Justin Shea

Ontario, Canada

|

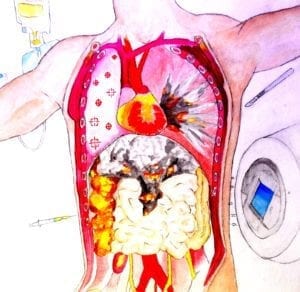

| The Battlefield of Cancer Treatment. Private Collection by Timamit, Mar 13, 2017. |

Ever since Richard Nixon declared war on cancer in 1971, the public has been convinced that the only way to deal with the disease is through combat1. But after forty years with destructive remedies such as chemo and immunological therapy failing to guarantee permanent remission, could it be possible that the medical field’s approach to fighting cancer is misguided? If this clash were applied to human conflict, for example, no rational military officer would resort to the strategies and tactics currently used in conventional cancer treatment2. It is therefore only appropriate that these strategies and tactics be assessed as if being employed in actual combat1. Unfortunately, when using the principles of an established military text like Sun Tzu’s The Art of War to analyze what kind of enemy cancer is and what current treatments actually achieve,, one can understand why the present course of humanity’s war on cancer is destined for ruin.

“Sizing up opponents to determine victory…is the proper course of action for military leaders.” – Sun Tzu2

A fundamental concept in war is knowing your enemy2. Doing so allows for greater understanding of an opponent’s characteristics, making it easier to uncover weaknesses and act on them2. By definition, cancer is a collection of unrepaired genetic mutations typically compounded over a period of time3. What makes the disease so difficult to resist are the hallmarks and enabling factors that promote its tenacious survival: its self-sustaining proliferative signaling; insensitivity to growth suppressors; resisting cell death; limitless replicative potential; inducing/sustaining angiogenesis; activating tissue invasion and metastasis; genomic instability and mutation; tumor-promoting inflammation; reprogramming of energy metabolism; avoiding immune destruction; and the recruitment of normal cells for survival3. If these behaviors described humans instead of cancer cells, the most appropriate equivalent would be a terrorist organization4-6. According to Canadian, UK, and US laws, acts such as unwarranted autonomous/constant growth in numbers; eluding/ignoring local authorities; opposing sanctioned military forces intent on their eradication; possessing an irrepressible philosophy that is pleasing to disturbed minds; finding/creating independent ways to spread their influence; broadening their scope to the global level and becoming flexible enough to adapt/disappear into foreign environments; indoctrinating those susceptible to the influence of disparate ideology; manipulating laws/philanthropic endeavors for self gain; disrupting sanctioned supply lines to fuel their agenda; and recruiting/intimidating civilians to bolster their survival all constitute a terrorist group’s standard operating procedure4-9. Since cancer cells originate from cells indigenous to the body, it is reasonable to classify cancer as a domestic terrorist.

“If you do not first think about the calamities of danger and destruction, you will not be able to reap any advantage.” – Du You2

This observation should be cause for concern, as the strategies for the effective neutralization of domestic terrorism fall more under the realm of law enforcement rather than the armed forces2,6,10. This distinction is crucial, considering that the devastation brought on by all-out military action inevitably leads to mass casualties, collateral damage of civilian sectors, and possibilities of future uprising and mutiny11,12. These consequences in destructive cancer therapies are often responsible for the treatments’ harsh side effects and therapeutic failures3,13-19.

Thus, in spite of their improved precision, modern surgical techniques indiscriminately destroy both healthy and cancerous cells 20. Since the devastation is localized, surgery’s battlefield equivalent would most resemble an airstrike. The issue with airstrikes is that they fill a particular niche in combat: unable to distinguish innocent hostages from enemy combatants and may become ineffective if terrorists are buried too deeply or have spread too far apart. Even when deployed perfectly, an airstrike’s destructive capabilities must be regulated. Destroy too little and terrorist cells will survive20,21. Destroy too much and the local populace will suffer19,20. Radiation treatments are also like airstrikes, though they often carry lasting collateral effects . Like airstrikes in real life, neither technique is expected to fully cure local terrorism without additional reinforcement.

“Confront [a desperate enemy] with annihilation, and they will survive.” – Sun Tzu2

The battlefield equivalent of chemotherapy is a nuclear bomb. Despite repeated attempts to restrict these chemicals to affected cells, chemotherapy freely invades all manner of tissues, leading to many side effects22. Perhaps its most frightening repercussion is its potential to create secondary cancers23. This phenomenon can occur through apoptosis-induced proliferation, where cells surrounding the target cell experience a compensatory boost in reproduction to recuperate from the damage13. Cancer takes full advantage of this boost and proliferates wildly13. Other types of cell death such as necrosis experience comparable compensatory growth, facilitating further tissue metastasis24. Although other modes of destructive cancer therapies are not immune to these compensatory effects, the act of targeting cancer for annihilation is exactly what causes it to resist death and regrow vigorously1,2,13. There are two good reasons why even the most fanatical war general would hesitate to use nuclear weapons: concern for whether the planetary body can recover afterwards and fear of whether the body’s survivors will continue to uphold social order.

“The pursuit of certain victory [is] by knowing when to act and when not to act.” – Sun Tzu2

The promise immunotherapy brings is specific targeting of cancer cells for destruction while minimizing harm to normal tissue – much like the perfect special forces soldier25. But the heavy price for harnessing the immune system to battle cancer is that the scope of its sensitivity is artificially widened to recognize these cells14,25,26. Should the discernible traits share any similarities with normal somatic cells, this could be the battlefield equivalent of ordering soldiers to fire on anyone having red hair simply because it is distinct. Unlike Navy SEALs, immune cells lack the autonomy to re-interpret their programming, causing an ever-increasing risk of normal cell casualties as treatment continues14,17. Even after treatment concludes, no currently recognized medical therapy can fully reverse this independently-adaptive Pandora’s box14,15,27,28. As with any manipulation of the immune system, the fear of autoimmunity looms overhead14-18. Since autoimmune conditions are progressive without actual cures, treatments usually focus on immune suppression, inadvertently increasing reliance on anti-virals and antibiotics29. With antibiotic stewardship failing to prevent rising micro-organism resistance, patients cured of cancer may live only to die from untreatable infection30,31. Immunocompromised patients are also more susceptible to new cancerous growths than immunocompetent patients, which creates a potential treatment paradox3,14.

Recently, genetic reprogramming through the CRISPR-Cas 9 complex has gained popularity as a novel treatment option27,28. Despite the excitement, the technique is still in its infancy and confined to reprogramming immune cell genetics to target cancer cells27,28,32. Although promising, the current fashion in which CRISPRs are employed restricts it to an immunotherapy paradigm14,32.

“Arm[arment]s are tools of ill omen – to employ them for an extended period of time will bring about calamity.” – Du You2

According to historians, Sun Tzu wrote The Art of War with the intent to minimize conflict because he understood the costs of prolonged campaigns2. Possessing strategy means the difference between fighting a couple weeks’ skirmish or suffering years of siege, but what often shortens combat is the tactical acumen of the field commanders2. Cancer treatments’ biggest weakness is that the moment they enter the body, all rational judgment disappears. Surgeons and radiologists cannot instinctively separate malignant, benign or normal cells unless there are obvious physical differences; chemotherapy cannot control its dissemination; and as specific as immunological therapy is, in its current state the treatment cannot truly distinguish between a genetically normal cell and a cancerous one14-18,20, 22, 33. This means every available cancer therapy is slaughtering on instinct without awareness of their actions. Without mindfulness, cancer treatments are nothing more than blunt weapons. Winning a war takes more than just the deployment of weaponry2.

“The important thing in a military operation is victory, not persistence.” – Sun Tzu2

As the elderly population increases over the next few decades, a surge in cancer cases is expected to occur. But since frailty increases with age, patients’ tolerance to destructive treatments and side effects tends to diminish, especially if they have used such remedies before. If unleashing weapons into patients – that may or may not rid them of their disease – is the best solution available, perhaps cancer researchers are correct in that the war on cancer requires strategic reassessment1. This reanalysis, however, should not preclude shifting the goals of cancer treatment itself. Cancer is an adaptive, organic enemy whose sole purpose is survival. Continued use of this annihilation strategy is almost like playing cancer’s game – a game in which cancer is infinitely better at playing. As mentioned previously, the effective neutralization of terrorism falls under the realm of law enforcement2,6,10. Outside of the death penalty, the ultimate goal of law enforcement is to rehabilitate prisoners – that is why jails are often referred to as correctional facilities. If rehab works, released prisoners often rejoin society as functional citizens, casting aside their destructive tendencies. Perhaps what is required for an actual cure for cancer is the rehabilitation of cancer cells, genetically reverting them to their pre-malignant state. Restoring the ‘brain’ of the cell, should curtail the impact of epigenetic changes, allowing malignant cells to become a constructive part of the united body once more.

References

- Hanahan D. Rethinking the war on cancer. Lancet. 2014;383(9916):558-563. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62226-6.

- Sun T, Cleary T. The Art of War: Complete Text and Commentaries. 1st ed. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications; 2003.

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646-74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013.

- Borum R. Understanding Terrorist Psychology. Scholar Commons University of South Florida. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1575&context=mhlp_facpub. Published January 2010. Accessed January 14th 2017.

- CIA. Terrorism FAQs. CIA. https://www.cia.gov/news-information/cia-the-war-on-terrorism/terrorism-faqs.html. Published April 6th 2007. Updated April 19th 2013. Accessed January 14th 2017.

- Majoran A. The Illusion of War: Is Terrorism a Criminal Act or an Act of War? Mackenzie Institute. http://mackenzieinstitute.com/illusion-war-terrorism-criminal-act-act-war/. Published July 31st 2014. Updated July 31st 2014. Accessed January 14th 2017.

- Government of Canada, Dept. of Justice. Definitions of Terrorism and the Canadian Context. Government of Canada, Dept. of Justice. http://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/victim/rr09_6/p3.html. Updated January 7th 2015. Accessed January 14th 2017.

- Government of Great Britain, Ministry of Justice. British Terrorism Act 2006. Government of Great Britain, Ministry of Justice. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/11/contents. Updated December 5th 2016. Accessed January 14th 2017.

- US Government. Patriot Act. US Government Publishing Office. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-107hr3162enr/pdf/BILLS-107hr3162enr.pdf. Published January 3rd 2001. Accessed January 14th 2017.

- Essig CG. Terrorism: Criminal Act of Act of War? Implications for National Security in the 21st Century. US Army. https://www.google.ca/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwjRx8eHyfXQAhVC-GMKHaKCBWIQFgglMAE&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.hsdl.org%2F%3Fview%26did%3D438594&usg=

AFQjCNHChBpE87ooxlB52BVtEigt20cYkg&sig2=_932klvKHiTyRzJ9lz8U4g. Published March 27th 2001. Accessed January 14th 2017. - Henig R. Versailles and Peacemaking. British Broadcasting Corporation. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/wwone/versailles_01.shtml. Updated March 10th 2011. Accessed January 14th 2017.

- British Broadcasting Corporation. Hitler’s rise to power. British Broadcasting Corporation. http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/gcsebitesize/history/mwh/germany/hitlerpowerrev2.shtml/. Accessed January 14th 2017.

- Ryoo HD, Bergmann A. The role of apoptosis-induced proliferation for regeneration and cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4(8):a008797.

- Baumeister SH, Freeman GJ, Dranoff G, Sharpe AH. Coinhibitory Pathways in Immunotherapy for Cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2016;34:539-73. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112049.

- Haanen JB, Thienen Hv, Blank CU. Toxicity patterns with immunomodulating antibodies and their combinations. Semin Oncol. 2015;42(3):423-8. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2015.02.011.

- Abbi KK, Rizvi SM, Sivik J, Thyagarajan S, Loughran T, Drabick JJ. Guillain-Barré syndrome after use of alemtuzumab (Campath) in a patient with T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia: a case report and review of the literature. Leuk Res. 2010;34(7):e154-6. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2010.02.036.

- Rossignol J, Michallet AS, Oberic L, Picard M, Garon A, Willekens C et al. Rituximab-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone combination in the management of autoimmune cytopenias associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2011 Mar;25(3):473-8. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.278.

- Westdorp H, Sköld AE, Snijer BA, Franik S, Mulder SF, Major PP et al. Immunotherapy for prostate cancer: lessons from responses to tumor-associated antigens. Front Immunol. 2014;5:191. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00191.

- Cancer.net. Side Effects of Surgery. Cancer.net. http://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/how-cancer-treated/surgery/side-effects-surgery. Accessed January 14th 2017.

- Mukherjee S. The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 2010.

- Cancer.net. What is Cancer Surgery? Cancer.net. http://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/how-cancer-treated/surgery/what-cancer-surgery. Accessed January 14th 2017.

- Cancer.net. Side Effects of Chemotherapy. Cancer.net. http://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/how-cancer-treated/chemotherapy/side-effects-chemotherapy. Accessed January 14th 2017.

- Cancer.net. Long-Term Side Effects of Cancer Treatment. Cancer.net. http://www.cancer.net/survivorship/long-term-side-effects-cancer-treatment. Accessed January 14th 2017.

- Ricci MS, Zong WX. Chemotherapeutic approaches for targeting cell death pathways. Oncologist. 2006 Apr;11(4):342-57.

- Cancer.gov. Immunotherapy. Cancer.gov. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types/immunotherapy. Published April 29th 2015. Accessed January 14th 2017.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Immunotherapy. American Cancer Society. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003013-pdf.pdf. Published July 23rd 2015. Updated August 8th 2016. Accessed January 14th 2017.

- Kaiser J. The gene editor CRISPR won’t fully fix sick people anytime soon. Here’s why. Science Magazine. http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/05/gene-editor-crispr-won-t-fully-fix-sick-people-anytime-soon-here-s-why. Published May 3rd 2016. Accessed January 14th 2017.

- Ledford H. CRISPR, the disruptor. Nature. http://www.nature.com/news/crispr-the-disruptor-1.17673. Published June 8th 2015. Accessed January 14th 2017.

- Mayo Clinic Staff. Prednisone and other corticosteroids. Mayo Clinic. http://www.mayoclinic.org/steroids/art-20045692. Published November 26th 2015. Accessed January 14th 2017.

- US Center for Disease Control. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013. US Center for Disease Control. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf. Published 2013. Updated July 17th 2014. Accessed January 14th 2017.

- Fukunaga BT, Sumida WK, Taira DA, Davis JW, Seto TB. Hospital-Acquired Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia Related to Medicare Antibiotic Prescriptions: A State-Level Analysis. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2016;75(10):303-309.

- Su S, Hu B, Shao J, Shen B, Du J, Du Y et al. CRISPR-Cas9 mediated efficient PD-1 disruption on human primary T cells from cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2016; 6: 20070. doi: 10.1038/srep20070.

- Cancer.gov. Chemotherapy. Cancer.gov. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types/chemotherapy. Published April 29th 2015. Accessed January 14th 2017.

JUSTIN DEAN SHEA, BMSc, BSc Pharm, is a graduate of Western University’s Bachelor of Medical Science and the University of Waterloo’s Pharmacy programs. He has a passionate focus on cancer, which claimed his grandparents before he got to know them, and will at some point affect roughly half the world’s population. A student of Legacy Shorin Ryu Karate Jutsu for ten years, Justin is constantly reassessing the use of destructive medical therapies through martial philosophies. He has recently published a science fiction novel, Destructive Salvation, centered around theories of a non-destructive, universal cure for cancer, available now.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 10, Issue 1 – Winter 2018

Spring 2017 | Sections | Science

Leave a Reply