Joseph deBettencourt

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

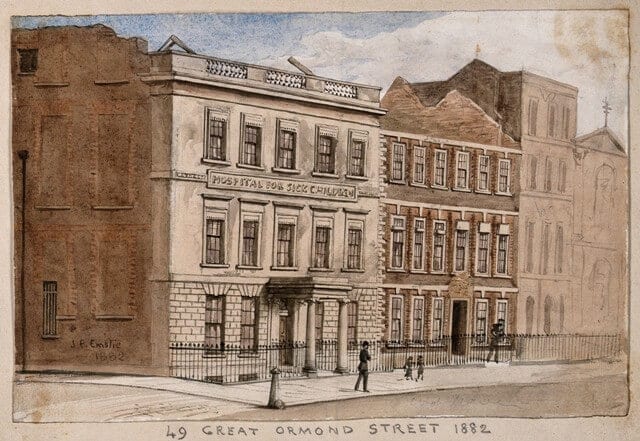

| An artist’s rendering of the original Great Ormond Street Hospital building in 1882, before it was demolished. “49 Great Ormond Street, London, in course of demolition.” J.P. Emslie, 1882, Wellcome Collection, UK Wellcome Collection. |

Down a narrow street in an old London neighborhood sat a large, forgotten house. It used to belong to a well-known doctor who built an addition just for his medical library, inviting students to come and pour over the leather bound tomes he spent his life acquiring. With the windows open during a warm day, the students would have been able to hear the sounds of children practicing choral pieces at the nearby orphanage. Handel was the children’s favorite composer, and the orphans knew his pieces by heart.

On this particular day, the windows of the old house were shut tight against the cool February weather. There were no students studying, the books and specimens had all been removed to a smaller room in the house, and the library was converted into a make-shift reception area. Upstairs, the normal furniture had all been removed and a series of small beds had been neatly arranged along the length of the room. Instead of housekeepers, nurses worked quietly to arrange the linens on these tiny cots and organize supplies. Downstairs, a doctor was waiting to open the doors for the first time to England’s first pediatric hospital: The London Hospital for Sick Children, located at No. 49, Great Ormond Street.

Dr. Charles West had studied in Europe and had seen firsthand the strides being made to care for the children of the working poor. Upon returning home, he was determined to bring England up to the same standards he had witnessed elsewhere. If he expected open arms and an outpouring of support, he had not received it. Despite the constant presence of sick and dying children on the streets of London, many in the medical field were unmoved. “The causes of the enormous child mortality are perfectly well known . . . in one word, defective household hygiene. The remedies are just as well known; and among them is certainly not the establishment of a child’s hospital,” wrote Florence Nightingale in her book Notes on Nursing.1 English society, it seemed, was more than willing to blame the parents of these unfortunate children. Parents, for their part, were unsure about bringing their children to a hospital away from their homes. Their fears were well-founded; the orphaned children singing Handel across the park had only a thirty percent chance of growing into adulthood.2 Indeed, the hospital’s beds remained largely empty the first month of operation; eight patients were admitted and only twenty-four came to the hospital for consideration.3

As Dr. West examined Eliza, a squirming small girl of three-and-a-half,4 a home just up the street was humming with productivity. Having just published The Old Curiosity Shop following Nicholas Nickleby, Charles Dickens was already well known in literary and philanthropic circles. He had turned forty just a week prior to the opening of Great Ormond Street. Those forty years had brought him fame and fortune but, like many of his characters, his past was always part of him. Charles would always remember how he spent the week after his twelfth birthday in a rat-infested factory, pasting labels on bottles of boot blacking.5 While he had been born into a reasonably comfortable life, things soon became very difficult for his family. His father ended up in jail and before the age of ten, he had seen two of his siblings fall ill and die. Since achieving notoriety, he made it a point to speak publicly and in his writing about the plight of England’s poor. Through mutual friends, he had come to know about the small hospital a mere twelve minutes’ walk from his home. Despite the doubting words of others in the medical field, Charles Dickens knew too well the need that existed in London’s streets. Dickens picked up his pen and wrote an impassioned cry to his readers in England.

No hospital for sick children! Does the public know what is implied in this? Those little graves two or three feet long, which are so plentiful in our churchyards and our cemeteries to which, from home, in absence from the pleasures of society, the thoughts of many a young mother sadly wander, does the public know that we dig too many of them?6

Dickens published the piece in his weekly periodical Household Words, with the co-authorship of Henry Morley, a writer and physician. While the latter half of the piece is often credited to Morley, the lines quoted above are Dickens’.

Dr. West had struggled unsuccessfully for years to open the London Hospital for Sick Children, and now he had done it. His only issue was that he had yet to convince the public and many of his peers that it should exist. The final step in operationalizing England’s first pediatric hospital was a step into the hearts and minds of everyday people made by an artist and author, not a physician. The impact of this missive by Dickens cannot be understated. As one biographer of the hospital put it, “Six weeks after the hospital opened, […] Charles Dickens published ‘Drooping Buds’, the first description of the Hospital for Sick Children. The effect was immediate. Mothers came hurrying to Great Ormond Street with their sick children; they now knew and believed, in Dr. West’s own words, ‘that those who asked for the suffering little ones were indeed to be trusted with so precious a deposit’”7 Fifteen years later, Dr. West would reminisce about the hospital’s beginning at its anniversary dinner:

Charles Dickens, the children’s friend, first fairly set her [Great Ormond Street] on her legs and helped her to run alone, and in a few eloquent words which none who have heard can ever forget, like the good fairy in the tale, he gave her the gift that she should win love and favour everywhere; and so she grew and prospered.8

Charles Dickens would remain a friend to the hospital for years to come. After capturing the hearts of his audience with A Christmas Carol, he began performing passages from it to raise funds for the hospital. He particularly would read the end, where a miser’s heart had been changed and in doing so, a small sickly child was saved. The character, Tiny Tim, became a symbol of the hospital.9 The child who could be saved, if only there was someone to lend a hand.

Great Ormond Street Hospital, as it has come to be known, was the first of its kind in the UK, the US, and Canada. Physicians visiting from the United States took back what they had seen at Great Ormond Street Hospital and founded hospitals across the US in its image. In many ways, Great Ormond Street Hospital is the basis for our current system of pediatric in-patient hospitals. This transformative institution was on the verge of collapse until an author took up his pen and wrote the hospital into the public’s heart. Great Ormond Street Hospital has never forgotten the benefit it gained from this literary gift; literature became a part of the hospital and has been a constant partner. Many famous authors followed Dickens, supporting the hospital with gifts of money and their talents. Tiny Tim would remain the hospital’s standard bearer until Peter Pan, a boy who would not grow up, later flew into the picture.

Dr. West never forgot the power of stories. At a time when medicine was much more art than science, a physician often had little more than comfort to offer. Dr. West included this piece of sage advice in his writings:

I would not have you think that fairy tales are foolish to be told now that we have so many good and useful books for children […] God himself has formed this world full not only of useful things, but of things that are beautiful, and which, as far as we can tell, answer no other end than this, that they are lovely to gaze upon, or sweet to smell, and that they give pleasure to man.10

This advice has not only come to the aid of those caring for children, it has been a constant truth for the administrators of Great Ormond Street Hospital. This advice has shaped the practice of pediatric care.

References

- Kosky, Mutual Friends.

- Higgins, Great Ormond Street 1852-1952.

- Higgins.

- Higgins.

- Tomalin, Charles Dickens.

- Dickens and Morley, “Drooping Buds.”

- Kosky and Lunnon, Great Ormond Street and the Story of Medicine.

- Kosky, Mutual Friends.

- Boehm, Charles Dickens and the Sciences of Childhood.

- Kosky, Mutual Friends.

Citations

- Boehm, Katharina. Charles Dickens and the Sciences of Childhood: Popular Medicine, Child Health and Victorian Culture. Palgrave Studies in Nineteenth-Century Writing and Culture. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire ; New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

- Dickens, Charles, and Henry Morley. “Drooping Buds.” Household Words, April 3, 1852.

- Higgins, Thomas Twistington. Great Ormond Street 1852-1952. Odhams Press, 1952.

- Kosky, Jules. Mutual Friends: Charles Dickens and Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1989.

- Kosky, Jules, and Raymond J. Lunnon. Great Ormond Street and the Story of Medicine. London : Cambridge: Hospitals for Sick Children ; Granta Editions, 1991.

- Tomalin, Claire. Charles Dickens: A Life. London: Penguin, 2012.

JOSPEH DEBETTENCOURT is a medical student at Rush Medical College in Chicago, Illinois, with an interest in pediatrics. He attended Northwestern University where he received a BA in Theatre and Pre-Medical Studies. He has worked as a professional actor, designer, and carpenter, as well as a standardized patient, and medical researcher.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 10, Issue 2 – Spring 2018

Fall 2017 | Sections | Hospitals of Note

Leave a Reply