Sylvia Karasu

New York City, New York, United States

In Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Birthmark, 1 Aylmer, “a man of science” leaves the somber, factory-like atmosphere of his laboratory to marry the beautiful Georgiana. Aylmer “had devoted himself, however, too unreservedly to scientific studies ever to be weaned from them by any secondary passion,” and seems to “require” the “intertwining” of the love of his new wife with his “love of science.”1 With this in mind, readers should not be surprised that he will need to return to the laboratory, albeit with his new wife as the subject of his experimental pursuits.

|

|

|

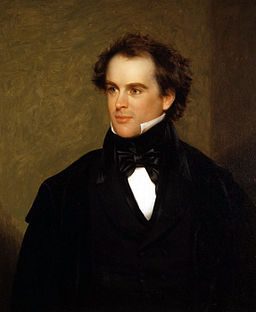

| Portrait of Nathaniel Hawthorne by Charles Osgood, 1840. (Peabody Essex Museum). (Public Domain) |

The first page of the short story ‘The Birth-Mark,’ by Nathaniel Hawthorne, published in March 1843, in The Pioneer. (digitized by Archive.org) (Public Domain) |

Statue of Nathaniel Hawthorne in Salem Massachusetts, his birthplace. Sculpture by Bela Pratt (1867-1917). (Public Domain) |

Shortly after his marriage, though, Aylmer develops an obsessive preoccupation, a “tyrannizing influence,” with a small birthmark on Georgiana’s left cheek—“the visible mark of earthly imperfection…”1 The birthmark was “deeply interwoven, as it were, with the texture and substance of her face.”1 In the shape of the “smallest pygmy” hand, it had never bothered Georgiana, who thought of it as a “charm” until she perceives Aylmer’s reaction–“a convulsive shudder.”1 She then insists that Aylmer remove it at all costs: “this hateful mark makes me the object of your horror and disgust…”1

Aylmer is only too willing to comply and fashions himself an alchemist who has dabbled in an “elixir of immortality.”1 Georgiana, portending the inevitable, has noticed “his most splendid successes were almost invariably failures…”1 Though Aylmer recognizes possible dangers, he is arrogantly “confident in his science.”1 Hawthorne’s gothic tale ends tragically: Aylmer’s remedy is ultimately able to remove Georgiana’s birthmark, but shockingly it results in her death.

Like the shape of the birthmark itself, the story has become a Rorschach for scholars. Hawthorne’s saga lends itself to interpretation from the perspective of evolutionary biologists, plastic surgeons, psychoanalysts, historians, philosophers, scientists, bioethicists, and feminists, among others, that foster diverse meanings and a “kind of radical ambiguity.”2 Why has The Birthmark continued to hold such a powerful grip on its readers?

For one, Hawthorne has chosen to mar the face of an otherwise stunning woman. The face is read “scientifically,” as it has been described as “marking the boundary between civilization and barbarism:”3 since the face is “admired for its beauty, so with savages it is the chief seat of mutilation.”4

Neurobiological researchers have found that the face holds particular interest:5 infants are more attracted to faces within minutes of birth than other stimuli, and adults even respond differently to faces with defects.6 Humans are biologically programmed to gauge attributes of personality, appearance, emotions, and predilections of total strangers merely on the basis of facial cues.5 Evolutionary researchers speculate that physical attractiveness—and particularly symmetry of features3–is used to make judgments about the health and quality of mate selection.7 Significantly, Aylmer is “not concerned with his wife’s character or her soul but rather…perfection for him is equivalent to physical beauty.”8 “There are many faces” wrote Spencer, “spoiled by…defects of skin, which, though they indicate defects of visceral constitution, have no relationship to the higher parts of nature….The saying that beauty is but skin-deep, is but a skin-deep saying.”9

When there are asymmetries in the face, such as caused by congenital malformations, injuries, or dermatological diseases, humans tend to stigmatize by staring, teasing, or even pitying.10 Stigma has been defined as “an attribute that is deeply discrediting” and makes the person “different from others.”11 “By definition, we believe the person with a stigma is not quite human.”11 As a result, those with a visible stigma are subject to discrimination and lack of acceptance and respect.11 Even after a plastic surgical repair, the person still does not acquire “a fully normal status, but a transformation of self from someone with a particular blemish into someone with a record of having corrected a particular blemish.”11

|

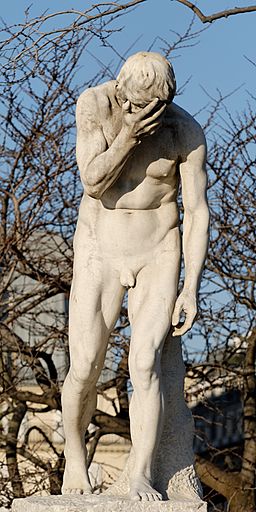

| “Cain” by sculpture Henri Vidal. 1896, Tuileries Gardens, Paris. (Public Domain): photograph by Marie-Lan Nguyen/Wikimedia Commons. |

Considerable superstition has flourished about the meaning of those with facial blemishes:12 God puts Cain under a curse for killing Abel in The Old Testament by marking him–considered the “mark of Cain”–for all to see his sin.13

As described by Hawthorne, Georgiana has a port-wine stain, also a called nevus flammeus,14 a common-enough lesion due to a benign genetic capillary malformation,15,16 usually on the head and neck, that occurs in 0.3% to 0.5% of newborn boys and girls.17,18 Typical port wine stains vary in size, shape, and colors that persist through life. In general, port-wine stains are an “aesthetic impairment”,10 but up to 10% of those with port-wine stains have the Sturge-Weber Syndrome, a non-inherited congenital neuro-cutaneous vascular disorder that may include serious ophthalmic (e.g. glaucoma) and neurological complications (e.g. seizures, mental retardation, headaches).10, 19

|

| Beautiful woman with port-wine stain birthmark on her cheek. Used with permission by iStock.com (purchased image for use.) Credit: khosrork |

Port wine stains (PWS) generally do not affect facial shape or contour, but nevertheless, “constitute a disfiguring flaw as well as a psychological affliction”20 and “a considerable cosmetic burden to the patient.”21 PWS are perceived as a “foreign element” on the face, even when there can be otherwise attractive facial features. Surveys have shown that these patients experience considerable psychological morbidity, including anxiety, depression, guilt, and embarrassment that does not resolve over time.20 Sometimes, though, the severity of distress can be out of proportion to the degree of disfigurement,21 such as seen in the reactions of Aylmer and ultimately of Georgiana.

In the mid-nineteenth century of Hawthorne, there were no treatments for removing a port-wine stain. It was not until the 1980s that laser treatments were introduced.17 The ‘clinical gold standard’ now for treatment is the use of a pulsed dye laser, sometimes combined with other therapies. Multiple treatments are generally required and rarely completely erase the port-wine stain.15,16,19

As noted, though, Hawthorne’s tale has been the subject of innumerable critiques, but with such divergent viewpoints, there is often “little agreement” about how to interpret the story22 that has “an archeology of motives.”23

Several sources have commented on Hawthorne’s profound psychological sophistication and understanding of the unconscious.23,24,25 Psychoanalytically, Aylmer is seen as an obsessive-compulsive personality24,25 for whom Georgiana “is but a wonderful possession”25 and whose main defense is intellectualization: he has sublimated his sexual curiosity into scientific inquisitiveness.24 Aylmer has been characterized as one of Hawthorne’s “intellectual sinners” but to some, he is not actually motivated by a passion for knowledge or science, but rather “by a single selfish passion…”26 It is not even clear that Aylmer is passionate about Georgiana: there is “an absence of love”27 in their relationship, and Georgiana is not “a normal wife” but rather a “compelling scientific experiment.”27 There is no indication, for example, that Aylmer has ever had a mature sexual relationship with Georgiana25 (nor, for that matter, with anyone else.)

What readers learn is that Aylmer’s obsession with Georgiana’s birthmark occurred only after their marriage.1 Freud has described some men who are unable to combine affectionate and sexual feelings for a woman because of developmental inhibitions.28 Says Freud, “Where they love they do not desire and where they desire they cannot love.”28 These men tend to need to protect themselves by debasing certain women and overvaluing others, with the result that they can achieve sexual fulfillment only with those whom they debase and despise.24,28 Hawthorne’s women have been described as reflective of “sexless idealization or innuendos of uncleanness.”23

|

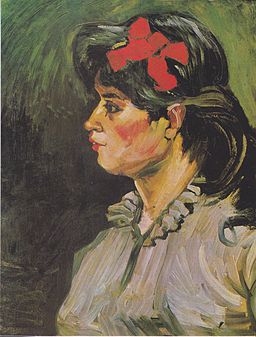

| Painting by Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. “Portrait of a Lady with Red Hairband.”(Public Domain.) |

Sources have commented on Aylmer’s anxiety about sexuality,24,25 particularly with references to Georgiana’s blood spilling “onto the narrative in a variety of ways, the most important being the fact that the birthmark is referred to as ‘the Crimson Hand’ or ‘the Bloody Hand”29 or even ‘the crimson stain.’ The bloody birthmark can be a stand-in for Georgiana’s deflowering, but hypothetically, these bloody images may relate to Aylmer’s reaction to Georgiana’s menstruation, often unknown to many men in nineteenth century America.30

Georgiana’s birthmark has also been seen as “property” in the context of the Adam Smith’s “developing market economy in antebellum America….(and) as property its ownership is transferrable or vulnerable, in this case to scientific experimentation.”29 As Aylmer “cleanses himself of the marks of his laboratory,”29 he marks Georgiana’s body with the imprint of his own fingers as he somewhat violently grabs her arm.31 As a result, “Georgiana is left open to his scientific depredations” whereby her body is “marked” by him and “the significant symptom of her deterioration is her loss of capacity to read the mark—from sense of play (e.g. “charm”) to object of horror and disgust.”31

Feminists have viewed the story as one of “sexual politics” that emphasizes the “powerlessness of women and the psychology that results” i.e., Georgiana’s developing self-consciousness, shame, and self-hatred.8 Mill, for example, has described the “mentality of submission” in nineteenth century women,32,33 a view that fits with Georgiana’s “indoctrination”33 by Aylmer as they live “exclusively within the confines of that marriage.”30 Likewise, there is an “overwhelming claustrophobia” that pervades the story’s atmosphere.31

The Birthmark has been seen as an “exposé of science”8 whereby it demonstrates that the “mythology of scientific research and objectivity finally masks murder:”8 Georgiana’s death becomes “just one more experiment that failed.”8 The story, though, is not necessarily an “indictment of science” because Hawthorne acknowledges its “extraordinary achievements.”33 Science becomes dangerously “in isolation from human society’s other influences…”33 The Birthmark, though, is seen as a “cautionary tale,”34 that had been assigned to members of the First Council on Bioethics: “The evils we face are intertwined with the goods we so keenly seek.”35 Freud noted, “It is not the aim of science either to frighten or to console.”28

Despite the diverse interpretations his tale affords, Hawthorne provides his own understanding in the voice of the narrator at its conclusion: Aylmer fails to “find the perfect future in the present.” It is a moral applicable to this era as much as it was for Hawthorne’s mid-nineteenth century.

Bibliography

- Hawthorne N. “The Birthmark.” In: Hawthorne’s Short Stories. Edited by Newton Arvin. New York: Vintage Classics (Division of Random House, Inc.) 2011, 177-193. (177, 178, 179, 180, 181, 186, 187, 190)

- Livington P. Literary Knowledge: Humanistic Inquiry and the Philosophy of Science. Chapter 6: “Literary Explanations.” Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1988, 200-242 (202).

- Gilman SL. Making the Body Beautiful: A Cultural History of Aesthetic Surgery. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999, xviii, xx, 152.

- Darwin C. Sexual Selection in Relation to Man. (Part III) Chapter XIX: “Secondary Sexual Characteristics of Man.” New York: The Modern Library, 1871, 867-890. (883)

- Little AC, Jones BC, DeBruine LM. “The Many Faces of Research on Face Perception.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society London Series B: Biological Sciences. 366(1571). 2011: 1634-7.

- Parsons CE, Young KS, Mohseni H, Woolrich MW et al. “Minor Structural Abnormalities in the Infant Face Disrupt Neural Processing: A Unique Window into Early Caregiving Responses.” Social Neuroscience. 2013 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2013.795189. (retrieved 11/5/16.)

- Hahn AC, Perrett DI. “Neural and Behavioral Responses to Attractiveness in Adult and Infant Faces.” Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 46(pt. 4). 2014: 591-603.

- Fetterley J. “Women Beware Science: ‘The Birthmark.’” In: The Resisting Reader: A Feminist Approach to American Fiction. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. 1978, 22-33. (22, 23-24, 30)

- Spencer H. “Personal Beauty,” (1854) In: Essays: Scientific, Political & Speculative (Library Edition, Volume II). London: Williams and Norgate, 1891, 387-399. (393-394)

- Masnari O, Schiestl C, Rössler J, Güttlein SK et al. “Stigmatization Predicts Psychological Adjustment and Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents with a Facial Difference.” Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38(2). 2013: 162-172.

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc., 1963, 1-51. (3, 5, 9, 48-49)

- Shaw WC. “Folklore Surrounding Facial Deformity and the Origins of Facial Prejudice.” British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 34, 1981: 237-246.

- May, Herbert G and Bruce M Metzger (editors). The New Oxford Annotated Bible: An Ecumenical Study Bible (Revised Standard Version) Genesis: 4: 1-16. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc., 1977, 5-6.

- Tannous Z, Rubeiz N, Kibbï A-G. “Vascular Anomalies: Portwine Stains and Hemangiomas.” (Invited Review). Journal of Cutaneous Pathology 37(Suppl 1), 2010: 88-95.

- Rozas-Muñoz E, Frieden IJ, Roé E, Puig L, Baselga E. “Vascular Stains: Proposal for a Clinical Classification to Improve Diagnosis and Management.” Pediatric Dermatology, 2016: July 25. doi: 10.1111/pde.12939. (Epub ahead of print.)

- Sharif SA, Taydas E, Mazhar A, Rahimian R et al. “Noninvasive Clinical Assessment of Port-wine Stain Birthmarks Using Current and Future Optical Imaging Technology: A Review.” British Journal of Dermatology, 2012; 167(6): 1215-1223.

- Chen JK, Ghasri P, Aguilar G, van Drooge AM, Wolkerstorfer A et al. “An Overview of Clinical and Experimental Treatment of Modalities for Port Wine Stains. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2012; 67(2): 289-304.

- Troilius A, Wrangsjö B, Ljunggren B. “Potential Psychological Benefits from Early Treatment of Port-wine Stains in Children.” British Journal of Dermatology, 1998, 139(1): 59-65.

- Sudarsanam A and Ardern-Holmes SL. “Sturge-Weber Syndrome: From the Past to the Present.” European Journal of Paediatric Neurology, 2014; 18(3): 257-66.

- Kalick SM, Goldwyn RM, Noe JM. “Social Issues and Body Image Concerns of Port Wine Stain Patients Undergoing Laser Therapy.” Lasers in Surgery and Medicine, 1981; 1(3): 205-213.

- Lanigan SW, Cotterill JA. “Psychological Disabilities Amongst Patients with Port Wine Stains.” British Journal of Dermatology, 1989; 121(2): 209-15.

- Tritt SM and Tritt M. “Chasing Perfection: Death Denial in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s ‘The Birthmark.’” PsyArt. (online journal): December 31, 2008. http://psyartjournal.com/article/show/m_tritt-chasing_perfection_death_denial_in_natha. (retrieved 11/9/16)

- Crews F. “Hawthorne, Freud, and Literary Value.” In: The Sins of the Fathers: Hawthorne’s Psychological Themes. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989, 258-271. (262, 266-67, 269, 270.)

- Proudfit CL. “Eroticization of Intellectual Functions as an Oedipal Defense: A Psychoanalytic View of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s ‘The Birthmark.’” International Review of Psycho-Analysis, 1980; 7: 375-383.

- Quinn J, Baldessarini R. “’The Birth-Mark:’ A Deathmark.” Studies in Literature (University of Hartford, West Hartford), 1981; 13(2): 91-98.

- Baym N. “The Head, the Heart, and the Unpardonable Sin.” The New England Quarterly, 1967; 40(1): 31-47.

- Crouse K. “Poison in the System: Symbols on the Body and The Body as a Symbol in Select Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne.” (A Thesis: Submitted to the University of Albany, State University of New York for Master of Arts: College of Arts and Sciences, Department of English, 2001. (7, 12, 17,19) http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.cornell.edu/pdfprintvie. (retrieved: 11/5/2016)

- Freud S. (1912) “On the Universal Tendency to Debasement in the Sphere of Love (Contributions to the Psychology of Love II.) In: The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XI . Translated and Edited by James Strachey. London: The Hogarth Press, 1957, 177-190. (180, 181, 183, 190)

- Weinstein C. “The Invisible Hand Made Visible: ‘The Birth-Mark.’” Nineteenth Century Literature (University of California Press), 1993; 48(1): 44-73.

- Zanger J. “Speaking of the Unspeakable: Hawthorne’s ‘The Birthmark.’” Modern Philology, 1983; 80(4): 364-371.

- Lawson K and L Shakinovsky. “A Frightful Object:” Romance, Obsession, and Death in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s ‘The Birth-Mark.’” In: The Marked Body: Domestic Violence in Mid-Nineteenth Century Literature. Albany: The State University of New York Press, 2002, 23-39. (25, 31, 34)

- Mill JS. The Subjection of Women. (Dover Thrift Edition Series). Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 1997, 14.

- Ekstein B. “Hawthorne’s ‘The Birthmark:’ Science and Romance as Belief.” Studies in Short Fiction, 1989; 26(4): 511-519.

- Kass L (Chairman). Council Discussion of ‘The Birth-Mark’ by Nathaniel Hawthorne. (led by William F. May), January 2002. https://bioethicsarchive.georgetown.edu/pcbe/transcripts/jan02/jansession2intro.html. (retrieved 11/5/16).

- Kass L (Chairman). Chairman’s Opening Remarks, First Meeting: January 17-18, 2002, The President’s Council on Bioethics, https://bioethicsarchive.georgetown.edu.pcbe/transcripts/jan02/opening01.html. (retrieved 11/5/16.)

SYLVIA R. KARASU, MD, is a Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medicine and a member of the Institutional Review Board of The Rockefeller University. The senior author of The Art of Marriage Maintenance (2005) and the textbook The Gravity of Weight (2010), Dr. Karasu is a cum laude graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and has her medical degree from Einstein College of Medicine. She is a Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association, a graduate of the New York Psychoanalytic Institute, an elected Fellow of the New York Academy of Medicine, and in private psychiatric practice in NYC.

Winter 2017 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply