Sarah Wise

London, United Kingdom

“My mind had been running on Grace Poole — that living enigma, that mystery of mysteries,” Jane Eyre admits to herself, one evening at Thornfield Hall. Charlotte Bronte’s readers’ minds also run on Grace Poole throughout the Thornfield chapters of the novel — from the first “mirthless” laugh that housekeeper Mrs. Fairfax attributes to Grace, through to the revelation of Grace’s true identity on what was to have been Jane’s wedding day.

For those who after finishing Jane Eyre care to pick away at some of its narrative threads, Grace remains the largest enigma in the tale; and we may, if feeling churlish, suspect that in her conception and execution of Grace Poole, Bronte pushed too hard at the boundaries of probability. After all, she expected her readership to believe that Grace would willingly endure the best part of a decade locked for twenty-three hours out of twenty-four in a windowless room with the seriously intellectually disturbed Bertha Rochester. In Jane Eyre, published in 1847, Bronte introduced into fiction the figure of the nurse-attendant to a “lunatic,” although we do not understand Grace Poole’s real job and its significance until after the novel’s catastrophe. Grace, however, remains a puzzle, despite Bronte’s eventual revelation of her true role within Thornfield.

Grace is a creature of porter, pipes, pudding, cheese, sago, and slippers. Jane describes Grace as square in shape, red-haired, matronly: “hard-featured and staid, she had no point to which interest could attach.” Jane, in an attempt to amuse herself and to calm her anxieties about Grace, posits her as a Gothic character — as a “pale” and “desperate” murderess, as such were configured in the hugely popular Gothic fiction of the day. On the morning after the mysterious fire in Mr. Rochester’s bedroom, Jane interrogates Grace; but the latter’s hand remains infuriatingly steady as she threads her needle to sew, and she retains what Jane describes as “miraculous self-possession.”

Oxford academic Sally Shuttleworth has demonstrated Bronte’s knowledge of James Cowles Prichard’s (1786-1848) theory of “moral insanity” (popularized in Britain from the mid-1830s).1 Shuttleworth relates this knowledge to Bertha’s condition;2 but I would argue, further, that Jane’s eager attempts to analyze Grace are also inflected by contemporary ideas about moral insanity and “monomania.” Perhaps the most sinister aspect of the moral insanity concept, for lay people, was its revelation that murderous lunacy could lurk within the most rational-seeming of individuals. During their post-arson exchange, Grace’s replies to Jane’s questioning show her speech to be precise, grammatically correct, slang-free and gossip-free. This is not the speech of even a higher servant, such as Mrs. Fairfax. Like her unreadable face, Grace’s speech offers Jane no clues.

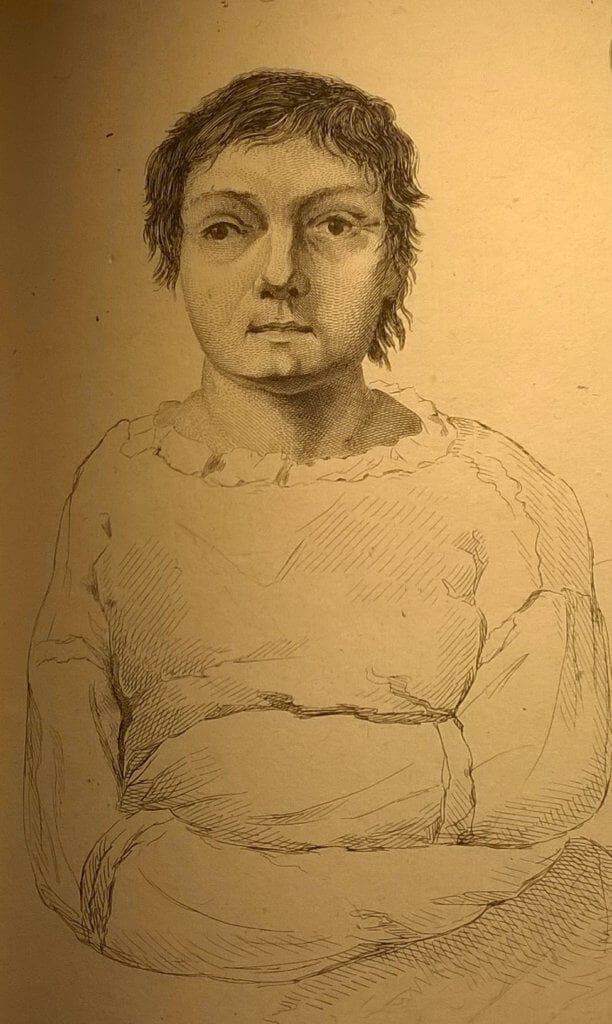

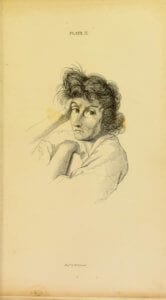

Experts sought to reassure the public (and themselves) that most forms of insanity could be diagnosed by facial profiling. The first English professional journal of psychiatry (or “alienism”) began publication the year after Jane Eyre was published.3 In this magazine, and its later rivals, sketches (and, later, photographs) were occasionally printed to “reveal” how physiognomy and facial expressions were linked to certain psychiatric diagnostic categories. [See illustrations.]

The majority of Bronte’s readers will have been aware of both the notion of “hidden madness” plus the doctors’ attempts to discern insanity within the human face; and thus they would have understood the added urgency of Jane’s quest to de-code Grace.

Grace, as an attendant to a “lunatic,” is the physical embodiment of a restraint — a lock; a block on movement; a barrier to freedom. Not for nothing is Grace’s longest dialogue delivered as she is sewing heavy brass curtain rings, like manacles, on to Mr. Rochester’s fire-damaged four-poster-bed curtains. Of course, it turns out that Grace is not a good restraint, and it is her porousness in this role (her resort to gin to free her temporarily from the boredom and tension of her own restricted life) that leads to the ultimate disaster.

Bronte’s novel is packed with barriers — window panes, doors, heavy curtains, thick stone walls — with Jane placed on one side, yearning for the freedom to witness what may be beyond, on the other side. The contrasting of interiors and exteriors, of vast tracts of bleak space with minuscule places of confinement, repeat throughout Jane Eyre. Grace, with Bertha, inhabits the tiniest, closest seclusion. Jane’s great internal monologue about women’s freedom takes place in a corridor on the other side of the wall from Bertha, who lives in solitude and stagnation, trapped in her own prison of a malfunctioning intellect, along with Grace, who shares Bertha’s “goblin cell.”

Plate 10 (X), in same: ‘Monomania With Depression a female laboring under partial insanity with depression, or, as it has been termed by Dr Esquirol, Lypemania.’ From the Wellcome Collection

From the Wellcome Collection

Charlotte Bronte and her original readers knew that in keeping his mentally ill wife confined without a certificate of lunacy, Mr. Rochester had broken no law. A spouse, a blood relative, and even an in-law were legally permitted to keep an insane family member confined within the home, provided that they were indeed mentally ill, and additionally that no cruelty was used during the detention. The ethics of this behavior are less certain, though, and not just to 21st-century readers. Bronte kept well abreast of current affairs, and will have known of the upheavals in English lunacy care that marked the mid-1840s. The Bronte family’s own difficulties — with the only son, Branwell, stalking the household by night, sometimes armed with a gun, as his own breakdown worsened — may have further piqued Charlotte’s interest in the subject. A government report of 1844,4 which caused a stir in the newspapers of the day, established that many families were struggling to care for their mentally ill relative at home, fearful of bringing them forward to the English state asylum system and unable or unwilling to pay for a private asylum placement. A number of well-publicized scandals had proven, after all, that even in the most exclusive private asylum a patient could be subjected to the straitjacket, cold-water shock treatment, solitary confinement, and so on, even though the use of these were banned by the governmental inspectorate, the Commissioners in Lunacy. The Commissioners’ revelations in the mid-1840s of relatives hidden away in sheds, attics, and remote chambers created a shudder for anyone who read them, even when it was clear that the family was acting in what it believed to be the sufferer’s best interest.

Thornfield Hall’s third-story “secret inner cabinet” was Mr. Rochester’s solution to his predicament. And so that she would have permanent, personal care, he hired Grace Poole from the Grimsby Retreat, where her son was superintendent — “Retreat” indicating an advanced, humanitarian, Quaker-inspired institution, where physical restraint was minimal. Bronte’s original readers will have known that she was signaling with the use of the word “Retreat” that Mr. Rochester was carefully choosing from the best of a range of bad options.

A number of “retreats” existed in Britain — lunatic asylums rebranded, often rather cynically, to capture the allure of the original, the York Retreat, famous throughout the English-speaking world for its humanitarianism. Quaker Samuel Tuke had opened his small charity-funded asylum in York in 1796 in reaction to the infamous cruelty at the public York Asylum. In line with Quaker thinking, manacles and other mechanical barbarities were dispensed with in favor of “moral treatment,” by which those patients who were deemed to be curable were encouraged to develop their own “self-government” through conversation and sympathetic listening; the apparently incurable were also to be treated with kindness and compassion.

Tuke recruited Katherine Jepson as his first matron, and in true Quaker style he permitted this female worker as much authority and autonomy as if she had been a male attendant.5 Described by former patients as warm, compassionate, and smartly dressed, Mrs. Jepson is clearly not Grace Poole; but the idea of a female Quaker authority figure who is expert and capable may have been an influence in the characterization of Grace. Notably, in the attic scene, in which are present a vicar, a lawyer, and the master of the house, the true authority figure is, in fact, Grace Poole.

Despite the wry admission by Jane that she cannot easily project Grace into a Gothic mode, Grace nevertheless does exist in that very mode in Jane’s mind — and in our mind, too, even after we have closed the book, with her true identity “solved.” When Grace’s literal, mundane self is revealed in the attic scene, the two personae are not skillfully resolved by Bronte — the Gothic, and the social-realistic. The two images of Grace do not need to be harmonized, of course, in terms of the raw plotting. However, perhaps this is why Jean Rhys battled unsuccessfully in her attempt to ventriloquize Grace, in Part 3 of her 1966 novel Wide Sargasso Sea (Rhys’s rewriting of Jane Eyre from Bertha Rochester’s point of view). Rhys had intended to write the final section entirely in Grace’s voice but abandoned this, admitting: “Mrs Poole will talk wrongly however I do it.”6

Perhaps Rhys’s failure lay in the sense that the real Grace strains credulity, where the phantom Grace (the inscrutable source of domestic malevolence) does not. Fact seems significantly less likely than fantasy in the case of the mysterious Grace Poole.

Notes

- Prichard, James Cowles. A Treatise on Insanity and Other Disorders Affecting the Mind. London, 1835

- Shuttleworth, Sally. Charlotte Bronte and Victorian Psychology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1996

- The Journal of Psychological Medicine and Mental Pathology was launched in 1848

- Supplemental Report of the Metropolitan Commissioners in Lunacy to the Lord Chancellor, Relating to General Conditions of the Insane. London, 1844

- Digby, Anne. Madness, Morality and Medicine: A Study of the York Retreat, 1796-1914. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1985

- Rhys, Jean. Letters, 1931-1966. Penguin, London, 1984. Letter dated August 16, 1963

SARAH WISE, MA, has a master’s degree in Victorian Studies from Birkbeck College, University of London. She teaches in the English Department of City University, London; and lectures in 19th century social history at the University of California’s London Study Center. She is the author of The Italian Boy: Murder and Grave Robbery in 1830s London (2004), shortlisted for the Samuel Johnson Prize and winner of the Crime Writers’ Association Gold Dagger for Non-Fiction. The Blackest Streets (2008) was shortlisted for the Ondaatje Prize and was a Radio 4 Book of the Year. Her most recent book, Inconvenient People, was shortlisted for the 2014 Wellcome Trust Book Prize.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 10, Issue 2 – Spring 2018

Leave a Reply