Annabelle S. Slingerland

Leiden, the Netherlands

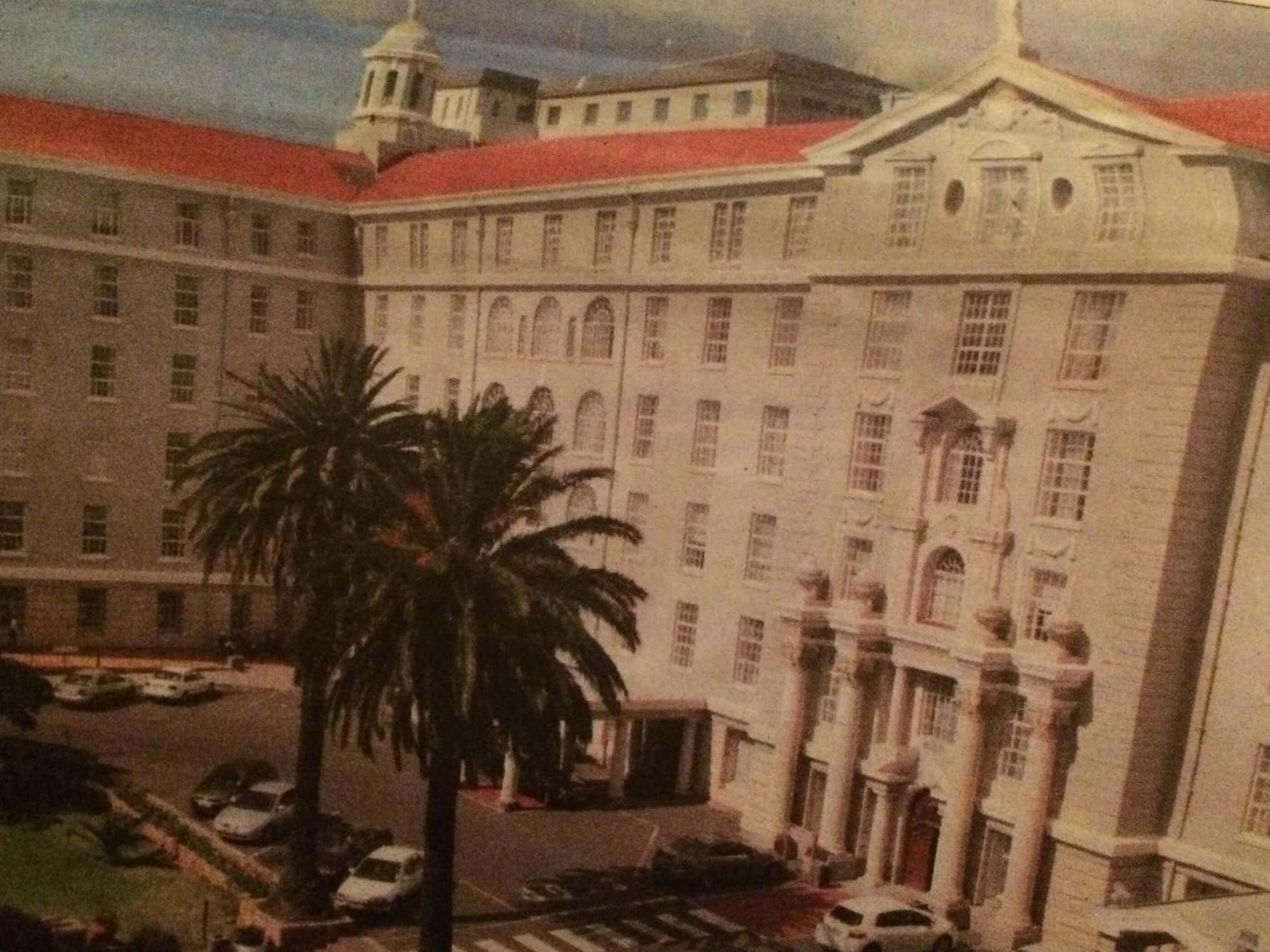

Façade of Groote Schuur Hospital

Beginnings

The Groote Schuur Hospital in South Africa’s Cape Town sits on a site first discovered in 1488 by the Portuguese Bartolomeu Dias. He called the peninsula Cabo Tormentosa (Cape of Storms), a good description of a site where the notorious South-Easter wind wrecked many ships. Later the Cape became Cabo de Boa Esperance (Cape of Good Hope) because the good anchorage offered an ideal stop for battered ships and malnourished sailors. In time the sandy beaches and rich vegetation prompted voyagers to call it the Tavern of the Seas, as the Cape’s temperate climate allowed year-round cultivation of lemons to provide a cure for the inevitable vitamin C deficiencies that plagued sailors. Vasco da Gama, after many months at sea en route to Asia, lost 100 of his 160 crew members to scurvy, then called the Scourge of the Sea.

The location at the Cape continued to offer a healthy haven when Jan van Riebeeck of the Dutch East India Company (1652-1800) settled there in 1652. He built a fort and began work on the Company gardens. These surrounded a small hospital of simple canvas tents and later of wooden structures built against the fort’s wall. The staff of this makeshift infirmary, known as the Sieckenhuys, included a surgeon to treat patients, a Ziekentrooster to console them, and a sergeant to deal with suspected malingerers.

The Cape became an important station for sailors at the halfway point to the Indies. When diamonds were discovered at Kimberley in 1867 and gold in 1885, the promise of riches drew many more foreign explorers as well as doctors, teachers, ministers, missionaries, and engineers from every continent on earth. Workers arrived from neighboring African countries and other parts of South Africa, and many were densely packed into segregated neighborhoods.

Early hospitals

The early hospitals at the site, De Kazerne and then De Groote Hospitaal. were mainly dedicated to Cape troops, seamen, and the poor of Kaapstadt, as Cape Town was known in Afrikaans. In 1818, when Dr. Samuel Bailey returned from the Royal Navy, he paid for the first public or civilian hospital and named it after Governor Somerset, an important benefactor. This gave rise to the Somerset tradition, which emphasized service to the needy and the sick. Patients included slaves and residents of the local slums suffering from fevers, chronic diarrhea, delirium tremens, chronic hepatitis, dysentery, and bronchitis.

In 1862, this turreted yellow castle with a Tudor-style exterior and a Florence Nightingale-style interior morphed into the New Somerset Hospital. It still commands attention at the waterfront. The site would weather many more storms: the Anglo-Boer War of 1899, the South African War, the post-war depression, droughts, unemployment, and disease-ridden shanty towns. The troubled townships’ residents flooded into the Cape Flats. During the same time frame, the scavenging South-Easter wind was rechristened “Cape Doctor” to acknowledge its role in blowing smoke out of the overcrowded town.

A university

In the 19th century, Cecil Rhodes, the British Empire builder and first prime minister of the Cape Colony, bought the lands originally used to harvest and store grain by the Dutch East India Company. He rebuilt the outsized barn on a site a near the current hospital; bequeathed his residence to the next prime minister; and stipulated that the land was to be used to build a university and funds for Rhodes scholarships.

Because students at that time had to receive their degrees in Europe, the university only offered the basic courses such as anatomy and physiology. These were required to prepare students for further study, typically in Leyden or Edinburgh. But as the population grew it became clear that the basic science curriculum favored in Europe no longer served local needs.

By that time the second generation, despite its European ancestry, felt more firmly rooted in South Africa and longed for its own medical school. Accordingly in 1907 Barnard Fuller, president of the Cape of Good Hope branch of the British Medical Association, followed up on Rhodes’s vision by proposing “a great teaching university” and “a well-equipped medical school. This school opened its anatomy and physiology departments in 1912, but the outbreak of World War I delayed progress, and the first medical degrees earned on African soil were not awarded until 1921.

A new teaching hospital

It soon became apparent that the medical school also needed a teaching hospital. This led the University in 1926 to lease about 2500 acres from Rhodes’s former estate to build the Groote Schuur Hospital. The Wall Street Crash followed soon after its inception, and during the subsequent Great Depression the new hospital responded pragmatically by sponsoring charities and public health initiatives, and revamping the Company Gardens to serve their original purpose of nurturing preventive medicine. Despite financial constraints, the professors strived for the best clinical teaching and hands-on hospital training.

By 1938 the facilities of the hospital had become outdated, and it was decided to build a new modern hospital. Its façade of Corinthian columns, cherubs, Grecian urns, swags and wreaths reflected the preference of its architect F.D. Strong for the neo-classical style. But the structure was not devoid of African influence in that Rhodesian birds gazed down at the original water towers and the entrance to the Palm Court was flanked by two lion heads. The fountains on either side of the lily ponds bore tiles depicting African and Malay legends. The large windows, balconies, and verandas offered ample air circulation, and sunshine.

In this new hospital all patients received the same high level of care, and famous patients included Nelson Mandela and Robert Sobukwe, leader of the Pan African Congress. According to the Cape Argus, Groote Schuur was “so delightfully arranged that it was almost an incentive to be ill,” and patients would do anything to be admitted to “the People’s Hospital.” It was the first of its kind South of the Sahara, doctors loved to work there; and the Capetonians successfully raised funds to support it.

Unfortunately, the opening of the hospital coincided with the start of World War II, and even its aftermath posed significant challenges. The once flourishing seaport lost its luster; shanty towns arose; and these were frequently plagued by contagious diseases, gastroenteritis, malnutrition, and high infant mortality. Only after several years, when the first fulltime dean was a pathologist, did the faculty resume instruction in basic sciences and resurrect its pathology wing and museum, while government became able to fund and stimulate fundamental and applied research.

An African diamond forged in hardship

Following the Somerset tradition, the university began admitting colored and Indian students as early as 1939. All patients and personnel were treated equally regardless of race or socioeconomic status. Beginning in 1943 the clinical training facilities were made open to all races. Although other hospitals were segregated by race, Groote Schuur defiantly served all, resisting discrimination in salary, type of education, and training. Some staff members countered prevalent discriminatory practices by offering to pay tuition for its victims and inviting students and colleagues into their homes. Groote Schuur hid the records of wounded protesters who gratefully referred to Groote Schuur Hospital as a sanctuary.

Groote Schuur also became the hospital of choice for victims of drug and alcohol abuse, as well as of stab wounds; and even Prime Minister Verwoerdt was treated there after being impaled in Parliament. The hospital also treated most of the traffic casualties that occurred after the high-speed highways opened. It responded with multiple injury service, ambulances equipped with ICU facilities, and an extra treatment unit adjacent to the regular emergency room. The worldwide wave of maladies – coronary artery disease and hypertension, rapidly led to expertise in treating diabetes and renal disease, and new specialties emerged in plastic-, thoracic-, and neurosurgery.

A history of making ends meet

Groote Schuur Hospital’s many attributes include resourcefulness in the face of financial constraints. In response to overcrowding it raised funds to help build the Red Cross Children’s Hospital in 1956. It had the New Somerset hospital receive “non-whites” as well. After the infamous 1960 Sharpeville massacre caused 269 casualties, including young children, the international outcry fueled criticism and cut foreign funding sources; but the mining industry and apartheid regime decided to invest in medical research to advance the country’s standing as a world leader in medicine.

Today South Africans are more accepting of non-whites, and the growing population of colored patients led to full desegregation of the hospital in 1987. The old sets of separate plates and cutlery are now on display in the hallways as silent reminders of the former racial divide.

Medical pioneers

The best-known South African medical trailblazer is the thoracic surgeon Christiaan Barnard, whose team carried out the first successful heart transplant in the world at Groote Schuur. Trained in the new field of medical transplants in Minnesota, Barnard, shared the exemplary work ethic of his predecessors at Groote Schuur by earning his Ph.D. degree in half the normal time. His supervisors in the U.S. were aware of the difficult circumstances that Barnard would face back home in South Africa and to gave him the generous gift of a heart lung machine as a farewell present.

Barnard had cleverly noticed a loophole in South African law: death was defined as brain death, regardless of whether the patient’s heart was still pumping. This was in contrast to many other countries where death was defined by a heart that was no longer vital. When Barnard returned to Groote Schuur his supervisors had him select a patient for the first heart transplant, even though he had done far fewer operations than his American colleagues. That operation took place fifty years ago on 3 December, 1967.

The ground-breaking work of Christiaan Barnard and his brother Marius, both from a family that opposed apartheid, had a palliative effect on South Africa’s international status as a pariah. Even Prime Minister B.J. Vorster observed that “we can link a moment of medical history to a positive image for the country.” Many more firsts were to follow, including the 1979 Nobel Prize for Medicine that was shared by Groote Schuur’s physicist Alan M. Cormack for his work in computerized tomography.

Today

The administration of Groote Schuur now follows the National Health Act of 2003 as well as offering equal access to health care for all. It still offers clothing, toiletries, and food parcels to discharged patients and their families when the breadwinner is temporarily disabled. Chaplaincy House and Kerhuis provide accommodations for relatives of patients from out of town. A band provides auditory treatment for patients, following Christiaan Barnard’s suggestion that Brahms could cure more patients than many doctors.

The classical revival architecture of Groote Schuur Hospital transformed into the Provincial Heritage Site of the Western Cape in 1996. Chris Barnard’s original operating rooms are the main attraction in the visitor-magnet now known as “The Heart of Cape Town Museum.” It displays many letters from children asking Dr. Barnard about his work and whether he might help to save a precious pet animal. The rest of Rhodes’s former estate includes the university up the hill, where students can still study medicine. The modern, American-style Groote Schuur Hospital adjacent to the older structures continues to save lives, prevent disease, educate future generations of doctors and scientists, and attain even higher levels of excellence.

Acknowledgements

The author currently divides her time on patient care and research between Joslin Diabetes Center/ Harvard, Boston and Hospitals of Note. She got acquainted with Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town that merged her strive for best technology and public health. She swam from Robben Island to Cape Town’s Coast for charity, raising funds for TSiBA students’ scolarships, Red Cross Children’s Hospital, and awareness for the challenging circumstances in the field of diabetes in South Africa, steered by ISPAD’s Capetonian president Professor Joseph Wolfsdorf- currently at Boston Children’s Hospital, and Laure Norger, GSH Professor Francois G.E. Bonnici with Anke Diedericks,and their active patient-parent group. She is indebted and grateful to all unsung heroes- who paved the way, Groote Schuur and the University of Cape Town’s personel and board, as well as to the impressive National Library, the National Archives, and the Heart of Cape Town Museum, Hennie Joubert and Lance Howell, for the resources and keeping the legacy alive.

Also, last but certainly not least, she would like to thank Robin Seeley and Professor George Dunea and team for their edits to reduce a history too extensive and intriguing to be told in a nutshell.

Bibliography

- Groote Schuur Hospital, 75 Years of Caring 1938-2013, January 28th, 2013.

- Groote Schuur Hospital, Annual Report 2011-2012 (preceding its 75th anniversary), Western Cape Government Health.

- Groote Schuur Hospital, Management Communiqué Grotties’ Grapevine. Western Cape Government Health, February 9th, 2017

- In the Shadow of Table Mountain, a history of the University of Cape Town Medical School and its Associated Teaching Hospitals up to 1950, with Glimpses into the Future. Jan H. Louw. Struik, Cape Town 1969.

- At the Heart of Healing Groote Schuur Hospital 1938-2008. Anne Digby, Howard Phillips, Harriet Deacon, Kirsten Thomson. Jacana Media (Pty) Ltd, South Africa, Auckland Park, South Africa, 2008.

- History of Medicine in South Africa, basis of the accounts on Medical Affairs up to 1900. Dr. Edmund Burrow.

- History of the South African College, 1829-1918. Professor W. T.P.Kent et al. T.M. Miller, Cape Town, 1918.

- South African Medical Record. Presidential Address delivered before the Cape of Good Hope Branch of the British Medical Association, vol.5, p.97: March, 1907.

- The Somerset tradition. S. Silverstone Bailey, Bickersteth, J. Barry, M. Gelfand. S Afr Med J. 1965 Jun 26;39(23):511-4.

- https://www.gshfb.co.za/component/content/category/11-educational resources, accessed 5 may 2017.

- Nedcare Christiaan Barnard Memorial Hospital, Exposition, visited April 18th, 2017.

- Lost hospitals of the Cape. C. de Villiers, A.L. Keyser. S.A. Medical Journal Special Issue, June 29th 1983.

- The Barracks and Military Hospitals of the Cape Peninsula in 1825-1826. P.R. Kirby. S Afr Med J. 1969, 43 748-749.

ANNABELLE S. SLINGERLAND, MD, DSc, MPH, MScHSR, co-authored scientific international articles on physiology, public health and cost-effectiveness. On her USA journey through rehabilitation centers, she was impressed by veterans and both their medical and military history as in similar articles at Hektoen International portraying Alcatraz, Craighlockheart, and Westerbork.