Anthony Ryan

Grace Neville

Cork, Ireland

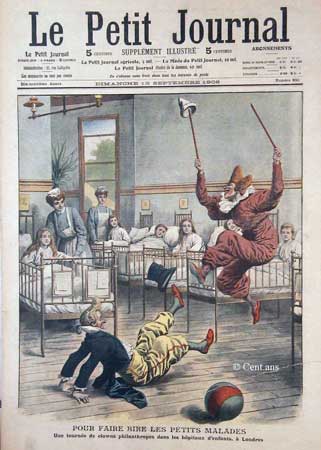

Le Petit Journal (LPJ) was a Parisian newspaper published from 1863 to 1944, with a circulation of over a million copies at the height of its popularity in the 1890s when it had a corresponding impact on a large swathe of the newly literate French population of the time.1 As well as publishing a daily copy, LPJ also featured colored illustrated weekly supplement. One such issue (September 1908) included a full front-page cover illustration and accompanying story about clowns entertaining children in a ward of a London hospital. The eBay acquisition of an original print of this edition prompted the authors to examine the history and routines of children’s hospitals, the story of nursing in the late Victorian era, and the evolution of clowning in the caring professions.

Although we are not told in which London hospital the clowns are performing, the LPJ illustration speaks volumes about attitudes towards sick children in hospital in the Victorian period. In a gas-lit ward, we see seven beds close together, although there are probably more, since we are seeing only one part of the ward. Only one child looks tired or listless and unable to participate in the fun: the others look lively and appear to be enjoying the performance of the two clowns. The setting has the appearances of a fever hospital or a sanatorium, with identifying bed numbers above each bed and patient vital signs in a clipboard at the end of each bed. This looks like a romanticized representation of a sick children’s ward, when one considers that only fifty years before the LPJ article, Dr. Charles West (1816-1898), the pioneer of English children’s hospitals, set up the first dedicated children’s hospital in England at Great Ormond Street, London, in 1851. And still, many years later Dr. West was still despondent about his lack of progress. “Forty-four beds!” he wrote, “when more than 21,000 children die every year in this metropolis under ten years of age; and when this mortality falls thrice as heavily on the poor as on the rich!”2

The smartly uniformed nurses in the impeccably clean ward in our illustration reflect the training of the Lady of the Lamp and Victorian focus on order and cleanliness. Florence Nightingale (1820-1910) was nearing the end of her long life at the time of the publication of the LPJ illustration. Her mission to the Crimean war had been precipitated by the terrible neglect of the British wounded in comparison to the French soldiers, championed by William Russell, The Times’ correspondent. He asked: “Are there no devoted women among us, able and willing to go forth to minister to the sick and suffering soldiers of the East in the hospitals of Scutari? Are none of the daughters of England, at this extreme hour of need, ready for such a work of mercy? Must we fall so far below the French in self-sacrifice and devotedness?” (The Times, 15 and 22 September 1854). His plea led to Florence Nightingale leading a taskforce to the Crimea. Six years later, the Nightingale School and Home for Nurses was established at St. Thomas’s Hospital. Nightingale’s health prevented her from accepting the post of superintendent of the School, but she used her experiences in the Crimea to establish her vision of nursing care through her book Nursing Notes (1860).

The LPJ illustration shows the focus on Victorian order with no visible toys and no play area. Another noticeable feature is the absence of parents and visitors. In 1894, Boston Children’s Hospital had only two visiting days for parents per week, 11 a.m. to noon on Wednesdays and 3 to 4 p.m. on Sundays for fathers only.3 At Massachusetts General Hospital in 1910, homesick children who cried too much for their parents were moved to isolation wards so as not to disturb the other patients. Most physicians practicing in this era considered childhood diseases to be caused by unhealthy environments and improper parenting. Removing children from deleterious home environments was considered therapeutic. The working poor were in a Catch-22 situation, forced to choose between visiting their children or reporting for work, and being branded either as bad parents or bad workers. In contrast, wealthy parents who could afford private rooms for their children had unlimited visiting hours.

It was not until the 1950’s that the work of John Bowlby (a psychologist, psychiatrist, and psychoanalyst) and James Robertson (a psychiatric social worker and psychoanalyst) revolutionized the hospital environments for children.4 Bowlby developed the classic theories about maternal separation while Robertson focused on the psychological effects of the separation of mother and child due to hospital admission. Together, they derived the classic theory about the phases of “protest,” “despair,” and “denial” (Bowlby called this last stage “detachment”) through which small children pass when isolated from their mothers for a length of time. As a result of their observations, today’s’ children’s wards and hospitals encourage parents to be with their children in hospital at all times, even sleeping alongside them in the planning and implementation of their child’s care.3

The LPJ illustration entitled, “Pour faire rire les petit malades” (To make the little sick children laugh) refers to the original short story by Académie Française member, Jules Claretie (1840-1913) that was carried in the LPJ of November 1907. Claretie recounts the heart-rending Parisian tale of seven-year-old François who is sent home from school with a dramatically high temperature (heavy head and boiling hot hands). He becomes lethargic and silent, refuses all food and drinks (herbal drinks, syrup, broth), and lies tossing on his bed. His working-class parents are distraught and fear the worst. They beg him to tell them if he wants anything. He surprises them by announcing that he wants to see the clown Boum-Boum, whom he had enjoyed in a circus on Easter Monday. The father gathers all his courage and goes to see Boum-Boum who readily agrees to accompany him to visit little François. Seeing the clown in his civilian clothes, the boy refuses to believe that his visitor is indeed Boum-Boum. The clown goes away and returns shortly later in his clown’s clothes to the child’s intense delight. When the doctor calls, he finds the little boy in gales of laughter being entertained by Boum-Boum, who even succeeds in coaxing the child to start taking herbal drinks. Boum-Boum tells the doctor that his pranks are as good for the little boy as the doctor’s prescriptions. The clown returns to see the little boy every day until he is well again. When the family asks him how they could repay him, he requests their permission to call himself “acrobat-doctor” and “little François’s family doctor’ on his business card.

This story clearly struck a chord, not just in France but internationally, over the succeeding decades. Many luxury editions of the story with illustrations were published in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century. The story of Boum-Boum and the little sick boy was even told in a 1933 French song, “Le Clown et L’Enfant,” and as recently as 2014, a French writer using the penname Edmond Dantes published a new version online.5 Boum-Boum was in fact a real person: the most famous and inventive clown in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Paris, Geronimo Medrano (born Madrid 1849 – died Paris 1912). Unlike the other clowns of his day who could be somewhat terrifying, he was very approachable and child-friendly. His circus, le Cirque Medrano, which was immortalized in drawings by Toulouse Lautrec, still flourishes today and its website states that Boum-Boum is said to have cured a little sick boy with his tomfooleries.

The clowns in LPJ illustration are obviously in the entertainment mode and there is hope, and indeed evidence, that laughter brings healing in the face of suffering and sadness. Laughter is a wonder drug and has been shown to reduce pain by releasing endorphins and to boost the immune system by increasing T cells and lowering stress hormone levels.6 There has been a shift away from clowns as entertainment to their role as trained professionals who bring artistry to the interaction between the patient, family, and staff. Three key concepts associated with modern therapeutic clowning include: (i) empowerment, to provide children who are in a state of helplessness with a sense of control (ii) play and humor, to decrease the tension and anxiety during painful procedures, and (iii) improving communication between the children and their caregivers to create bonds and support which aid the healing process.4

Clowns have worked in hospitals since the time of Hippocrates, while the court jesters of the Middle Ages episodically visited hospitals, as did the Whirling Dervishes in Turkish hospitals. Clowns appear in the cultures of many North American First Nations peoples.4 Humor and laughter are simple ways of bringing compassion and humanity back into medicine and incorporate the arts back into the scientific mode of medicine. Clowns in hospitals may work in different models of care, but fundamentally, they can help health professionals reach beyond their vulnerabilities and bring simplicity, joy, and compassion back into their daily interactions with both children and adults in today’s complex health systems.

References

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Le_Petit_Journal

- http://www.victorianweb.org/art/architecture/hospitals/1.html

- Markel H. When Hospitals Kept Children From Parents. The New York Times. January 1, 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/01/health/01visi.html?pagewanted=print&_r=0

- Alsop-Shields L1, Mohay H. John Bowlby and James Robertson: theorists, scientists and crusaders for improvements in the care of children in hospital. J Adv Nurs. 2001;35(1):50-8

- Dantes E. Boum-Boum ou le vrai visage des clowns. http://short-edition.com/auteur/edmond-dantes

- McGhee P. Humor: The Lighter Path to Resilience and Health. Bloomington, IN, 2010.

C. ANTHONY RYAN, MB, MD, FRCPI, is a consultant neonatologist in the Department of Neonatology, Cork University Maternity Hospital, Cork, Ireland and an associate professor in the Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, Brookfield College of Medicine and Health, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland

MA, PhD, is Emeritus Professor of French at the College of Arts, Celtic Studies and Social Sciences, and former Vice-President of Teaching and Learning, at University College Cork, Cork, Ireland.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 7, Issue 3 – Summer 2015

Leave a Reply