Michael Ellman

Chicago, IL, United States

|

|

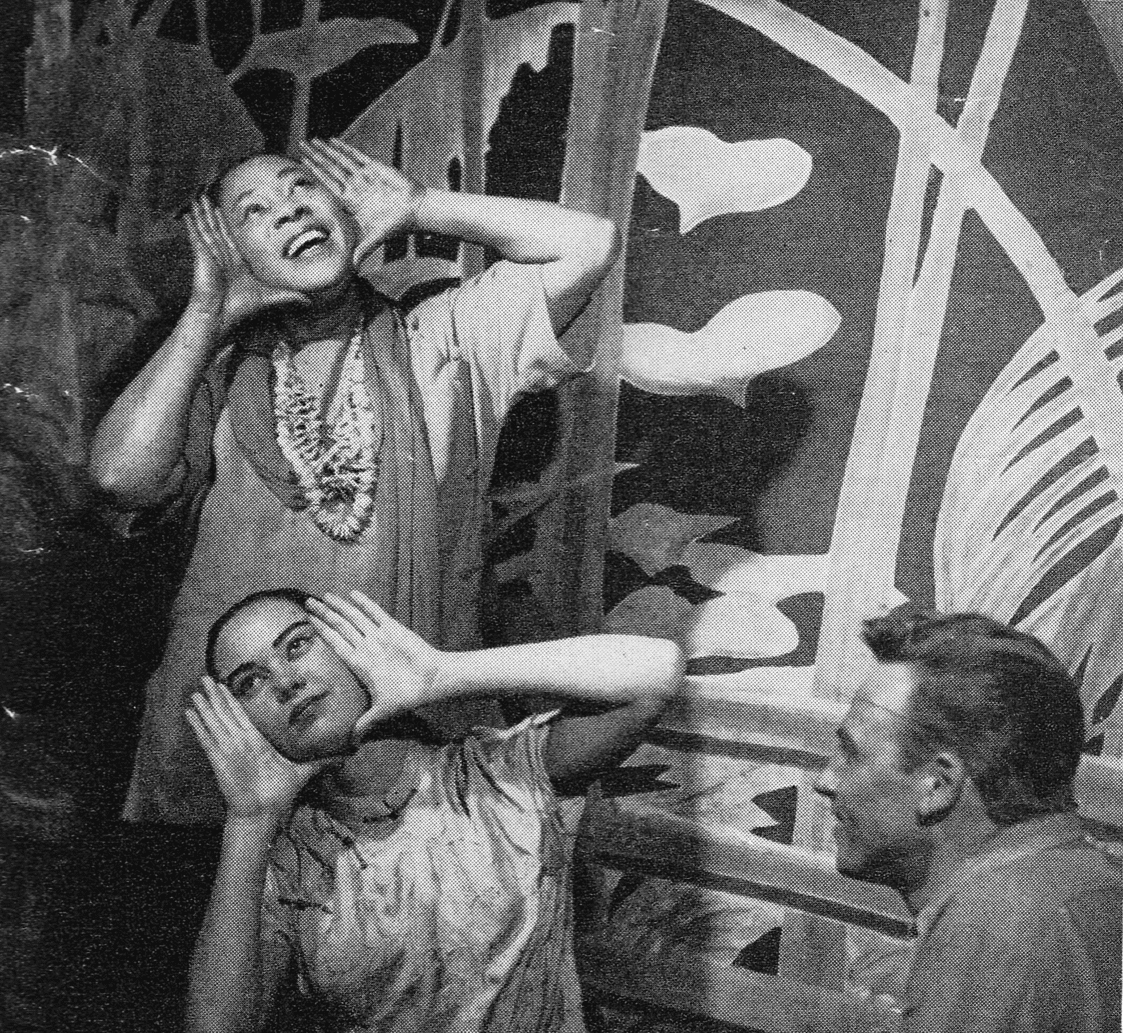

South Pacific, 1950. |

“Joseph Cable, at your service! U.S. Marines, World War Two, retired—at ease, Doctor. Let’s be casual, shall we?” My patient is tall and ramrod stiff, his hair an isthmus of bristle above his forehead.

The psychiatry unit interview room is small—a tired square table and two wooden straight-backed chairs. The light is fluorescent and hard, like an interrogation room. The patient— middle-aged, clean-shaven, and presentable—waits for me as my fellow students and Doctor Larry sit behind the two-way mirror to the left.

“Joseph Cable!” I say, scanning the medical chart open in front of me. “It says here you’re Frank Weatherston. Do I have the wrong patient?”

“Guess how many enemy ships we sank?” Joseph Cable, or is it Frank Weatherston, asks.

I remember not to enter into patient fantasies. Maybe this guy had multiple personalities, a popular topic in the medical journals stacked on my desk. I glance at the mirror, hoping to get direction from Doctor Larry, but instead retreat to the routine—family history, childhood memories, employment, and family issues.

It is the fall of 1963. I am a third-year medical student called Doctor Ted, starting my psychiatry month. Psychiatry should be easy—no night call and no scrubbing into the operating room. There are six students and Doctor Larry—probably the youngest doctor in the psychiatry section. A little pudgy, medium height, skin the color of granite from too much time inside and studying too hard for his Psychiatry board exams. He is self-assured and confident. Psychiatrists are confident. If I had said, “Larry, big fellow, you’re packing too much lard, let’s go running in the morning and work some of it off,” he would respond: “Fascinating suggestion—let’s go into why you brought that up,” ignoring his own problems and trying to help me with my insecurities.

I have taken the shuttle between the medical school and the private teaching hospital hundreds of times, but still the driver wants to check my ID. He sees me running pell-mell toward the bus stop, waits, opens the levered door, and asks for identification. I walk on the bus; one of my classmates, waves to me and says, “Yes, you can sit here.”

“You interviewed your patient quite well,” she says. “The guy’s different names are fascinating, but I don’t think he chose his other name at random. Here’s my idea about this Joseph Cable business.” I give her a blank look.

“Don’t you get it?” she says. “Lt. Joe Cable was the Marine from South Pacific, the musical, the movie, the book, James Michener—the fictional guy who gets killed but only after he fell in love with Bloody Mary’s daughter. The same guy who traveled with the Frenchman, Emile de whatever, the Some Enchanted Evening guy, to spot Japanese ships.

Doctor Larry invites me to come right over to his red-brick townhouse. Of course, he has heard of The Tales of The South Pacific. Mrs. Larry lets me in. “Larry’s in the basement with his weights and told me to offer you a beer until he lifts his thousand. Be comfortable. It’s my time to go upstairs and read a bedtime story to Larry Junior, unless you want to volunteer? Do you know Go Dog Go?”

She laughs and disappears. Larry comes up and expounds for an hour about our patient, Frank or Joe. He could be standing at a podium in front of contemporaries explaining brain chemistry.

“Play it safe, don’t upset him and don’t tell him the fictional Cable was killed. I worry about schizophrenia. Go slow—call him Frank. Take the seat near the door and leave it ajar. That’s a rule you always need to remember in psychiatry. He’ll be a challenging patient, and thanks for coming here tonight with this astounding information.”

Frank is still Lieutenant Joe. There is no military service mentioned on his medical record: 4F for flat feet and thyroid problems, but an accounting degree, working for his father, living with his wife and mother-in-law. “Yes, I like musicals,” Frank says. “South Pacific? That’s the best one to join. Better than Oklahoma and Showboat,” and he starts to sing. “Dites-moi Pourquoi—tell me why you’re asking me such a question, la-la-la.”

I also like Broadway musicals but it is better not to sing along. It seems to me, however, that if you happen to be delusional, a war hero with song in his heart is not so bad.

“Au contraire,” Dr. Larry tells me later. The delusions seldom disappear; they cycle in severity and may occupy much of Frank’s life.

Sometimes I see Frank with Doctor Larry and other times by myself. “I’m beginning to see the problem,” Frank says. “Maybe, if I resign my commission, I can leave here and go home. I forgive the Frenchman who left me wounded on the island. But I was too tough to die.” Frank leans forward, rigid straight back, his face in mine—and tells me he remembers everything, whether it happened or not. And I, Mr. Third Year Medical Student, do not know if this is progress or brain function going even further haywire. Bedside perspicuity, it seems, is trickier than memorizing a chapter in Cecil’s Textbook of Medicine.

“Frank’s delusions don’t vary, even when we present him with facts—it’s called anosognosia,” Doctor Larry teaches me. “This lack of insight or self-awareness is difficult to overcome, but we need to make the effort. Go back and detail his childhood and adolescence. I’m sure we’ll find a defining event that triggered his illness. It might give us something that we can work on.”

“Emile Kraepelin in 1887,” I tell everyone at our next student meeting, “used the term dementia praecox for patients with symptoms we now associate with schizophrenia. Doctors that came later recognized the patient’s anosognosia, a word I’m sure you’re all familiar with,” I say with a straight face. “And schizo and phrene come from the Greek words ‘split’ and ‘mind’, although the idea that schizophrenics have a split or a multiple personality is a common misunderstanding.”

Medicine at the County Hospital follows my psychiatry rotation. There is no breathing space in medicine, but I am allowed to see Frank as an outpatient once a week.

Unlimited visibility and warmth bathe that Friday in Dallas, Texas—it makes the replays of the assassination even more vivid. November 22, 1963, like Pearl Harbor, becomes another day which will live in infamy.

“Doc, could you come outside for a moment,” our clinic administrator asks me. “If you want me to call the police, let me know.”

Frank stands at attention outside the clinic in a uniform of something or other—Boy Scout medals pinned on an Army Surplus shirt, a plastic bayonet sitting vertical on the left side of his belt. The outdoor gloom fingers its shadow on his determination—his eyes colored red, his brows set high. Frank’s presence should not have surprised me—but it did.

“Doctor Ted, my friend, come with me to pick up Doctor Larry. The three of us are going to the Russian consulate and do some damage. That’s an order! The Russians killed our President and we need to strike back.”

“Absolutely, Lieutenant Cable,” I say, looking Frank in his eyes. “Let’s telephone Doctor Larry first and tell him our plans.”

I make my apologies to the staff and walk with Frank to the street and the shuttle. His purposeful stride devours the distance, hands folded behind his back, his gait rhythmic like an academic exiting the library with new found knowledge. We sit near the front—Frank leans forward and sings From the Halls of Montezuma . . . The driver, an ex-marine himself he tells me, mouths the words, but the other passengers, huddled together like pilgrims at a Sunday church service, remain mute. The death of our President lays heavy crepe on speech and song.

Doctor Larry meets us under the hospital portico and smiles. He gently removes the bayonet and places his hand on Frank’s back, guiding him to his old inpatient room.

“We understand your anger,” Doctor Larry says, “but it’s not up to us to stop the madness.” I believe at that moment Doctor Larry is talking to the world at large. He writes the order for sedation.

“Maybe progress will come, but not yet; maybe the world will correct its spin, but not yet,” Doctor Larry says to me. “We needed to turn back the clock for our President and re-wire the mainspring for Frank, but time doesn’t offer concessions.”

The confident thoughts I have about medicine and the state of the universe have come and gone like the search for Prester John and the empire of Atlantis. Franklin Roosevelt once said: when you run out of rope, tie a knot at the end and hang on.

Mrs. Larry telephones and invites me for Thanksgiving dinner. “Prayer and good food will provide serenity. Fortitude also,” she says.

MICHAEL ELLMAN, MD, is a retired physician, Professor of Medicine at The University of Chicago, and writer. His stories have appeared in many journals including Black Heart Magazine, Third Wednesday, Hektoen International, Grey Sparrow Journal, etc. and are collected in a volume titled Let Me Tell You About Angela. His novel Code-One Dancing was published in 2016 by Windy City Publishers.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 10, Issue 3– Summer 2018

Fall 2017 | Sections | Fiction

Leave a Reply