William Hazlitt, in one of his many essays that used to be inflicted on long-suffering schoolchildren, reminded his readers that “posterity are by no means as disinterested as they are supposed to be. They give their gratitude and admiration only in return for benefits conferred. They cherish the memory of those to whom they are indebted for instruction and delight.”1

This limited degree of immortality would leave out all those who must, as Sir Thomas Browne expressed it in his inimitably gorgeous but now unfashionable style, “be remembered in the book of God but not of man.”2 And nowhere is this better illustrated than in the hagiography of medicine, which immortalizes its acolytes for a great discovery, a new idea, a new way of doing things (“paradigm shift”) or eponymously for describing a new disease, a syndrome, or a physical sign. How fortunate then that at least some physicians who devoted their lives to caring for patients but making no great scientific splash are remembered because the Royal College of Physicians honors its members in Munk’s Roll,3 reprinting their obituaries going back to 1518.

One physicians thus remembered is William Babington, Irish born and initially trained there, then further educated at Guys hospital. He was later recalled to Guys from his position as assistant-surgeon at the Haslar military hospital in order to “undertake the office of apothecary.” We read in Munk’s Roll that “history does not supply us with a physician more loved and respected.. a man who to the cultivation of modern science adds the simplicity of ancient manners…whose reputation and rare benevolence of heart have long shed a graceful luster over a profession which looks up to him with the mingled feelings of respect, confidence, and regard.”3

We also learn that his “progress as a physician was rapid, and in the course of a few years he was in the possession of a large and lucrative city business. In 1811 his private engagements had become so numerous that he was compelled to resign his office at the hospital, and for many subsequent years was the acknowledged head of his profession in the city.” We are further told that while at the military hospital he was ordered to attend to prisoners of war “among whom a malignant jailed fever had broken out and he became subject to it and narrowly escaped with his life.”3

During the 1833 influenza epidemic, “though labouring under cough attended with great disability” he continued to visit his patients while “much oppressed and extremely weak… He then went to bed exhausted, became delirious, and was next morning in a hopeless state; the chest affection rapidly assuming the character of peripneumonia; the lungs becoming oppressed with mucus, which he was unable to expectorate… [so that] he died at his residence in the seventy-seventh year of his age.”3

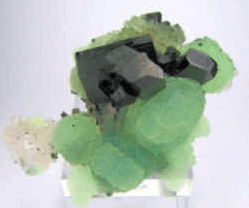

A statue of him was erected in St. Paul’s cathedral and “his death elicited a universal feeling of regret,” but his life also serves to bring us back to an era when physicians made time to pursue scientific endeavors unrelated to their profession. William Babington was also a mineralogist. He was a founding member of the Geological Society of London and served as its president from 1822 to 1824. At one time he bought an enormous collection of minerals from the Third Earl of Bute and became its curator. He has a mineral, Babingtonite, named after him, a calcium iron manganese silicate, very unusual in that iron completely replaces the aluminium typically present in silicate minerals. Found in volcanic rocks, its coloring is very dark green to black; and by official decree of the 190th General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (Section 18) it is the mineral or mineral emblem of the commonwealth.

References

- William Hazlitt: On the Fear of Death, in Table Talk, everyman’s Library, Dutton, New York,1908.

- Sir Thomas Browne: Hydrothapia, or Urn Burial, in Religio Medici and other writings, JM Dent and sons, London,1906.

- Munk’s Roll. Lives of the fellows. rcplondon.ac.uk

Leave a Reply