James L. Franklin

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

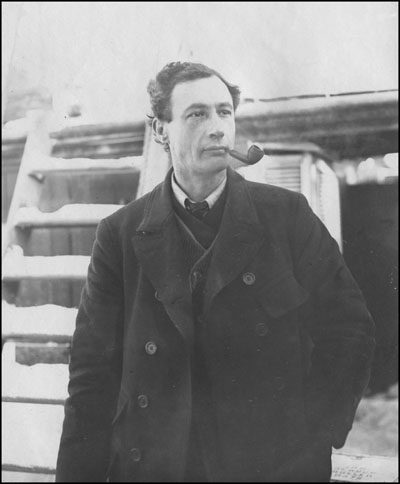

| Reginald Koettlitz |

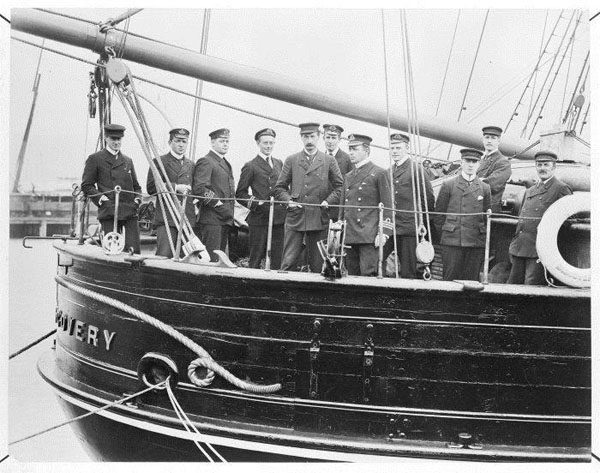

When Edward Adrian Wilson first went to the Antarctic aboard the Discovery he was officially the assistant surgeon to Dr. Reginald Koettlitz (1860 – 1916), the expedition’s senior surgeon, botanist, and bacteriologist. Wilson’s title was assistant surgeon, zoologist, and artist. On the Terra Nova Expedition, Wilson served as the chief scientist and not in the capacity of a surgeon. The senior surgeon aboard the Terra Nova was Edward Leicester Atkinson. This article addresses doctors Koettlitz and Atkinson and their experiences in Antarctica.

Aubrey A. Jones’s recent biography of Reginald Koettlitz bears the title Scott’s Forgotten Surgeon. This seems justified since books devoted to Scott and the Discovery Expedition as well as the biographies and writings of Edward Wilson contain only scant references to Koettlitz. In 1901, the year he was appointed senior surgeon to Scott’s Discovery Expedition, Koettlitz was forty-one years of age, four years older than Robert Falcon Scott and twelve years senior to his assistant surgeon, Edward A. Wilson. At forty-one, he was one of the oldest men in the expedition and had the most experience in polar exploration. In a letter written in 1900 to the famous Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen, he anticipated the tragic events on the Ross Ice Shelf in 1912: “How much better it would have been if someone had been placed in command who had former polar experience. The final result will, I fear, be much blundering and it will be muddled through à l’Anglais.”

Koettlitz was born on December 23, 1860, in Ostend, Belgium, to a Lutheran minister who moved his family shortly thereafter to Dover, England. He attended Guy’s Hospital in medicine and first took a position as a general practitioner in Butterknowle, a coal-mining village in County Durham in the North of England. In Butterknowle he cultivated an interest in geology and also made a collection of fossils from the coal-bearing strata of the region. In 1894, a posting in the British Medical Journal seeking the services of a physician for what would become the Jackson-Harmsworth Expedition to Franz Joseph Land served as his introduction to polar exploration. Franz Joseph Land, newly discovered, was an uninhabited archipelago north of Russia in the Arctic Sea. During three years in the arctic, 1894-1897, he had ample opportunity to learn to work around the idiosyncrasies of an erratic expedition leader, Frederick Jackson (1860-1938), gleaning valuable lessons in Arctic survival and also making important geological observations that ultimately earned him membership in the Royal Geological Society. He also cultivated the friendship of the Scottish explorer William Speirs Bruce and Albert Armitage; the latter would sail with him on the Discovery Expedition. While in Franz Joseph Land, he first met Fridtjof Nansen, who was returning from an unsuccessful attempt to reach the North Pole. Discussing his geologic findings with Nansen, they formed a bond that lasted until Koettlitz’s death in 1916. His appetite for adventure whetted, he joined an overland expedition to Somaliland and Abyssinia in 1898 as physician, geologist, and anthropologist. In 1900 he travelled up the Amazon allowing him to study the peoples along the river and the emerging rubber industry.

Koettlitz, like Wilson, married the year he left for the Antarctic. He had been courting Marie Louise Butez, and they were married on March 2, 1901 four months before the Discovery departed England.

There were problems for Koettlitz even before Discovery sailed. Though geology was his special area of expertise, he was given the responsibility of botany and the study of the phytoplankton. Disappointed and skeptical about the value of this endeavor, he nevertheless took his assignment seriously and, though recently married, spent the majority of his time prior to departure working with George Murray in the bacteriology department at Guy’s Hospital.

Robert Falcon Scott adhered strictly to the traditions of the Royal Navy both aboard ship and on shore. Officers and seamen dined and were quartered separately. In this environment, Koettlitz, though he had greater polar experience, did not feel at liberty to offer unsolicited opinions. He sensed an aura of class discrimination among the officers. As he wrote to his brother, “they were men who held very different world views.” He took polar exploration very seriously and found the attitude of the expedition leaders superficial. He had little sense of humor and refused to participate in hijinks associated with shipboard life. Refusing “to suffer fools gladly,” he soon became the recipient of mirth and the butt of many pranks. In the course of his medical duties, he successfully treated a dental abscess with a tooth extraction and somewhat theatrically performed the first elective surgery in the Antarctic, excising a large cyst from the cheek of seaman Charles Royds in the Hut Point Ward room. He was usually found at his laboratory bench and even taught himself the new technique of color photography, successfully taking the first color images of the Antarctic landscape. But it was all for naught.

When the Discovery returned to Portsmouth Harbor, a series of ceremonial engagements included an invitation to Balmoral Castle for Captain Scott to appraise King Edward VII on the results of the expedition. Scott presented Wilson’s superb sketches and Engineer-Lieutenant Skelton’s photographs but the historic color photographs taken by Koettlitz were not included. Koettlitz felt keenly snubbed when in 1905, Wilson, his medical assistant, published an article in the British Medical Journal, “The Medical Aspects of the Discovery’s Voyage” without inviting Koettlitz to participate in preparing the multivolume scientific report of the expedition. However, he was not forgotten in his hometown of Dover. He gave a lecture titled “Furthest South” to a packed audience in the Dover Town Hall and, according to the local press, held the audience spellbound for two and a half hours with many interruptions for hearty applause. “To add realism, a local man was dressed in Koettlitz’s polar clothing and withstood the two and a half hours without complaint” (Jones). His lecture included the first-ever presentation of his color slides. It was perhaps the only time they were seen in public and have since disappeared.

After returning to England, Koettlitz also was invited by Shackelton to join the Nimrod Expedition. However, having no means of independent support and a new wife he had been away from for three years, Koetlittz urgently had to find a medical appointment. Disillusioned by English class-consciousness, he emigrated to South Africa, first settling in Darlington, Cape Colony, where most of his patients were Afrikaans. Though he continued to correspond with Nansen, he ceased to participate in any further scientific endeavors. An attempt to rear ostriches for their feathers failed after a drought and a slump in the market for ostrich feathers. In 1915 he moved to a larger community, Sommerset East, where he bought a practice from a doctor who was on active military service. Within six months his wife died of heart disease and two days later Koettlitz, who was ill at the time, died of dysentery.

News of the death of Dr. Reginald Koettlitz spread around the world and obituaries appeared in The Lancet as well as local newspapers in London, New York, and Australia. He and his wife were buried in a Freemasons Cemetery in Cradock in an unmarked grave. In 1922 Rev. C. W. Wallace, the Rural Dean of the Cradock Anglican Church, and Captain Charles Royds, a colleague from the Discovery Expedition, remedied this by raising money for a memorial marker. Notably, Professor Fridtjof Nansen also contributed to this effort.

Koettlitz, through lack of humor and collegiality, was his own worst enemy. And yet he made a mark on polar exploration. A recent article in the Journal of Medical Biography by Henry Guly mentions several geographic points in Antarctica, as well as species of cuttlefish, algae, and cyanobacteria that bear his name. Guly summed up Koettlitz’s legacy thus: “Koettlitz was a doctor and explorer with a wide range of general scientific knowledge and as an amateur scientist he contributed to zoology, bacteriology, botany, geology and anthropology and he corresponded with leading scientists of the day in a way that, with scientific specialization, would never happen today. He seems to have been a difficult person which perhaps explains why his scientific contributions to the Discovery Expedition were not recognized.”

A contrary view is that expressed by William Speirs Bruce, the foremost Scottish polar explorer, who worked with Koettlitz on the Jackson-Harnsworth Expedition. Bruce described Koettlitz as “a man of great charm of character and an explorer of the best type, scientific, painstaking, and indifferent to notoriety or reward.”

References

- Jones, Audrey A. Scott’s Forgotten Surgeon. Scotland, UK: Whittles Publishing Ltd., 2011, p. 181.

- Guly, Henry. “Dr. Reginald Koettlitz (1860-1916): Arctic and Antarctic Explorer.” The Journal of Medical Biography. 2012; 20:141-147.

JAMES L. FRANKLIN, MD is a gastroenterologist and associate professor emeritus at Rush University Medical Center. He also serves on the editorial board of Hektoen International and as the president of Hektoen’s Society of Medical History & Humanities.

Summer 2015 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply