Catherine Lanser

Madison, Wisconsin, United States

My headaches started after my first period when I was a freshman in high school. They were dull, daily, aching headaches that were manageable. I usually just took some acetaminophen and they went away. But none had been as bad as the one gripping me on one memorable day. I felt as if someone had put my head in a vise. I took more acetaminophen; After lingering a few long days it disappeared.

The daily headaches felt like almost nothing compared to this new siege in my cranium, which kept returning when I least expected it. To manage this new headache, I would take as many acetaminophen as I could every four to six hours, even if it was pointless against the pain.

I was in my twenties before a doctor used the term migraine to describe my headaches to me. Now, after dealing with migraines for most of my life, I know a lot more, but I am still learning. Medical professionals continue to learn too.

|

|

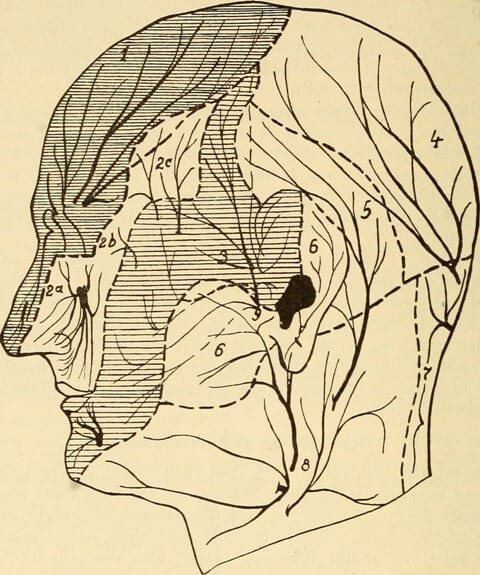

Fig. 189 – Diagram showing the distribution of the sensory cutaneous |

For a long time, doctors assumed that migraines started when blood vessels in the brain expanded. Now the thinking is that migraines start when a wave of electrical energy spreads across the brain. The charge hops from cell to cell, leaving the brain imbalanced and unstable. This finally sets off a sensory nerve on the side of the face, called the trigeminal nerve. This is the point at which the blood vessels in the brain, the ones that have always been associated with migraine, dilate.1

Though researchers are beginning to understand this new process, they are still trying to figure out what causes the electrical storm in the first place. Some say that migraine sufferers just have hypersensitive brains. When someone prone to these attacks encounters something that upsets their brain, it sets off the reaction. I have many guesses about what causes my migraines — an uptick in estrogen, a change in the barometric pressure, nitrates from ham, a sleepless night, or a lot of other things I have not figured out yet.

I do not know how long the brain is under siege before the pain starts. I think it must be a long time, because my migraines start slowly, slipping in quietly, hiding in the corners of my skull, without pain, for at least a day or so.

The first inkling I get is an itch. It spreads across my face and into my nose until I am batting at the tip back and forth and in circles, but never able to reach a source of relief. Sometimes instead of an itch, I yawn and yawn, opening my mouth wider and wider as if I cannot get enough air, though I am not exactly sleepy. Medically this is known as a prodrome, an early warning sign that that the migraine is squatting in wait. It should be a warning sign of what is about to come, but it is hard to know if I am just itchy or tired or if I am indeed on my way to a migraine. Even after a lifetime of migraines I never know which strange hints will lead to a full-on attack.

The day after a prodrome, things start happening more quickly. I might have an aura of flashing lights or a sort of blindness that looks to me as if there is a bright beam of light somehow shining from inside my right eye. If I have one, and again, if I recognize it, I am lucky, because this is the clearest sign that a migraine is about to render me useless.

If I have not taken any migraine medicine, the pain begins slowly. First, there is a slight flick of a finger inside my skull. If I have missed all the previous hints, I might take an ibuprofen, but only if I am still enough to feel that little twitch in my head or maybe in the area that does not seem to belong to my skull or face behind my cheekbone and temple. After a little bit the flick becomes more persistent, knocking more frequently until it is not just the tip of the finger tap, tap, tapping, but the whole hand. Then the hand becomes a fist and the fist becomes a hammer.

Then a brush is dipped in red paint that has the intensity of oil paint but spreads like watercolor. The paint brush finds the deepest fold of the brain and touches down, swirling the pain throughout the creases, turning grey matter red hot with a spasm of agony.

“Ha, ha, ha,” a voice laughs. “It wasn’t just a headache.”

Then I know I have just wasted six hours because I cannot find relief with my prescription migraine pill until the ibuprofen wears off. I wonder if I can still take a migraine pill and how much damage I have done to my liver. I think about how many pills of ibuprofen I have taken in my life. And how many acetaminophen before that. I wonder how many days it will be until the red washes out of my brain.

I raise my hand to my head, grabbing under my eyebrow and wishing I could pull off the part of my skull where I feel this pain. I move slowly, so the upper right front quadrant of my brain, where the pain resides, stays still. It feels as if it has dislodged from the rest of my head and my brain is jostling around inside. I want to cleave off this part of my head and throw it on the floor. I dig my thumb deep into my temple. It feels good to press hard, but my head is sensitive to the touch, as if the brain, which does not feel pain, is oozing out.

The pain continues for two, or perhaps three days. Sometimes during that time, I will think the migraine has left me, but then when I move my head I notice my brain shifting inside my head again, banging into my skull. Finally, when I am so wiped out I do not think I can take another moment, I realize the migraine is gone.

When I was a freshman in high school I only knew that pills had been invented to cure headaches, just like casts were invented to heal broken bone. Now, after a lifetime of migraines, I know that progress in this area is slow, but like the researchers rediscovering these strange headaches, I am discovering my own migraines again and again. Each time I learn a little more. Each time, finding more relief.

References

- Carolyn Bernstein and Elaine McArdle, The migraine brain : your breakthrough guide to fewer headaches, better health (New York : Free Press, 2008), 43.

CATHERINE LANSER, is a writer from Madison, Wisconsin. She writes essays and narrative nonfiction about her life in the Midwest and growing up as the baby of a family of nine children. This piece is an excerpt from her forthcoming memoir, In the Absence: A Memoir of the Brain.

Leave a Reply