Michelle Lott

Houston, Texas, United States

|

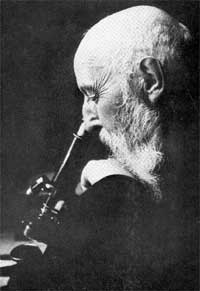

| Gerhard Amauer Hansen, Norwegian bacteriologist, who discovered Hansen’s Disease, or leprosy |

The old Indian Camp plantation in southern Louisiana was going to be an ostrich farm—at least that’s what folks were told, so as not to cause alarm. No ostriches ever came. Instead, it would become a home to those ostracized by society because they had a disease that struck a primal chord of fear in many and was believed by some to be a curse or punishment. Though it would hold several official designations over the years, most people simply referred to the property as “Carville,” the name of the closest small town.

For over a century, Carville would be the only inpatient hospital in the continental United States dedicated exclusively to the care and treatment of Hansen’s Disease (HD), the condition historically known as leprosy. At the time of Carville’s inception, leprosy was known to most people as an ancient affliction mentioned in the Bible. Dr. G. H. Armauer Hansen of Norway discovered that the disease is caused by Mycobacterium leprae in 1873. HD bears little resemblance to the descriptions given of the biblical illnesses, and those conditions were most likely not due to M. leprae infection.

The first seven patients arrived at Carville under the cover of darkness in 1894. The plantation was in a state of disrepair. Bats and snakes occupied the dilapidated buildings that sat decaying in the damp, humid air. The Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul were asked to come to Carville in 1896. Although the nuns were aghast at the deplorable living conditions and the harsh environment, they agreed to stay. As trained nurses, they provided for the medical treatment of the patients and tended to their spiritual and psychological needs.

Labeled with HD in 1908, John Early pushed Carville onto the national stage. He was transferred to different temporary quarantine locations including box cars and jails. No state or territory would permanently accept him. Desiring a refuge for all affected by HD, Early checked into the Willard hotel in Washington, D.C. in 1914. He mingled with guests, including prominent politicians, for several days. Then he called a press conference to announce his condition. As expected, panic ensued and the idea of a national leprosarium gained traction.

The federal government purchased Carville in 1921, and it became the United States Public Health Service Marine Hospital No. 66. Ironically, in securing a safe place for himself, Early “sentenced” most future HD patients to mandatory confinement at Carville for the next forty years. State laws governing quarantine varied. Some patients were brought to Carville by law enforcement—sometimes in shackles. Others were transported by hired escorts who were sometimes armed. Regardless of how they got there, removal from their homes was traumatic for patients. They frequently faced isolation and rejection from their spouses, families, and friends. Sometimes this isolation was self-imposed. Children were also sent to Carville, and they suffered the loss of their parents and vice versa. When admitted to the hospital, people were encouraged to change their names to hide their true identities. Many times staff members never knew the real names of patients—even their home towns were kept secret to spare families the stigma of the disease. These aliases were often carried to the grave.

Once inside, residents lost many of their basic civil rights. Men and women were completely segregated until 1921. They could not vote. Marriages were not allowed. The sterilization of patients was encouraged. Pregnant women were not allowed to hold or touch their babies after giving birth. Children born at Carville were put up for adoption unless other arrangements could be made. The quarantine was not absolute—patients could obtain a pass to leave. However, they could not use public transportation. State laws concerning travel differed with some requiring that patients get special permission to enter. People with HD were not allowed in Arizona’s air space, so they could not fly over that state. They were able to send and receive mail. However, all mail was baked in an oven before it was released into the general population.

Despite the indignities, residents of Carville formed their own independent, self-sufficient community. There was a canteen, post office, and power and water treatment plants. Residents held various jobs all over the property, and some set up their own businesses. Children attended school with patients serving as their teachers. From the dairy, bakery, and paint shop to crafts, carpentry, and a shoe shop, Carville had it all. There were also two chapels—Catholic and Protestant—and a jail for those who violated the rules. For recreation, residents had a golf course, a lake, and a theater group. They joined the local softball league—all games were at home. Children participated in scout troops. One sister gave piano lessons to kids, and the sisters threw birthday parties for them. Patients held an annual dance to celebrate the end of gender segregation. They also had their own Mardi Gras parades with decorated wheel chairs, costumes, and the tossing of doubloons. One enterprising resident, Sidney Levyson, who used the name “Stanley Stein,” started a newspaper in 1931. The Star’s motto was “Radiating the Light of Truth on Hansen’s Disease.”1 One of Stein’s main goals was to eradicate the use of the term “leper” and to replace the word “leprosy” with “Hansen’s Disease.” Of course, all copies of the paper had to be baked before they were mailed out to subscribers in 48 states and 30 countries.

Patients asserted themselves in their own ways. They might flout the rules and “forget” clinic appointments or not take their medications. The local Coca-Cola distributor feared a boycott of his product if he accepted returns from Carville, so he sent chipped and cracked bottles that he could refuse to take back. In response, residents cleverly used the bottles as flower vases, sugar dispensers, and bowling pins. They also lined garden borders and decorated graves with them. When Pepsi came along and offered to accept returns, residents switched to Pepsi. Throughout all of Carville’s existence, one of the main ways patients exerted control of their lives was leaving without permission. The most notorious method was “going under the fence.” A ten foot cyclone fence topped with barbed wire surrounded the premises. A culvert ran under one side of it. Patients cut the fence and made the hole bigger. They called cabs or friends to meet them. From there, they might attend Louisiana State University football games or go to a local bar.

Patients were expected to volunteer for medical experiments. Since M. leprae tended to grow well in cooler parts of the body, the infamous fever treatment was devised. Patients were put into a “hot box” that was heated to 140 to 155 degrees to try to destroy the bacteria. Side effects included delirium and nausea. Dr. Guy H. Faget was the Medical Officer at Carville in the 1940s. His specialty was tuberculosis (TB) which is also caused by a Mycobacterium. When he learned that a sulfone drug called Promin was being used in TB patients, he tried it at Carville. The majority of patients began to improve. More drugs were subsequently added to the HD armamentarium. Once patients tested negative for M. leprae for twelve consecutive months, they were free to leave. With effective treatment, some basic freedoms were restored. In 1946, residents regained the right to vote. In the 1950s, patients were allowed to wed and dorms were remodeled to accommodate married couples. They stopped baking the mail in the 1960s.

Dr. Paul Brand, a surgeon, arrived at Carville in 1966. He recognized that the insensitivity caused by HD led to chronic injuries and damage to extremities. He performed surgery to restore function to patients’ hands and feet, and the number of amputations done at Carville dropped dramatically. The methods he developed to treat plantar ulcers in HD patients are used today in the treatment of similar wounds in diabetic patients. In 1971, Dr. W.F. Kirchheimer developed a way to use armadillos as a model for human HD. Residents rejoiced at no longer having to serve as research subjects. Armadillos were the unofficial mascot of Carville.

By the 1970s, all admissions were voluntary. Outpatient clinics opened across the country to treat HD in 1981. There was no longer a need for Carville, and closure seemed likely. Long-time residents faced an uncertain future. Many had spent most of their lives there—it was their home. Carville was renamed the Gillis W. Long Hansen’s Disease Center in 1986 for the congressman who lobbied to keep it open. From 1991 to 1993, the Federal Bureau of Prisons opened a minimum security unit at Carville, and inmates lived alongside the aging HD occupants. In 1999, remaining residents were given a choice of a life-time stipend, relocation to a hospital in Baton Rouge, or staying at Carville.

Finally, it was decided that those who had been forcibly admitted could not be forcibly discharged. Also, anyone who had been forcibly admitted could come back to live out their years. A few still call Carville home. The Daughters of Charity ended their Carville mission in 2005. Today, the Louisiana National Guard runs a camp for at-risk youth at Carville. The National Hansen’s Disease Museum is also located there. No staff member or visitor ever contracted HD at Carville. Ninety-five percent of the world’s population is naturally immune to M. leprae infection. The precise mode of transmission remains unknown.

Notes

- Gaudet, Marcia G. Carville: Remembering Leprosy in America. (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2004), 38.

References

- Gaudet, Marcia G. Carville: Remembering Leprosy in America. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2004.

- Gould, Tony. A Disease Apart: Leprosy in the Modern World. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2005.

- Harrison, Laura. Secret People. Online video. Directed by Laura Harrison. Snag Films, 1998. “The National Hansen’s Disease Museum,” www.hrsa.gov/hansensdisease/

- Ramirez, Jose P., Jr. Squint: My Journey with Leprosy. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2009.

- What Remains: Life in a Leprosarium. Online video. AOL, Jan. 31, 2014.

- Wilhelm, John and Sally Squires. Triumph at Carville. DVD. Directed by John Wilhelm. PBS Home Video, 2008.

MICHELLE LOTT

Spring 2015 | Sections | Hospitals of Note

Leave a Reply