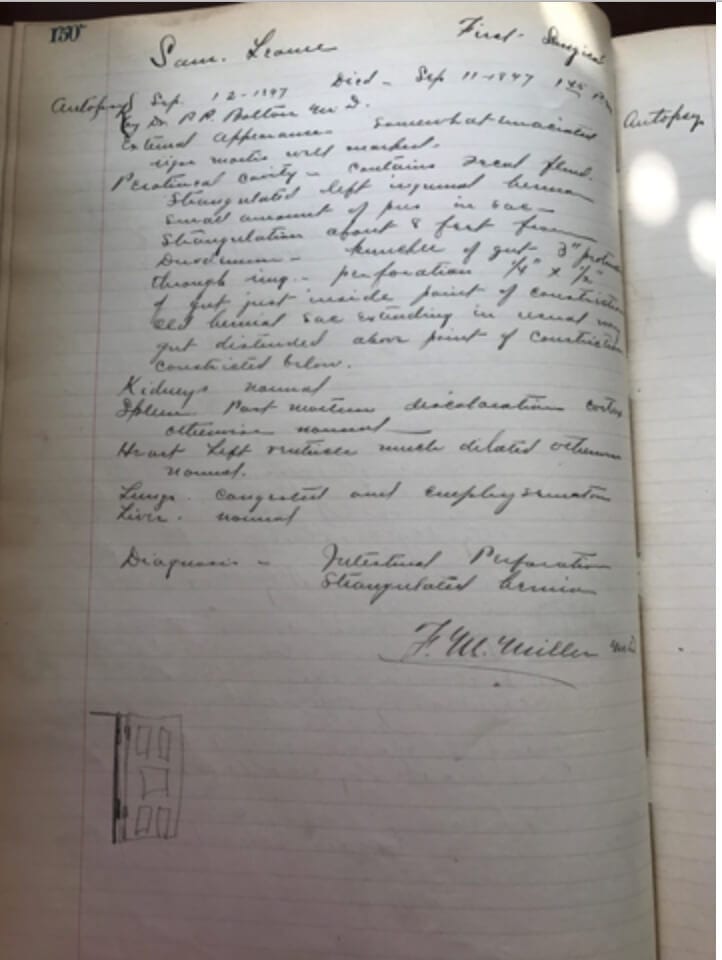

| A September 12, 1897 autopsy report diagnosed a surgical patient with an intestinal perforation. Below the note, an unknown active reader sketched a door. Medical records, 1897, property of Bellevue Hospital Department of Pathology, New York, NY. Photograph by Maureen Miller, September 2017. |

The post-mortem room should be supplied with a small mirror, so that

the operator may satisfy himself that no evidences of the character of his

work are left upon him before appearing in public.

– T.N. Kelynack, The Pathologist’s Handbook: Manual for the Post-Mortem Room, 18991

On January 1, 1898, New York City consolidated the five boroughs. The Consolidation Act bulked up public infrastructure. It also reorganized the coroner system just as local physicians noted a striking decline in mortality from infectious diseases.2 In 1897, about seven hundred people in the city died each week. That number spiked in July and bottomed in November.3 Pneumonia, tuberculosis, diarrhea, and enteritis were primary culprits.4 With breastfeeding, infant mortality dropped from near certainty to 30 percent.5 That achievement is often credited to Bellevue Hospital public health worker Stephen Smith, the first physician appointed to the Board of Charities, but a talented class of Bellevue pathologists also contributed to changing the death toll.

The Bellevue Department of Pathology has rediscovered volumes of water-damaged, longhand notes in storage that document examinations of hundreds of cadavers by the hospital at the turn of the twentieth century.i Local anatomy instructors had welcomed the 1854 Bone Bill, which facilitated cadaver procurement for medical education in New York State, but these recovered records documented routine autopsies by the country’s best researchers.

The city’s first chair of pathology, William Welch, left Bellevue in 1885 to found Johns Hopkins, right as Andrew Carnegie endowed an experimental laboratory for antisepsis expert Frederick Dennis.7,8 The lab survived a January 1897 fire that ravaged a neighboring building with an expired lease. Fire damages ran to tens of thousands of dollars, including specimens.9 No evidence suggests record destruction, but no reports from early 1897 are archived.

Surviving documents describe pathology education at Bellevue Hospital Medical College. Students paid forty dollars for seasonal lectures and laboratory practicals. A five-dollar matriculation ticket let them in, and then they put forward ten more dollars for daily dissection demonstrations. There were courses in urine examination, microscopy, and bacteriology. Surgical pathology was an extra forty dollars, plus two to make histology study sets.10 The 133 graduates of the Class of 1897 were male. Most were Northeasterners. The student body had seven students from the West Coast and twenty-five from abroad, including the Caribbean, Canada, South America, northern Europe, Italy, Russia, and Syria. The top four graduates each received $100; the valedictorian and salutatorian were awarded a Bellevue residency.11

Chief complaints have a character limit, but there was no limit to the characters Bellevue residents encountered. Each time a patient took asylum, the New York Times was on it. An orderly “believ[ed] he was the finest Police Sergeant in NY.” A confabulating Franco-Prussian War veteran “would, in growing more earnest, break into voluble German.” A young professional was “insane from worry over promotion.” A house servant was stabbed by her corset. This or that person was “impaled by buggy shaft.” A widow swallowed a pin. A catatonic mystic lost himself. The Bronx’s coroner stroked out. A man “wished to reveal the whereabouts of valuable gold mines.” A professor was unlawfully detained for self-treating consumption with a daily quart of ice cream followed by stomach pump. “I haven’t eaten anything but human flesh for months, and I need a good feed to start on,” a cannibal said. Better to be a spinster “suffering from a sprained ankle from slipping on a banana peel on the pavement.” Twenty-five years before, “her name was known the length and breadth of Europe.”12 Most died like her, unknown.

Between March 16 and December 31, 1897, Bellevue reported results from 324 autopsies on nobodies.ii The records do not list the treating clinicians, though almost all the signing pathologists were also in clinical practice. The combined medical divisions—Columbia, Cornell, Bellevue and NYU—ordered at least 208 autopsies, the surgical services twenty-one. Average turnaround time was forty-three hours after death. Thirty-nine were done on the same day, others two weeks later. Today, pathologists may wait a week for clearance, file a preliminary diagnosis within forty-eight hours, and finalize in ninety days.

The decedents included 222 men and 82 women. The adults’ average age at death was 42 (range 19-78 years), and 17 months for children (as young as 3 days old, one age 13), compared to a national life expectancy of 46 for men and 48 for women. Six decedents were identified as “colored.” Eleven were from western Europe. Two decedents were referred from the insane pavilion, one from the emergency ward, and one from prison. Six were found on the street.

The most frequent cause of death was tuberculosis (116 decedents). Eighty-eight patients had nephritis (Bright’s disease). Sixty-nine died of pneumonia, thirty-one non-tuberculous meningitis, thirty of cardiovascular disease. Fourteen were said to be cirrhotic, twelve others with fatty liver. Ten with similar physical findings were diagnosed with alcoholism. About a dozen decedents had peritonitis, pleurisy, or apoplexy. Ten were malnourished. A few had enteritis, septicemia, or non-cerebral thromboembolic disease. One decedent’s gummatous lesions were compatible with syphilis. Three had typhoid fever, two diphtheria, one malaria. The typhoid fever patients preceded Mary Mallon’s cluster by three years.

Not all the deaths were natural. Two had antemortem psychoses; one died in a manic episode. Four died of poisoning, by carbolic acid and Paris Green paint. Four asphyxiated. Six died from trauma. Three had wound infections. Nineteen had neoplasms, mostly gastrointestinal carcinomas, but also brain tumors, ovarian masses, and a sarcoma. These diagnoses were on good faith.

Bellevue physicians did their best to master death. Their practices defined best practices. The ABC’s of autopsy in the 1890s were antisepsis, body identification, consent by next-of-kin, corpse preservation, dictation to two or more pathologists in attendance, fast moves, natural lighting, and personal protection (rubber gloves, forearms in beeswax).13 Autopsists were senior lecturers, laboratorians, and medical and surgical trainees. They were not interesting on paper. Outside it, they were polymaths.

Star intern Joseph Goldberger took a hardscrabble childhood in a Hungarian section of the Lower East Side to a pellagra cure and the measles vaccine. Horace Bigelow, likely most senior, and whose name appeared on most reports, was a “club man of New York.” E.L. Dow developed a classification system that anticipated ICD coding. H.H. Brooks wrote against bedside manner. Charles Slade wrote a physical examination textbook. G.H. Fox pioneered medical photography. P.S. Boynton climbed mountains between anatomy demonstrations. Pediatrician Abraham Jacobi was convicted of treason. George Bolling Lee, grandson of Robert E., did gynecologic surgery. A Dr. Norris may be Charles, the founder of modern forensics. He returned to New York in the late 1890s from training in Europe. Either way, coroner Philip O’Hanlon was on the books. His daughter, Virginia, investigated the existence of Santa Claus.

Their prose was functional, and purplish in spots. They wrote of “a small sac the size of a butter nut;” “a stone the size of a hazelnut;” “cyst with friable glassy contents size chestnut;” “two calculi about size of English walnuts;” a coconut (sic) uterine fibroid. Some wrote of duck and pigeon’s eggs, small and large hen’s eggs, eggs from robbins (sic). Their reference points were not all avian. Birdshot came from ballistics.

One report was the size of a rabbit hole. Fred Albers, age forty-five, had good general nutrition and “small purplish spots over extremities.” His liver was small, two pounds and nine ounces, with a smooth capsule and “somewhat congested” firm parenchyma. Albers’s intestines showed “contracted mucous membranes, seared, cracked and contents give off strong odor of carbolic acid; entire lines of esophagus seared and white.” The New York Times was more caustic:

MRS. ALBERS’S WISH GRANTED.

While Praying that Her Drunken Husband Might Die He Expired in Bellevue Hospital.

Death filled two east side homes with joy and sorrow yesterday. Joy was in one where a father’s angry voice would never be heard more; sorrow in the other where an aged woman was weeping for her son. The dead man was Frederick Albers—a drunkard and a vagabond. His wife and children, the oldest a boy of seventeen, live at 505 East Eighteenth Street.

Mrs. Albers had one of the tidiest homes in all that neighborhood. Her children are well clothed and fed and go to school. But whenever the father’s step was heard upon the stairs, the children ran away in fear and the mother nerved herself with grim despair to meet the man who called her wife. Blows and abuse were hers when he was home, and it had been so she says for eighteen years, save only during the intervals when Albers was in jail.

Mrs. Albers on Friday night heard that her husband had been picked up on the street and taken to Bellevue Hospital. She prayed that he might die. She asked her Maker to forgive his sins, and take him from this world. Her prayer was answered. Albers died, and Mrs. Albers gathered her children about her on their knees and thanked God that He had heard her supplication.

Mrs. Albers is to get $200 insurance on her husband’s life. She intended to let the city bury him, but said yesterday she had changed her mind when she thought of her children.14

The Pulitzer Prize was not awarded for another twenty years, but this unbylined potboiler rivals Nellie Bly and Joseph Pulitzer’s 1887 foray into Bellevue psychiatry in local color.

That was as colorful as it got, unless one counts the rust-colored disintegrating spine. The handwriting was overwhelming, the paper brittle. Ink bled, blurring appropriately bloodless notes. Dead teach the living, mortui vivos docent, and they leave a trainee at the American Board of Pathology ceiling of fifty procedures feeling pretty humbled.

Notes

- The research the author describes in this essay is used in a poster presentation of the same title, to be given by the author on March 20, 2018 at USCAP 2018, Vancouver, BC. This essay expands significantly on that and is the first related print submission. Both projects summarize findings from a May-September 2017 retrospective medical record review of several volumes of autopsy reports (ca. 1897-1906) from Bellevue Hospital, New York, NY. The books are archived in the Bellevue Department of Pathology. The full text of each report (n=324, excluding one duplicate entry and inclusive of all autopsy reports found from the year 1897, here March 16-December 31, 1897) was transcribed by the author and collated into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Each decedent’s name, age, race, ethnicity, country of origin, medical division, ward assignment, time of death, time of autopsy, and autopsist(s) were recorded, along with external examination findings, gross findings by organ system, and final anatomic diagnosis. Autopsists reported multiple final diagnoses. The report texts were reviewed, and descriptive statistics were compiled (e.g. cohort demographics). There was no re-classification to modern autopsy report conventions, save measurement conversions to metric system dimensions.

- The name of each decedent in the autopsy reports was cross-referenced with free online death records (e.g. New York State Death Index), contemporaneous New York Times archives (January 1, 1896-December 31, 1898), and hospital photographs and documents archived online by the Lillian and Clarence de la Chappelle Medical Archives at NYU Health Sciences Library, Museum of the City of New York, New York Public Library, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

References

- Kelynack T.N. The Pathologist’s Handbook: Manual for the Post-Mortem Room, Chapter II: General Considerations, 6-12. London: J. & A. Churchill, 1899. Via National Library of Medicine.

- Wikipedia, History of New York City.

- Oshinsky D. Bellevue: Three Centuries of Medicine and Mayhem at America’s Most Storied Hospital. New York, Doubleday.

- Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol. CXXXVI, 1897. Via Google Books.

- CDC MMWR July 30 1999 48 (29);621-629.

- See Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol. CXXXVI, 1897. [4]

- Prose F. “The Old Morgue” Threepenny Review No. 71 (Autumn, 1997), pp. 16-18. Via JSTOR.

- “History of the NYU SoM Department of Pathology,” https://med.nyu.edu/pathology/about

- See Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol. CXXXVI, no. 4 (20 Jan 1897). [4]

- “Bellevue Hospital Medical College and Carnegie Laboratory Spring Session 1897.” Lillian and Clarence de la Chappelle Medical Archives, NYU Health Sciences Libraries. PDF: https://archives.med.nyu.edu/islandora/object/nyumed%3A1281/datastream/OBJ/view

- “Bellevue Hospital Medical College Commencement, 1897.” Lillian and Clarence de la Chappelle Medical Archives, NYU Health Sciences Libraries. PDF:https://archives.med.nyu.edu/islandora/object/nyumed%3A1157/datastream/OBJ/view

- New York Times archives, search “Bellevue,” January 1, 1896-December 31, 1898.

- See Kelynack T.N. [1].

- New York Times, April 9, 1897. “MRS. ALBERS’S WISH GRANTED.”

MAUREEN MILLER, MD, MPH, is a resident in anatomic and clinical pathology at NYU Langone Health. In summer 2018, she begins a fellowship in transfusion medicine at Emory School of Medicine. You can read more of her writing at doctorwritermaureenmiller.tumblr.com.

Acknowledgements: The author would like to acknowledge Drs. Jonathan Melamed and Amy Rapkiewicz and Gerald Davydov, PA from the Bellevue Medical Center Department of Pathology, New York, NY for their assistance in this archival work.

Winter 2018 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply