William Kingston

Dublin, Ireland

|

|

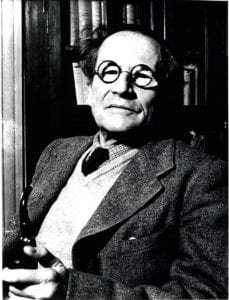

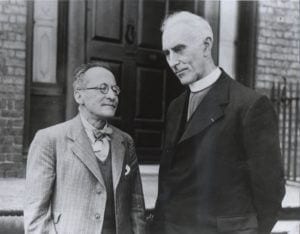

| Ewald, Born, Heitler & Schrodinger 1943, outside 65 Merrion Square (then home of STP). Courtesy of DIAS. | E. Schrodinger, 1955. Courtesy of the Irish Press. |

In 1943 a series of lectures was delivered in Trinity College, Dublin, which had profound scientific and medical consequences. Their title was What is Life? and it is no exaggeration to claim that they led to a revolution in our knowledge and use of genes. The lecturer was Erwin Schrödinger, who had shared the Nobel Prize with Dirac in 1933 for his contribution to wave mechanics in atomic physics. His new ideas called the attention of physicists to the potential for applying their knowledge and methods to biology.

For example, Schrödinger discussed how chromosomes ‘contain in some kind of code-script the entire pattern of the individual’s future development and of its functioning in the mature state;’ and moreover how their structures ‘are at the same time instrumental in bringing about the development they foreshadow.’

In less than a decade, several leading thinkers and researchers from both disciplines had combined their efforts to create the new field of molecular biology, which has led to some of the most remarkable advances in modern science.

But why was this world-renowned Austrian scientist in Ireland during World War II? Schrödinger had been an outspoken critic of the Nazi persecution of Jews, in fact one of the few prominent non-Jewish people in Austria to do so. This caused him to be dismissed from his professorship in Graz. The Irish Prime Minister, Eamon de Valera, had a dream of establishing an Institute of Advanced Studies in Dublin on the model of Princeton’s. At the time he was in Geneva on League of Nations business, and saw what Schrödinger’s prestige could do for his project. He instantly invited him to help found his Institute, which Schrödinger was glad to do, and in fact he stayed in Dublin for seventeen years.

|

|

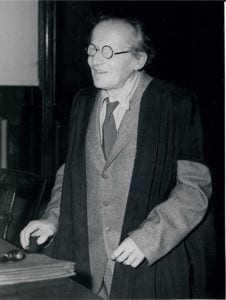

| E. Schrodinger, 1955. Courtesy of the Irish Times. | E. Schrodinger & Reverend Patrick Browne (Monsignor Pádraig de Brún) 1952, outside 65 Merrion Square (the home of STP). Courtesy of DIAS. |

The lectures were to be published by a Dublin firm but Schrödinger wanted to add an epilogue on ‘Determinism and Free Will’ dealing with their philosophical implications. He was almost as much a philosopher as a scientist, and it is plausible that his ability to be heard by biologists as well as physicists owed much to this. In this epilogue he accused ‘all official western creeds’ of ‘gross superstition’ because of their belief in a soul distinct from the body. Unsurprisingly, this displeased the highly conservative Archbishop McQuaid, whose influence was enough to ensure that the lectures would not be published locally.

Pressure was put on Schrödinger to remove the new material, but to the world’s advantage he stood firm and offered the book of the lectures to Cambridge University Press. Publication by them meant that the ideas immediately came to the notice of all the world’s scientists. One of these was James Watson, who has written that ‘from the moment I read What is Life? I became polarized towards finding the secret of the gene.’ Within ten years, he and Francis Crick had produced their famous paper on the double helix structure of DNA.

If Schrödinger’s ideas had been published in neutral Ireland in wartime, they could have had only local and limited circulation, probably with correspondingly little influence. As his biographer has written, ‘No doubt molecular biology would have developed without What is Life?, but it would have been at a slower pace and without some of its brightest stars. There is no other instance in the history of science in which a short semi-popular book catalyzed the future development of a great field of research.’ We owe a lot to the Archbishop for an unintended consequence of his disapproval of Schrödinger’s postscript to his Dublin lectures.

Additional information

In the photo credits, DIAS stands for Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies and STP for its School of Theoretical Physics, of which Schrodinger was Director in 1940-1945 & 1949-1956.

DR. WILLIAM KINGSTON was Professor of Innovation in Trinity College, University of Dublin, and is the author of six books and more than 70 refereed journal articles. Amongst these are ‘Antibiotics, Invention and Innovation’ (2000) in Research Policy 29 (6) 679-710 and ‘Streptomycin, Schatz v. Waksman and the Balance of Credit for Discovery’ (2004) in Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 59 (1) 441-462.

Leave a Reply