James Smith

United Kingdom

Author’s note

Any attempt to truly understand the impact of humanitarian crises on individual lives, particularly when perpetuated over the course of many years, may feel like an ever-receding ambition for those invested in humanitarian response. This is further complicated by sectoral advocacy strategies and programmes that speak of aggregate populations, and of collective problems.

Recognising the complex and problematic nature of speaking “for” others, with my own positionality and particular experiences, there is still perhaps a moral obligation of sorts to recount events that would not otherwise be remembered within a wider social circle. With this in mind, I have attempted to capture a fraction of the complexity of the provision of medical care in a remote hospital, in a chronically conflict-affected country in East Africa, by focusing not on numbers, but on individual encounters, and the minute details that shaped those interactions.

***

|

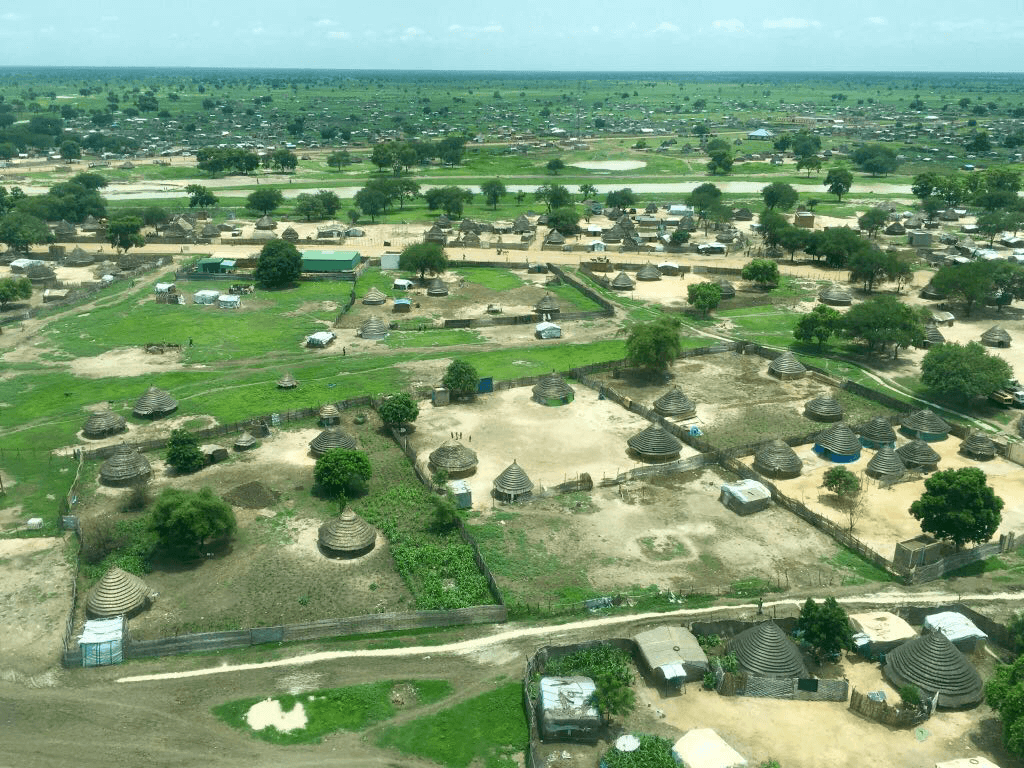

| Photo by Amy Neilson |

It was rarely a good sign to see the green partition by a patient’s bedside. Seldom static long enough to gather dust, it could otherwise be found against a rear wall in our rather disingenuously titled Close Observation Unit, from where it served ten beds and an additional thirty in the neighbouring inpatient department.

Attached to its heavy white frame were three bright green cotton curtains that formed a loose barrier against inquisitive eyes, offering the illusion of privacy for those contained inside. With the exception of those infrequent occasions that a procedure was performed on the ward, the presence of the partition meant only one of two things: someone had died, or was dying. The caretakers of patients knew this well, such that it was often only once the partition had been lifted from the wall that the gravity of the situation began to bear down on those present at the bedside. These moments were painful reminders of the complex ways in which meaning is conferred upon objects when words fail us.

There was a solemnity to this ritual that became too familiar in too short a space of time. Two people would carry the partition from one side of the ward to the other, while others tied sheets from the cord lattice that hung from the ceiling. This process was so time consuming that the pace was rarely able to match the frantic urgency of a resuscitation. In our haste to do something, attention to patient privacy was often an afterthought, prompted by the slow realisation that our attempt at resuscitation was failing, that there was nothing more that we could do but accept the worst.

‘We did everything we could …’. These words would often pass from doctor to bereaved relative, but rarely could they be delivered with conviction. It may be true that we did everything we could at that particular moment in time, in this particular hospital, but the words nevertheless carry an emptiness: spoken too many times without due consideration afforded to their meaning.

‘We did everything we could … but we didn’t have access to other forms of treatment, we weren’t even sure of the diagnosis … If we had better diagnostics, if the unit was better staffed, and if we had been able to ventilate …’

Following a series of unsuccessful resuscitations, the team convened to determine how best to allocate our time in the hospital. Ward cover was reorganised in the hope that we could prevent the sick patients from becoming any sicker. We simply did not have the capacity to continue to practise our crude form of intensive care, and so were pressed to choose between fragile neonates and a growing cohort of malnourished children; more responsive care in the emergency room or some form of continuity in the overflowing inpatient department; and a robust process of triage and community referral or a regular presence in the Observation Unit. Most medical professionals will acknowledge that it is almost impossible to make these difficult choices, and so it was with us.

The days became longer as the ward rounds finished later, consultations regularly interrupted by the radio announcing another harried request:

‘We’ve lost power in the Observation Unit and we had three children on oxygen …’

‘The diabetic woman has come for her insulin but the meter is reading high again …’

‘Can you come to triage? We have an unconscious patient sent from the clinic …’

With each encounter we would attempt to push back against the limits placed on our ability to deliver quality healthcare. On this particular day, like much of the last three months, malaria would successfully test those limits, prompting both solemn respect and intense loathing from amongst the team.

Despite four days of malaria treatment, the drugs were not working for this patient the way they usually do. There must have been something else. In these uncertain moments, I would often turn to a handbook. One in particular claimed to be essential reading for medical professionals working with tropical diseases. How peculiar the way that some phrases, so seeped in the dark history of colonialism, cling on in modern parlance. Diseases that are tropical to whom? Certainly not to these patients, nor to the national staff who have chosen to study and practise here. To this community, this is simply another day to bear witness to the continuous struggle between health and illness.

Nevertheless, our library was limited and I was pressed to look beyond the turn of phrase. Chapter One: Management of the Sick Child. Fingerprints had muddied the pages. I wondered if the same sense of panic had gripped the doctors who preceded me. My eyes scanned the text, but what could be done on reaching the section that read, ‘seek specialist input’, when there was no such specialist to be consulted? At least not this time. Not in time for this patient.

I might have called out to one of my colleagues, but on this day they were occupied on the other side of the hospital with a hypoxic newborn, leaving the nurse and myself: tired but nevertheless determined.

So it was that I unexpectedly found you behind the green partition.

Your mother and aunt became familiar to the team in the short time that you were with us. Each morning they would join us as we dosed the anti-malarials in which we had placed so much hope. It was your mother who accompanied you as you were transferred into the Observation Unit during the night, and your mother who sat by your side as we lifted the green partition from the wall and placed it at the end of the bed the following morning.

It was malaria that brought you to us, but far more than malaria that would take you away. The high prevalence of malaria here – so easily preventable, and often so easily treatable – is symptomatic of a series of systemic failures of which we bear witness, but that we have nevertheless chosen to overlook. Consider the predictability of the annual ‘hunger gap’ and the following ‘malaria season’. As the rains coax the maize crops, so follow the mosquitoes, and the yearly cycle continues. ‘A training ground’, was the way one person described your country. How little value those words placed in you. Complex lives and histories reduced to a place for Eurocentric humanitarian organisations to upskill their latest employees. The place where many medical professionals experience the nebulous discipline that is Humanitarian Medicine for the first time.

I found myself mumbling some empty platitude to your mother, knowing perfectly well that there was nothing about this situation that was remotely ‘ok’. The radio sounded from across the room: ‘We have a pregnant woman … labour for two hours … getting tired’. As I started to leave, I noticed the relative of a child in the neighbouring bed watching through a gap between the curtains. It seems that at some point we are all witness to the fragility of life, and the sheer injustice of death. I am struck that this injustice, hidden behind the green partition, and witnessed by so few, must not be met by silence: and so I will continue to remember you and your mother, the faded floral pattern of her dress, and the resigned familiarity with which the nurse removed the lines and tubes that we had hoped would bring you back to us. It should not have to be like this.

JAMES SMITH, MMBS, MSc, is a humanitarian researcher and medical doctor living in the United Kingdom.

Leave a Reply