Lynn T. Kozlowski

Buffalo, NY, United States

Early in World War II, George Orwell wrote the essay “England, my England,” commenting that as he was writing “highly civilized human beings” were flying overhead trying to kill him:

They do not feel any enmity against me as an individual, nor I against them. They are ‘only doing their duty’, as the saying goes. Most of them, I have no doubt, are kind-hearted law-abiding men who would never dream of committing murder in private life. On the other hand, if one of them succeeds in blowing me to pieces with a well-placed bomb, he will never sleep any the worse for it. He is serving his country, which has the power to absolve him from evil.1

Suppose now that Orwell, a smoker of roughly thirty hand-rolled, unfiltered cigarettes a day and dead at forty-seven from respiratory complications of tuberculosis,2 had written instead about the business of cigarettes: “. . . highly civilized human beings are making and selling cigarettes that can kill me. They do not feel any enmity against me. . . . They are ‘only doing their duty, as corporate citizens.’” They are “kind-hearted law-abiding men and women who would never dream of hurting me in private life,” yet “if one of them happens to bring about my death, he will never sleep any the worse for it. He is serving his corporation and engaging in a legal business, selling a legal product subject to regulation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which collectively has the power to absolve him from evil.”

It is shocking to link a product that causes premature death of large numbers of people to the actions of civilized citizens who feel no remorse over these deaths from smoking. A kind of evil has taken place in a system where responsibility is absolved by a technicality because the product they sell is legal.

Is this an unfair comparison?

Since the 1980s, cigarettes have been recognized as “lethal when used as intended and kill more people than heroin, cocaine, alcohol, AIDS, fires, homicide, suicide, and automobile crashes combined.”3 Orwell called war “murder” but tobacco cigarettes could be seen as a kind of involuntary manslaughter, raising questions about what responsibility applies to the continued business of making, selling, and trying to deal with or control cigarettes as a legal product.

Orwell himself would not have worried much about the health effects of smoking as he puffed on his cigarettes. Sir Richard Doll observed that before the 1950s even physicians were not very worried about smoking as a cause of illness. Doll himself was a smoker in the late 1940s when his research began, and he expected it would show that air pollution was the major cause of lung disease in England.4 He stopped smoking cigarettes because of his research;5 and the seriousness of cigarette-caused death and disability has now been recognized for decades.6

The lethality of smoking

The 2014 Report of the Surgeon-General concludes, “The burden of death and disease from tobacco use in the United States is overwhelmingly caused by cigarettes and other burned tobacco products; rapid elimination of their use will dramatically reduce this burden.”6 One striking measure of the lethality of cigarettes describes the numbers of individuals per 100 dead and alive at 80 years after birth. There are 32 of 100 added deaths for women and 35 of 100 added deaths for men from smoking.7 Quitting smoking can add years to the life of a smoker.7 Smokers who quit by age 30 gain on average 10 years of life which takes their risk of premature death to the level of a never smoker. Those who quit by 40 gain 9 years of life. Worldwide, promoting smoking prevention and cessation continues to be an urgent public health issue.8

Other complexities

Given the number of smokers who have quit smoking, some will argue it is the smokers’ fault that they continue to smoke. This framing acts also to provide absolution from blame, but it is too facile to blame personal responsibility and ignore corporate responsibility. Increasingly, smokers are individuals with mental illness or heavy users of alcohol and other psychoactive drugs.9 And virtually all smokers begin to smoke in their adolescence or younger, when cigarettes are not a legal product for them to purchase.6 Even so, it is hard not to hold the smokers themselves accountable for continuing to smoke. Yet for surviving loved ones, a premature death from smoking is as terrible as a death suffered in war.

Ignoring emergencies

The social and health commitments made by cigarette makers and their support for current governmental regulations should be judged by the direct and effective efforts they themselves put into reducing the use of tobacco cigarettes. This is not an argument to ban cigarettes, but rather for the pursuit of multiple measures to reduce their use as soon as possible.10

Corporate players should appreciate that the current course of action for their legal product is not advancing public health. Governmental regulators and anti-tobacco public health groups also have dealings with cigarettes and should be prepared to accept responsibility for their own policies and practices that might act to promote the continued dominance of cigarette smoking. Just before entering into World War II, the U.S. recognized that its military was seriously under-equipped and that a new rapid, industrial-mobilization system was needed. The old way of doing things would be too slow to provide the material to supply a neglected military.11 “Business as usual” would not have gotten the job done in time. A new process simplified rules, fast-tracked possible solutions, and took risks. In a similar way, governmental regulators, the tobacco industry, and the public health community needs to be doing all they can to drive cigarette smoking to a minimum as rapidly as possible.

Others have made the case that for tobacco-caused deaths “business as usual” is an unsupportable position.12 Recently 121 health groups sent an open letter13 to PMI (Philip Morris International), calling for them to “immediately cease the production, marketing and sale of cigarettes.” The letter argues: “PMI, its shareholders, and you personally [the corporation president] have been enriched while knowingly killing your customers. You have it in your immediate power to change the fate of millions of people, perhaps hundreds of millions. Do the right thing by immediately ceasing the production, marketing and sale of cigarettes.”

|

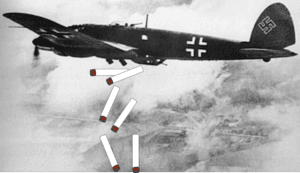

| Picture of German bomber during World War II altered by author to show cigarettes as if they were bombs. |

Many of the signatories of the open letter, however, have taken positions that oppose the promotion of alternative tobacco/nicotine products (smokeless tobacco and e-cigarettes) which are very much lower in harm than cigarettes and that can reduce the overall health costs of tobacco use.14 While it is encouraging that the new Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Commissioner has now offered explicit support15 for the inclusion of such “tobacco harm reduction”10 as part of the strategy to reduce the public health impact of cigarettes, this needs to take place urgently. However, FDA’s tobacco law16 offers significant challenges to the timely marketing of lower-harm tobacco/nicotine products.17 And the FDA law remains focused on the seeming regulatory ability to one day require only trace-nicotine content cigarettes.18 But one should doubt that this big business or its customers will in the near term (the next several years) or ever acquiesce to mandatory trace-nicotine cigarettes.17,19

The present variation on Orwell is offered as another kind of call for action. Following the orders of one’s country, corporation, commission, or health group may seem to absolve one from doing evil. But individuals can make moral decisions about the ethics of how they participate in a war20 or a “public health” enterprise. Members of society, tobacco growers, executives, and workers, stockholders, regulators, and public health groups need to focus on the major harm caused by cigarette smoking and be mindful of their own possible role in prolonging the continuation of smoking. All of the players in the business of dealing in or dealing with cigarettes should think less about “business as usual” and more about taking action as soon as possible to reduce the continued health emergency from smoking.

Image

Picture of German bomber during World War II altered by author to show cigarettes as if they were bombs. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/6f/Heinkel_He_111H_dropping_bombs_1940.jpg

References

- Orwell G. England Your England. 1941; http://orwell.ru/library/essays/lion/english/e_eye. Accessed: September 10, 2014

- Ricks TE. Churchill and Orwell: the fight for freedom. New York: Penguin Press; 2017.

- American Cancer Society. Smoke Signals: The Smoking Contrlol Media Handbook. American Cancer Society; 1987.

- Doll R. Tobacco: A medical history. J Urban Health. 1999;76(3):289-313.

- Doll R, Hill AB. The Mortality Of Doctors In Relation To Their Smoking Habits: A Preliminary Report. The British Medical Journal. 1954;1(4877):1451-1455.

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. The Health Consequences of Smoking-50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2014.

- Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):341-350.

- Jha P, Peto R. Global Health: Global Effects of Smoking, of Quitting, and of Taxing Tobacco. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(1):60-68.

- Truth Initiative. Business or exploitation? tobacco and social justice. 2017; https://truthinitiative.org/news/business-or-exploitation-tobacco-and-social-justice?utm_source=Truth+Initiative+Mailing+List&utm_campaign=12be52b022-NEWSLETTER_065_2017_08_25&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_c91fd8a5c5-12be52b022-70900921. Accessed:August 24, 2017.

- Kozlowski LT, Abrams DB. Obsolete tobacco control themes can be hazardous to public health: the need for updating views on absolute product risks and harm reduction. BMC Public Health. 2016.

- Herman A. Freedom’s forge : how American business produced victory in World War II. 1st ed. New York: Random House; 2012.

- Cummings KM, Gustafson JW, Sales DJ, Khuri FR, Warren GW. Business as usual is not acceptable: Justice for Injured Smokers. Cancer. 2015;121(17):2864-2865.

- Open letter from 121 health groups to PMI. https://www.unfairtobacco.org/en/open-letter-quitpmi/. Accessed October 3, 2017.

- Levy DT, Borland R, Lindblom EN, Goniewicz ML, Meza R, Holford TR, Yuan Z, Luo Y, O’Connor RJ, Niaura R, Abrams DB. Potential deaths averted in USA by replacing cigarettes with e-cigarettes. Tob Control. 2017 Oct 2. pii: tobaccocontrol-2017-053759. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053759.

- Warner KE, Schroeder SA. FDA’s Innovative Plan to Address the Enormous Toll of Smoking. JAMA. 2017 Sep 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.14336.

- United States Code. Family Smoking Prevention And Tobacco Control Act. Stat 1776. United States, 2009.

- Kozlowski LT. Prospects for a nicotine-reduction strategy in the cigarette endgame: Alternative tobacco harm reduction scenarios. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(6):543-547.

- Donny EC, Hatsukami DK, Benowitz NL, Sved AF, Tidey JW, Cassidy RN. Reduced nicotine product standards for combustible tobacco: building an empirical basis for effective regulation. Prev Med. 2014;68:17-22.

- Hall W, Kozlowski LT. The diverging trajectories of cannabis and tobacco policies in the United States: reasons and possible implications. Addiction. 2017 May 22. doi: 10.1111/add.13845.

- Steinhoff U. When may soldiers participate in war? INTERNATIONAL THEORY. 2016;8(2):236-261.

LYNN T. KOZLOWSKI, Ph.D. is professor of community health and health behavior at the University at Buffalo, State University of New York, School of Public Health and Health Professions. He was dean from 2008 to 2014. His work concerns tobacco use and ranges from empirical studies to projects on ethics, history, and policy. He has published in Science, Nature, New England Journal of Medicine, Lancet, JAMA, Addiction, Science and Engineering Ethics, and Issues in Science and Technology. He contributed to Surgeon-General Reports and National Cancer Institute Monographs. He is a senior editor of Addiction and associate editor of Tobacco Control.

Leave a Reply